Some observations on the election

Working class Democratic weakness seems due more to economics than culture

Democrats lost because they do not have the dispensation

The issue Democrats face today is that Donald Trump, who tried to overturn the last election, which should have disqualified him for office, won a second term. That Democrats are unable to win handily against a figure like Trump shows a real shortfall with the party. As my last post showed, Democrats lost because they do not hold the dispensation and the sitting president was from their party and was not running. This situation has arisen ten times since 1828, seven times for Democrats and three times for Republicans. All ten lost.

In 1968 the Democrat president Johnson had enmeshed the country in a second unpopular war and opted not to run, yielding the White House to Republican candidate Nixon. The Democrats had created a forty-year period of rising wages that converted an impoverished working class into a prosperous middle class. The trend in real unskilled wage tells the story. This achievement made their dispensation unassailable. The power of the dispensation was demonstrated when corrupt Republican president Nixon resigned from office, while the far more corrupt and twice-impeached Republican president Trump went on to win another term. The first happened under a Democratic dispensation, while the second happened under a Republican dispensation. Clearly, corruption in the party holding the dispensation is tolerated, but not in the opposition.

Democrats threw away their dispensation through unforced errors. and in 1980 Republicans regained the dispensation they had lost in 1932. Now they win by default, only losing when they fuck up. In 1992 they had been in power for 12 years, and despite the end of inflation, they had failed to restore the wage growth of the past. Third party candidate Ross Perot, decrying their economic failure and blaming it on Republican fiscal irresponsibility, helped defeat incumbent George H. W. Bush in 1992. Democrat Bill Clinton responded to the Perot critique by not only balancing the budget but generating a surplus. Yet voters saw fit to reject the continuation of the Clinton success offered by his VP in exchange for the rehashed Reaganomics offered by Republican George W. Bush. Bush presided over 911, the failed Afghan and Iraq wars, and the crash of the economy setting up Democrat Barrack Obama for a comfortable victory in 2008, The Obama administration fixed things, served two terms and then was replaced by Trump in 2016, who promised to take a hammer to things. In 2020 a pandemic broke out, the response was botched and voters put Democrats back in. They patched things up and come 2024, times were good. President Biden withdrew from the race for health reasons, so Republicans won. When Republicans next screw up, Democrats will be put back into power, probably in 2028.

The reason why Republican administrations screw up is because their dispensation cannot address most of the problems we face today, such as working-class discontent with the modern two-track economy. In this economy, one group of Americans have jobs in which they create real stuff or perform concrete services and another whose jobs involve intangibles, what Robert Reich calls symbolic analysts. Reich notes

while the fifth of the population composed of symbolic analysts is doing better and better, the four-fifths comprising production and in-service workers is doing worse and worse. Moreover, as the gap between the two groups widens, the symbolic analysts are in effect seceding from the nation by withdrawing into their own enclaves…

These enclaves are increasingly cultural, with the two groups coming to live in different moral universes. As parents and teachers urged more young people to go to college in order to become symbolic analysts and reap the rewards that come from this economic role, they picked up their culture, but did not necessarily gain the economic benefits, falling economically into the working class while retaining the symbolic analyst culture. On the other hand, many who work in the tangible economy, in the trades or as small business owners, earn far above a working-class income, but continue to have a cultural affinity with tangible economy workers who do earn a working-class income. Hence, we have a politics reflecting a working class versus professional class divide based on both economic (nature of work) and cultural belief elements.

Working class voter have valid reasons for displeasure with the Biden economy.

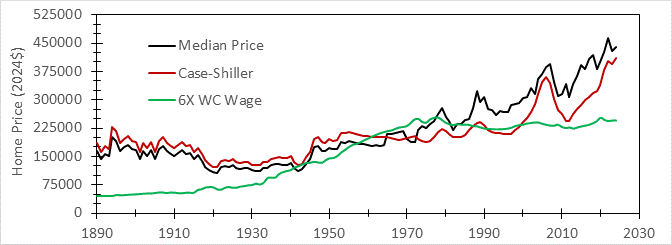

As the rising costs of housing, health care, and education continue to outstrip wage growth, economic frustration sets in. Consider housing. All of the inputs into a house are tangible things produced by tangible-economy workers. Because labor is a major cost in construction, the cost of houses should track wage growth for tangible workers. And for a long time, this was indeed the case. Figure 1 shows median and quality-adjusted prices for homes since 1890. The Case-Shiller index (in red) is designed to show home price inflation over time, rather than the actual price increases that reflect both inflation and increases in quality such as larger size. The data are adjusted for consumer price inflation using the CPI, so what is shown by the red line is home price inflation in excess of general inflation that is not due to quality improvements. The figure shows that while real home prices moved steadily upwards since 1945, home price inflation was about the same as CPI inflation until the late 1990’s.

