A Democratic program for working class men

An outline for a pro-worker economic policy

Statement of the problem

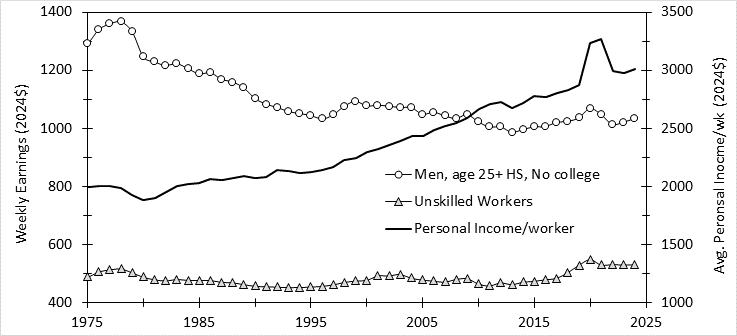

I believe a fundamental cause of the discontent among working class is shown in Figure 1. It shows three measures of income over time. The first is real personal income divided by total employed people. It represents total income (adjusted for inflation) received by individuals through paid employment, business income, rents, and other investment income divided by total employed persons. It provides a measure of the average income received by participants in the economy. It shows a 50% rise over the last fifty years, the results of economic growth. Also shown in the figure are two measures of working-class earnings. One is the real unskilled wage index, which shows earnings obtained from entry-level employment available to all workers regardless of education. It has shown a modest rise of 5-8% over the last half century. Finally, I show earnings of men aged 25 or older who have a high school education, but no college. This group has shown an absolute decline in real wages of about 20% since 1975.

Figure 1. Earnings for Men age 25+ with a HS degree and no college 1979-present (pre-1979 data extrapolated back using unskilled wage index). Also shown are personal income per worker and unskilled wages The data was adjusted for inflation using the CPI.

The difference between the wages earned by high school grads over the age of 25 and unskilled workers provides a measure of the room for advancement for working class men who enter the work force right out of high school, where most will earn the unskilled wage and advance to higher-paid jobs over time.

The success sequence consists of three steps through which a young person can avoid poverty and make a go of life:

Finish high school.

Get a full-time job once you finish school.

Get married before you have children.

Achieving the first two of these at age 18 puts a young man into the unskilled category, but with a HS diploma. Seven years later, he will fall into the higher-earning age 25+ category. The benefit of this progression in the past was greater than it is today. In 1979, experienced working-class men earned 165% more than unskilled workers, while today the premium has fallen to 95%. An 18-year-old working-class man in 1979 had better future income prospects than his counterpart today. A consequence of his fact shows up in marriage statistics, which shows declining marriage rates for men born after 1955, that is, men who were of typical marriage age in the late 1970’s. After this time, future earnings prospects declined as did marriage rates.

A second, related source of worker discontent is illustrated by Figure 2, which shows how earnings relative to personal income for different classes of income recipients have changed since 1960. Three classes of income recipients, corporate executives, investors, and physicians saw gains relative to personal income. That is, they saw a world that grew more affordable with time. Since much of investor income is reinvested, the expected result of from the doubling of investor income shown in Figure 2 has been rising asset prices such as higher home prices. Rising executive incomes translate into rising administrator cost. This and administrative bloat in universities and colleges play a major role the cost of higher education outstripping inflation. Rising costs of administrators, physicians and quality gains in medicine have each played a role in soaring health care costs, which has made life less affordable for working people.

Figure 2. Income for various groups relative to average personal income.

Executive income from Wells 2011, Frydman and Saks 2008 and the Federal Reserve. Physician compensation data sourced from Dahle, Langenbrunner et al, Crane, and Leigh et al.

Rising living standards, which is captured by the personal income measure, provides a useful ruler for determining the winners and losers of economic developments since the seventies. As Figure 2 shows, the working class have fallen into the loser category, with mature working class men showing a 50% decline in their status relative to the other classes. This group, and the young working class men who see this group as their future form one of the core constituencies for the MAGA movement.

Why the MAGA solution is misguided

Back in the sixties and seventies, a young guy not interested in college would try to get a job in industry, which tended to pay a lot more than fast food or other unskilled service positions. This has led people to believe that the reason working class people had it better back in the day was because of “good manufacturing jobs.” This idea is supported by the belief that manufacturing jobs paid more money because manufacturing is a highly-productive economic sector. The idea is wages are based on the productivity of the worker. If this were true than we would expect wages for production workers to track productivity. On the other hand, wages for unskilled service workers relative to productivity would be expected to decline over time. The reality is both have declined at the same rate. Another piece of evidence is Figure 3 which shows a plot of annual productivity growth and investor income as a percent of GDP. Economic productivity has declined over the past 75 years while investor return has risen. In fact. there seems to be almost an inverse relation between productivity growth (i.e. what investment is trying to achieve) and the compensation awarded to that investment. This clearly shows that compensation is uncoupled from productivity. As Figure 2 shows, executives today earn far more than their more productive counterparts in the past.

