How SP culture produces financial crisis

Financial crisis leading to a serious economic downturn could provide a resolution to our crisis era

Introduction

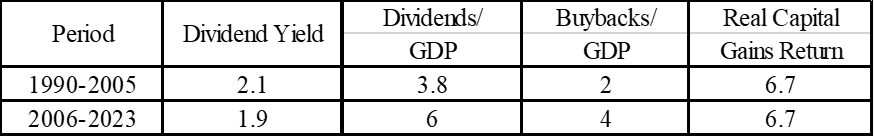

The current secular cycle crisis period discussed in my previous post began with what I call a capitalist crisis, which is characterized by a slowdown in the economic growth trend stemming from a reduction in the productivity of retained corporate profits. This decline in capital productivity could arise if not all retained profits were invested into more productive capital. This has indeed been the case. Three times more economic output (as a fraction of GDP) has been channeled into the stock market through dividends and stock buybacks since 2005 than during the previous quarter century (see Figure 1).

This shift is revealing; average net earnings over 2005-23, less dividends and stock buy backs, were 2.4% of GDP lower than they were between 1980 and 2005. Gross Private Domestic Investment averaged 1.7 percentage points lower, and economic growth 1.4 points lower. It seems that profit previously devoted to investment for growth (an SC culture objective) was now being diverted to financial market appreciation (an SP culture objective).

Figure 1. Stock buybacks since 19801

Retained profits are smoothed with an exponential average (a=0.25). Tax rate is mean of corporate and capital gain rates.

The presumed purpose for stock buybacks is to promote capital gains returns for shareholders in line with SP culture objectives. Executives typically hold large quantities of potential shares in the form of options and personally benefit from rising stock prices, providing an incentive for pursuing them. Reductions in corporate tax rate result in more resources for stock buybacks and dividends, serving to encourage them. Reductions in capital gains tax rates make capital gain and dividend2 income more desirable, which should encourage profit payouts to shareholders rather than retention. These two tax rates were averaged together in Figure 1 to obtain a composite tax rate that shows a steady decline since 1980. As tax rate fell, dividends and buybacks rose and profits retained for reinvestment fell. These tax and investment trends show that SP culture increasingly governed not only business policy implemented by executives, but also the policy preferences favored by economic policymakers. This supports the idea that SP not only defines business culture, but also the beliefs of the economists and politicians who formulate economic policy.

The capitalist crisis as a financial crisis

From an SP viewpoint, capitalism can be seen as a financial process in which firms seek to maximize shareholder financial return. Firms should pay out dividends from their profits to provide the return to which income-oriented shareholders are accustomed, satisfying their objective for owning the stock. Retained profits should then be spent on whatever asset class that will generate the maximum financial return to shareholders. Equity usually outperforms other investment classes, and the insider status of executives makes it even more likely that buying their own stock will give a superior return.

Table 1. Performance of SP executives in delivering gains to shareholders (values in %)

Table 1 shows that executives appear to have followed this sort of approach. It seems that they increased dividend payments as needed to maintain the historical yield, while pouring money into stock buybacks to stimulate impressive capital gains from the onset of the capitalist crisis in 2006 through 2019, despite the second-worst bear market in history occurring over this same period. They had help from the Federal Reserve, who bought trillions of dollars of long-term debt in an effort to reduce long-term rates and stimulate higher asset prices. This intervention shows the influence of SP culture on economic theory and practice at the highest levels.

The capitalist crisis can be recast as a financial crisis by making use of American economist Hyman Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis (FIH). Minsky identifies three distinct income-debt relations for economic units: hedge, speculative, and Ponzi. Hedge financing units are those which can fulfill all of their contractual payment obligations out of their cash flows. Speculative financing units can meet their interest payments from their cash flow but cannot repay the principal and need to issue new debt to meet commitments on maturing debt. Ponzi units cannot even pay interest from their cash flows and must either sell assets or borrow to meet obligations. They typically employ significant leverage in their investment activity. Hedge financing is inherently safe, while Ponzi financing is vulnerable to downward shifts in asset prices. Speculative unit risk is intermediate between these two extremes.

FIH asserts that, over a protracted period of good times, capitalist economies tend to move from a financial structure dominated by hedge finance units to a structure in which there is larger weight to units engaged in riskier speculative and Ponzi finance. Such a rise in financial risk occasionally culminates in a Minsky moment: “when investors are forced to sell even their less-speculative positions to make good on their loans, markets spiral lower and create a severe demand for cash.”3 In a Minsky moment, Ponzi units become vulnerable to bankruptcy. Such bankruptcies can trigger a financial panic. For example, a sharp drop in the stock market resulted in widespread bankruptcies that gave rise to the Panic of 1907. The failure of important firms can trigger panic: Jay Cooke and Co. in 1873, Overender and Gurney in 1884, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad in 1893, and Lehman Brothers in 2008. The 1929 stock market crash was a 1907-like Minsky moment, leading to waves of bank failures in the early 1930’s. All of these financial crises were followed by serious economic downturns.

A shift toward speculative and Ponzi finance should be associated with an increase in the amount of corporate debt and leverage employed for investments, respectively. Corporate debt as a fraction of GDP might serve as a proxy for the prevalence of speculative finance, while stock market margin debt relative to GDP might do the same for Ponzi finance. Figure 2 shows a plot of corporate and margin debt relative to GDP. After four decades at a fairly flat level, corporate debt began a rise to far higher values in the early 1980’s. This trend mirrors a rising trend in the top 1% income share, used here as a proxy for SP business culture. This correspondence suggests the shift from hedge to speculative finance called for in FIH is a product of SP culture, as manifested in the decline in the enterprise premium (see this figure).