Figure 1. Real median home price and Case-Shiller index compared to working class (WC) wages

Since then, prices have risen without a corresponding increase in quality. Some argue this reflects issues with zoning, but the same thing happened with equity prices. This figure shows that both the Case-Shiller index and stock prices (given in terms of my valuation parameter P/R) rose in the late 1990’s and for the same reason, rising demand for assets by an increasingly wealthy upper class. Of particular interest is the green line in Figure 1 showing a multiple of the working class (WC) wage. WC wage is the average of usual weekly wages for high school dropouts and high school graduates. These values were extrapolated back before 2000 with an unskilled wage index and adjusted for inflation with the CPI. This line shows that before WW II, owning one’s home was out of the question for working class people. After WW II the situation for working class people improved dramatically as they increasingly were able to afford to own their own homes, a traditional marker of middle-class status. America became a middle-class nation in the decades after the war. Though real home prices rose, wages more than kept up with them. This ended in the late 1970’s. Homeownership reached a plateau in 1981. A short-term increase began in the 1990’s encouraged by Clinton administration programs designed to make neoliberalism work for those left out. It ended with the post-2005 real estate bust.

A similar story could be told about health care or education, prices for both have risen faster than wages. These purchases tend to be subsidized through government welfare programs that serve to blunt the effects of price increases. The biggest difference in the two party’s economic offerings concern welfare programs like these. Conservatives note that provision of free goods diminishes the motivation for work, while liberals believe all Americans should be able to have a decent standard of living if they work fulltime, and advocate for government assistance to bridge the gap between the standard and what the economy can provide.

What working class people would prefer an economy that allowed a decent lifestyle to be achieved from earnings from jobs providing tangible goods and services that are clearly in demand—as it was in the past. Democrats, who until relatively recently were seen as the party of the working class, have not tried to deliver such an economy as they used to. They believe this is no longer possible. This belief is an example of the operation of the Reagan dispensation, which serves to sustain neoliberal economic policy. As long as Democrats believe this, they are playing on Republican turf and will be unable to win elections like 2000, 2016 or 2024 no matter who they run or what kind of message they craft.

Voters offered cultural stances or welfare in lieu of an economy that works for them.

Neither party’s economic programs offer much to working class voters. Republicans offer goodies for the rich and investor class, mostly in the form of tax cuts. Democrats offer means-tested programs that largely benefit lower income people. The beneficiaries of Democratic programs are sometimes seen as people not pulling their weight by their peers, while the much more lavishly rewarded beneficiaries of Republican policy are largely invisible. Perceiving little difference in benefits to them from each party’s policies, working and middle-class voters pay more attention to the party’s non-economic offerings, mostly cultural stances or symbolism. Prior to the onset of the creedal passion period around 2013, Democratic cultural offerings mostly served to boost support among educated voters, who were put off by the conservative shift in Republican social attitudes intended to appeal to former Democrats driven away by passage of the 1960’s civil rights laws. They coupled this with welfare programs to offer something to their lower income voters.

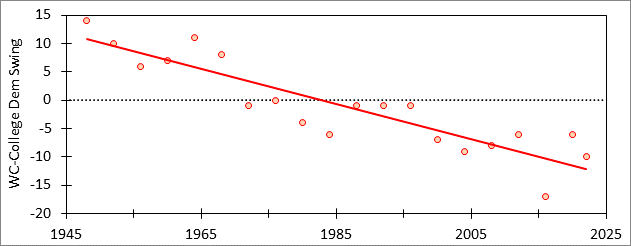

Figure 2 shows a plot of the Democratic vote percentage from noncollege voters (a proxy for working class) minus college-educated voters (professionals) over time. Up through 1968 working class voters voted significantly more Democratic than professionals. After this a new balance arose. For the next thirty years, when Reagan was not running, working class and professionals showed roughly equal support for Democrats. Since the beginning of the century, working class voters have favored Republicans by 5-10 points, except when Trump was running, when it was closer to 20%.

Figure 2. Democratic vote from non-college less college voters over 1948-2022.

Piketty Figure 3.3a

Some observers have suggested that it was an excess of enthusiasm for social justice issues (“wokeness”) that led to the broadening of this gap under Trump. Trump positioned himself as a champion of conservative cultural aspirations. For example, he promised to appoint anti-abortion judges in 2016—and delivered—abortion is now banned or severely restricted in much of red America. In 2024 he ran a virulently anti-woke campaign.

This enthusiasm is a manifestation of the current creedal passion period (CPP), which is now in decline and I expect it to end in a few years. I looked at the voting behavior during the last CPP (1963-77) and the current one (2013-27) and found no evidence of CPP effects on working class Democratic support. Working class support for Democrats was strong in 1968, the peak year for the past CPP. Support was also strong (compared to the surrounding period) in 2020, the peak year for the present CPP. Though Republicans have campaigned intensely on these issues, how much of a role they have played is unclear. One would think that an anti-woke cultural stance would have been more effective in 2020 when American cities were aflame with woke-inspired political turmoil than in 2024 when the electorally most potent cultural issue (as revealed by the 2022 election results) was abortion, which works against the Republicans.

Economic reasons for decline in working class Democrat vote make more sense.