Figure 3. Annual productivity growth and investor income as a percent of GDP.

Productivity is quarterly data smoothed with exponential average with a = 0.97.

So where does this notion of a relation between income and productivity come from? It is true in the aggregate, as I discussed here. Productivity is simply GDP divided by hours worked. Since income is necessarily less than GDP, income per hour worked (wage) must be some fraction f of productivity for all workers. Aggregate income is just personal income which makes up a fairly constant fraction of output as shown in this figure. Thus, by normalizing incomes to personal income as I did in Figure 2, I control for the effects of productivity changes. Thus, productivity is not an explanation for the trends shown in that figure. The same thing is true for executives.

There is nothing magical about manufacturing jobs. Bringing them back through tariffs or industrial policy will not improve the fortunes of working-class men. There are other reasons for bringing back manufacturing, such as maintaining military capability, for which a tariff policy might make sense. But the idea that slapping tariffs on countries to which America has outsourced jobs will bring back the high paying jobs that were outsourced is nonsense. The amount of money a job pays (relative to personal income) depends on both economic (supply and demand) and cultural factors, and less on the kind of job. One might note that highly skilled workers such an elite software engineers command high-salaries. But this is because such individuals are in relatively short supply relative to the demand for them. I personally know a very talented classical musician, the product of years of investment in developing that talent, whose compensation is scarcely above that of an unskilled worker, because of supply and demand.

What could work: return to SC culture and removal of restrictions to growth

I have previously written a great deal about how the policy that underlies shareholder primacy (SP) business culture produces worse results for the economy and working people by favoring the accumulation of shareholder value in lieu of real growth. I have suggested that a return to SC culture would lead to better economic growth and better results for ordinary people. The way this works is through three mechanisms. First corporate contributions to growing stock market capitalization are impeded by banning stock buybacks and raising taxes on dividends, These actions encourage retention of profits which can either be invested in enterprise or short-term debt instruments which typically provide a low return (about 1% real return over the 20th century1). In contrast, today a high-return alternative to investment in enterprise exists in the form of stock buybacks. Stock buybacks earn capital gains returns, which over the past 30 years have run at a 6.3% real return. Clearly there are a great many investments in enterprise that earn a return substantially greater than 1% but less than 6%, which would not be made today, but would be made were stock buybacks illegal.

The second mechanism is cultural, the effect of high marginal tax rates on very high incomes. Figure 4 shows a plot of executive income, adjusted to 2024 dollars using GDP per capita and the marginal tax rate corresponding to that income. The data show that executive monetary compensation fell as the marginal tax rate rose above ca. 60% during the 1940’s and rose when it fell below 60% in the 1980’s. Reduced monetary compensation in the post-war era was offset by generous non-cash fringe benefits so CEOs still lived very well. Limitations on money compensation and banned stock buybacks meant there was no way to incent executives to focus on shareholder value above all else, as called for by shareholder primacy culture. This mechanism uncouples executive motivation from a focus on shareholder value, while the ban on stock buybacks blocks easy ways to serve the goal of promoting shareholder value. Both select against shareholder primacy cultural elements in the process of cultural evolution, producing a business culture that more closely resembles stakeholder capitalism.

Figure 4. Executive money income and their marginal tax rates

The third mechanism is policy changes designed to make capital-intensive investments easier to pursue. One of these is low real interest rate, which requires a low inflation environment that in the past was produced by balanced government budgets. Another is the presence of strong leading sectors. Leading sectors are the collection of new industries that lead economic growth at a particular time. The environment over the last several decades reflects the current information economy leading sector. In my 2004 political cycles book I contrasted the growth prospects for the information economy compared to the mass market economy that powered the postwar boom:2

Many new [information economy] products have been introduced, but these often replace previous products rather than form a new type of spending. For example, personal transportation technology (cars) in the mass-market economy created a new source of revenue for businesses (and new employment opportunities). What was “replaced” by the auto was walking, which was free. Autos created a new category of household spending. New products like cell phones do not create a similar new category of spending. Their revenues, to some extent, come at the expense of older industries.

I echoed this idea in my post about why progress seems stalled and in comments about how investments in disruption mostly serve to generate financial rather than economic benefits. In my book I concluded that the information economy as of 2003 was only about a third the size of its mass market predecessor.3 I argued that to produce the sort of strong growth we had in the post-war era required a bigger new economy calling for “new leading sectors built around alternative energy sources (biomass, nuclear, solar, wind)”4 and health care.5

Since then, some of the developments I called for have happened. Solar energy has surpassed my wildest expectations, while biomass has been disappointing. I see solar energy more as a source for liquid fuels as a replacement for petroleum and less as a source of electric power. And there has been an unexpected (to me) new arrival: the fracking revolution that has tapped the vast shale oil and gas reserves in North America I read about during the 1970’s energy crisis.