Figure 2. Corp. & margin debt as proxies for speculative & Ponzi finance.

Margin data from Vox, FNRA and NYSE. Corporate debt from Federal Reserve.

The validity of margin debt as a proxy for Ponzi finance is supported by the extreme level of margin debt in 1929, when the presence of excessive Ponzi finance was confirmed by the subsequent crash and depression. Margin debt only began to rise above its post-war historical range in the late 1990’s, when over-valuation began to develop and stock buybacks started to become significant (see Figure 1). Ponzi finance is not directly tied to SP culture like speculative finance, but rather to the development of a financial focus by non-financial businessmen, as shown by a preference for stock buybacks over investment after 2000. That is, the rise of Ponzi finance (the chief source of financial instability) appears to be associated with the capitalist crisis. The capitalist crisis is manifested not only as a decline in GDPpc/R (capital productivity) and a slowdown in economic growth, but also as an increased risk of financial crisis. Thus, FIH provides the link between the capitalist crisis and economic collapse that happened during the last secular cycle.

4.2.3 Mathematical modeling of FIH

Economist Steve Keen has developed mathematical models based on Minsky’s FIH that provide a purely economic take on some of the issues discussed above. Keen’s model builds financial considerations directly into a standard model of the economy with three private sector actors: business, whose function is investment, labor, whose function is employment, and bankers, whose function is lending. The basic model has no government actor. A more complex version has government as a fourth actor, whose function is economic regulation. The basic model generates many business cycles of regular length and intensifying amplitude leading to a bubble economy “blow up” and subsequent economic collapse (Keen, 623). Such behavior crudely approximates the economy in the half century before 1933, which saw business cycles of regular length, 27% relative standard deviation (rsd) and sporadic financial crises spaced 4-7 business cycles apart.

Keen models two kinds of government. The first is Minskian government, which acts to stabilize the economy by (a) preventing capitalist expectations from going into euphoria during booms, and (b) boosting cash flows to enable capitalists to repay debts during slumps. Under Minskian government, when falling wages and rising debt cause profit to approach levels that previously induced speculative booms, rising taxation and falling government spending reduce net profit. Conversely, when rising wages and/or debt induce recession, diminished taxation and increased government expenditure boost profits, enabling debts to be serviced. Minskian government intervention greatly diminishes the possibility of complete breakdown, but it does not eliminate cycles. Instead, the system displays cycles of highly variable length (Keen 628). Minskian government roughly describes the period between 1933 and 1981, when SC business culture was dominant. During this period, there were no financial crises and business cycle length showed a large variation (48% rsd), compared to 27% for the preceding era.

Keen also considers government in which rising taxation and falling government spending during boom times is absent, while increased government spending during recession is retained. This government approximates the nature of SP-promoting economic regulation since 1980. With this type of one-sided intervention, the severity of downturns is moderated, while the investment behavior of capitalists is not. Keen writes “increased government spending during slumps would enable recovery in the aftermath to lesser booms; larger booms could result in the rate of growth of accumulated private debt exceeding net profits for some time, thus leading to a prolonged slump” (Keen 631-2). These predictions account for the experience of slow growth in the aftermath of the tech boom of the nineties and the real estate bubble in the next decade. Federal Reserve intervention following the stock market crash between 2000 and 2002 stimulated a real estate boom, which moderated the recession but was followed by a weak recovery. When the real estate bubble burst and the economy turned down, it triggered a financial crisis and the Great Recession from which recovery was retarded.

Keen continues “it also appears probable that a government behaving in this fashion would over time accumulate a deficit, rather than the surplus accumulated in the above Minskian simulations” (Keen 632). During the 1933-80 period, when SC culture was adaptive and the government was approximately Minskian, the trend in Federal debt level was essentially flat, declining slightly from 33% of GDP in 1932 to 32% in 1980, despite incurring massive debt amounting to 60% of GDP as a result of WWII. In the post-Minskian government era after 1980, government debt rose by 24% of GDP to 2000 and, under the influence of the capitalist crisis, another 70% of GDP to 2023. Thus, fiscal balance went from 61% positive from 1932 to 1980 to 94% negative from 1980 to 2019.

I track Minskian financial instability with what I call the Financial Stress Indicator (FSI). Peaks in FSI refer to “financial bubble situations” only some of which go on to produce a Minky moment and financial crisis. Such crises have usually been resolved without a noticeable effect on the progress of the secular cycle and may not even show a political impact. Some crises such as those in 1837, 1857, 1893, 1929, 2008 were followed political regime change, others (1819, 1873, 1907) were not. In two cases, 1857 and 1929, the financial crisis occurred at a time of high PSI, and so was roughly coincident with the start of the secular cycle resolution period in which the problem of elite proliferation was addressed. The 1929 financial crisis triggered the 1929-42 resolution by achieving an across-the-board reduction in elite income/wealth share, solving the excess elite problem. Slavery, rather than financial crisis, was the driver of the 1860-1870 resolution, which was achieved through civil war. Given choices like this, one can understand why I refer a financial collapse rather than the ever more intense political conflict and hatred with which our leaders have saddled us.

Yardeni Research, “Corporate Finance Briefing: S&P 500 Buybacks & Dividends,” 2020

Corporate dividends are taxed as capital gains rates after 2003, before that they were taxed as ordinary income.

Lahart Justin, “In Time of Tumult, Obscure Economist Gains Currency,” The Wall Street Journal, August 18, 2007.