What makes more sense to me is working class support for Democrats has diminished in tandem with diminished Democratic interest in enacting policy creating an economy that works for them. The original Democratic working-class coalition was created by Franklin Roosevelt by creating a tangible economic benefit to working class voters and informing them directly about what he was doing as it was happening. By doing this Democrats were able to win the 1934 election and set a new dispensation around which politics would revolve, as Reagan would later do. The policies (high tax rates, pro-labor bias, and economic stimulus) the New Dealers implemented during the Depression and WW II created the economy that lifted the working class from tenement dwellers to homeowners as shown in Figure 1. Those who came of age under Roosevelt leaned Democratic for the rest of their days.

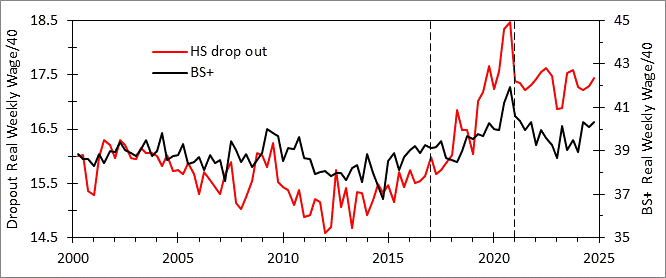

As for the 2024 election, Figure 3 shows a plot of real weekly wages for high school dropouts versus college grads, The scales used for each were set to reflect the same percentage increase in order to make comparison meaningful. It is clear that wages for those with the least education are considerably more volatile than those for the college educated. What is also apparent is the sharp rise in wages during Trump’s first term (demarked by the dashed lines). This rise is contrasted with little rise during the Biden administration. Election commentators like to say that it was inflation that doomed the Democrats and that working class voters failed to understand that high inflation was over. Working people are not stupid, had their wages continued to rise in real terms as they did after the 1946-47 outbreak of inflation, more of them would have voted Democratic as they had in 2020. But they did not—so they voted for Trump, perhaps because they liked his effect on elites.

Figure 3. Real weekly wage/40 for high school dropouts versus college educated.

Usual weekly wages are adjusted for inflation with the CPI.

This figure, which shows a steady rise in the bottom decile of wages since 2015 that continued right through Biden’s term, counters the narrative told by Figure 3. It shows a statistical category that does not correspond to any particular group of workers, whereas Figure 3 shows average income for specific groups. There is a difference between usual weekly wages and hourly wage. The former is what a person earns and includes overtime. The latter is a rate of pay. The starting wages earned by our former foster children and our grandkids1 working in fast food rose from $9-10 in ca. 2018 to $12-14 today. For example, one of them was making $10 at Wendy’s in 2021, left to go to Taco Bell to make $12 (with a $2 pandemic bonus) only to be hired back by the same Wendy’s for $14. All in all, I estimate they saw a ~35% increase since 2018. Over this period one of our grandkids who has worked in fast-food since high school and her husband, who earns about the same, were able to buy a house, tangible evidence of improved economic situation for working class people. My estimated wage increase, after adjusting for inflation, is consistent with the increase shown in Figure 3.

I also note that my grandson, 19 and his sister 20 were looking for and got entry level jobs paying $12 in 2023. He got a job at a pizzeria at $12 and six months later was making $15. He lost the pizza job because he had been rapidly promoted to manager without the necessary maturity for the job. I interpret this to mean that with the ongoing labor shortage store managers were promoting people too quickly in order to justify paying them the higher wage necessary to keep them from going to work for someone else. He recently got a job at McDonalds for $14. I know that this same restaurant had a help wanted sign out last year advertising a $12 wage.

Employers may finally be getting the memo that the world has changed, that $15 is not a manager’s wage, but a regular workers wage. If this is true, this may mean that the $12 offers are disappearing because nobody worth hiring will interview for that anymore. This sort of thing might be responsible for the post-2020 rise in the bottom decile of wages without a corresponding increase in usual weekly wage. The lower end of offers may be disappearing without any material change in what the workers who stay for any length of time earn.

Another way to look at things is through the share of income going to various income percentiles. For example, this figure looks at shares of pre-tax income for the top decile versus the 40-90th percentiles (middle class) since the beginning of 2017. It shows a higher share for the top 10% and a smaller share for the middle class after 2020 compared to before. This figure shows a higher income share for the top 1% today compared to 2019, versus no change for the bottom 50% (working class). This data could be used to support a populist narrative that workers at the bottom did better under Trump, while the rich got richer under Biden.

I suspect it was the economic experience of entry-level workers shown by the HS dropout wage in Figure 3 that helped form working-class political attitudes in the recent election. Over the past forty years, the need to find employment as economic changes made their old jobs obsolete meant blue collar workers sometimes had to begin in a new field at the entry level, which would necessarily pay less than what they had earned as experienced workers in their former field. The potential for being downsized and having to start over from the bottom made working class people more cognizant of labor market realities than college-educated workers, who were often able to find new employment in their field at close to their previous wage when downsized. Entry-level wages for working-class occupations other than trades should tend to build off of a basal unskilled labor price I estimate using the high school dropout monthly earnings. I believe this measure may be more relevant to working-class economic assessments than measures like median income, unemployment rate, or GDP growth.

My wife and I are former foster parents. We remained in contact with some of our former foster kids and their children grew up seeing us as grandparents. We’ve kept tabs on how they were doing over the years.