But there has been a problem. New solar arrays are built, but cannot be rapidly connected to the grid because of difficulties in grid expansion. Wind turbine projects are blocked by objections from homeowners. Pipelines needed to transport new oil resources are blocked. And this is just the tip of the iceberg. Housing is not being constructed in some places at anywhere near the rate necessary to meet demand, leading in soaring prices. With the publication of Abundance there has been much discussion about the numerous restrictions on doing stuff. These are valid observations and reforms to zoning restrictions and ESH (environmental, safety and health) regulations that slow the rollout of new leading sectors are absolutely necessary.6

These do not address the business culture aspects of the issue, however. If you clear the path for building things, what gets built? Will it be business that grows the economy and affordable housing, or will it be business that builds “ziggurats of finance” and luxury housing? The approach suggested by progressives, to try to prevent development with adverse ESH effects often means no development at all. In contrast, even bad development had positive outcomes for ordinary people in an SC economy. For example, as late as the early 1990’s when my employer still operated under SC culture, one could hear workers refer to objectionable fermentation plant odors as “the smell of money.” I no longer heard this after mergers, layoffs, and outsourcing started happening, heralding the arrival of shareholder primacy.

ESH regulations were passed during a time when the effects of bad development had begun to show clear negative effects that were no longer acceptable to a middle-class nation. This development had helped transform a tenement-dwelling working class into middle-class homeowners, which was why New Deal progressives of the 1930’s through 1950’s were so supportive of development. Were regulatory laws eliminated, whether or not we would return to the bad old days of pollution and dangerous workplaces would depend on the business culture. Under SP culture, where the response to pollution is to offshore operations to places where ESH is not an issue, eliminating environmental laws might simply move the pollution here, particularly in a world of high tariffs. Progressives are leery of pro-development efforts under SP culture which could mean imposition of ESH costs on ordinary people for the sake of higher market capitalization.

Under SC culture, the community in which the plant operates is one of the stakeholders, in which case both the economic and ESH effects of the project can be taken into consideration. An SC economy that builds things, both imposes ESH costs and delivers economic benefits to ordinary Americans as compensation.

Dimson, E., P. Marsh, and M. Staunton. 2002. Triumph of the Optimists: 101 Years of Global Investment Returns. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Cycles in American Politics p 112.

Cycles in American Politics p117-118.

This requires a restructured healthcare industry, which I will discuss in a later post.

This is major issue beyond the scope of this post.

It benefits the investor class. Under shareholder primacy (SP), the economy builds "ziggurats of finance"

https://mikealexander.substack.com/p/ziggurats-of-finance

As Stafford Beer quipped, the purpose of a system is what it does. The purpose of the SP economy to create massive collections of financial value (i.e. the ziggurats) or in other words, asset bubbles. Bubbles can pop and give rise to financial crises.

https://mikealexander.substack.com/p/how-sp-culture-produces-financial

As I pointed out in the ziggurats post, building that monument involved extracting 3.2% of GDP (relative to the old SC system) from the peasantry (i.e. working and middle classes) and using it to construct the monument.

The resources used to build the ziggurat could have been used to produce economic growth. A quick back of the envelop calculation suggests the cost of monument building is about 0.8 points of GDP growth. The US would still be the most powerful country in the world had we chosen that path (as the Chinese are clearly doing).

This is why nations and empires fall. Their leaders choose with eyes wide open, the path towards decline. To build virtual monuments that don't even have corporeal reality rather than real national strength. Why do they do it? Well, most of that monument represent the cumulative surplus income of rich people. They don't NEED that income or it wouldn't be surplus. So they invest it, what else can you do with it. As for why this seek to build up their fortune, it is a form of social signaling moderated by capitalism

The naturalness with the idea of investing your extra money is the core of what capitalism is Before capitalism was invented this was not natural. Take the Italian Renaissance merchants. They did not invest in more ships, because it would drive down prices to the ruination of all. Rather they spent the surplus profits on patronage of the arts as a form of social signaling rather than capitalist who would invest the money instead, also for social signaling. The pre-capitalist merchant's choice gave us the Renaissance. OTOH the capitalist merchants gave us either the industrial revolution and modern prosperity (under SC) or ziggurats of finance (under SP).

Love it.

Stakeholder capitalism seems so obvious but Uncle Milt is sooooo addictive. He was wrong then, he is still wrong. But his theories and that idiotic Laffer curve is just so easy for the investor class to hear.