What is Neoliberalism? An empirical and cultural approach.

The Wikipedia entry for Neoliberalism describes it as both a political and economic philosophy. I use the word in its political sense. In this vein, it is primarily employed to delineate the societal transformation resulting from market-based reforms. One objective of this post is to define political neoliberalism (in the context of American politics) in an empirical fashion. I have previously drawn a connection between economic culture (shareholder primacy vs. stakeholder capitalism) and neoliberalism. A second objective is to show how the cultural definition of neoliberalism naturally flows from the empirical one. Finally, I suggest why neoliberalism is bad for innovation and economic growth.

Identifying neoliberalism

For this investigation I start with timing. Figure 1 shows the rise since 1980 in the use of the word “neoliberal” in published books as revealed by Google N-gram. Use of the word neoliberal began to rise in the late 1980’s, implying it referred to changes in how the US economy operated resulting from economic policy pursued by the Reagan administration. Key policy changes were tax cuts and legalization of stock buybacks. Changes in the top income tax rate since 1913 had led to compensation of corporate executives to rise and fall. This had an impact on how executives ran their companies, that is, on the culture of business, that led to different business outcomes, as I have previously argued.

Figure 1. Trends in income inequality, economic culture and frequency of neoliberal in books

Characteristics of neoliberal economic policy

Here I will focus on changes in the trends of corporate profits and their use. Under capitalism, profit is the driver for economic enterprise. Economic growth comes from the investment of profits back into the economy to create more economic output and new kinds of goods and services. If the process of profit generation and reinvestment is adversely affected, economic growth is likely to slow, which I see as a bad thing (I’m an engineer and a political liberal and believe that material and social progress are good things).

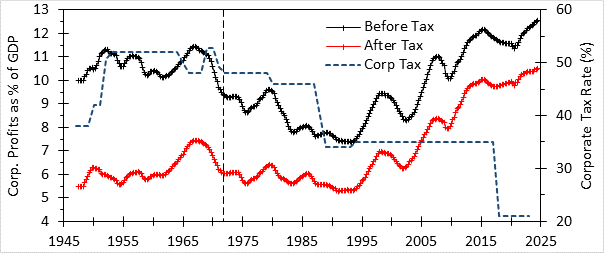

Figure 2 plots before- and after-tax corporate profits since 1947 and the corporate tax rate. Pre-tax corporate profits were strong for more than two decades after WW II. Profits began to fall after the credit crunch in 1966, but the economy soldiered on until late 1968, when it finally fell into recession after the longest expansion up to that time. During the early stages of recovery in 1971, President Nixon ended gold-dollar interconvertibility and corporate profits did not recover to their previous levels during that recovery or the next one. This likely was due to the high levels of inflation in the 1970’s, which distort business planning. In nominal terms, 1970’s profits were strong, it is only when scaled to GDP or expressed in constant dollar terms that the decline is apparent.

Figure 2. Before and after-tax corporate profits and corporate tax rate 1947-present

Values are exponentially smoothed with α= 0.1.

The inability of either Republican or Democratic administrations to bring inflation under control led to the twin Volcker and Reagan revolutions. Fed chief Paul Volcker sought to raise interest rates in order to boost unemployment to levels that would force inflation down. President Reagan took advantage of the Volcker anti-inflation policy to cut taxes and run big deficits, which normally would produce inflation, but not under Fed-prescribed high unemployment. Cuts in corporate taxes from 53 to 46 percent over 1970-79 moderated the impact of declining pre-tax profits on corporate earnings (after-tax profits). The resources executives need for investment into the economy declined only modestly during the 1970’s and 1980’s.

Neoliberalism is not about economic growth; it is about growth of financial wealth

The Tax Foundation states that “corporate income taxes make it more expensive for businesses to invest in technology and equipment that can increase efficiency, produce more product breakthroughs, and generate higher revenue – all things that enable companies to increase wages through raises, bonuses, and promotions, and to create new jobs.” This implies that taxing corporate profits is bad because it leaves less resources for reinvestment. If this is true, then cutting corporate taxes to the point where corporate earnings go up should lead to more investment and growth. This idea turned out to be wrong.

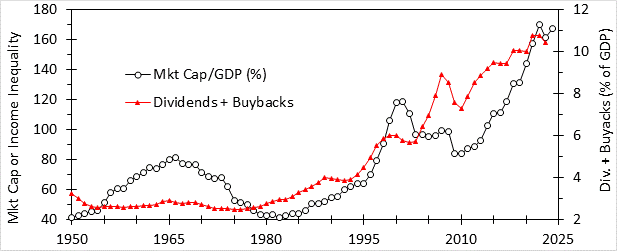

Tax cuts did lead to higher earnings after the 1990 recession (see Figure 2), but did not lead to their increased investment. Figure 3 shows a plot of earnings less dividends and stock buybacks. This quantity would be the resources used to “invest in technology and equipment that can increase efficiency, produce more product breakthroughs, and generate higher revenue,” enabling companies to increase wages and create new jobs, according to the Tax Foundation. Figure 3 shows a relatively constant level of profit reinvestment from the late 1940’s to 1980. With the beginning of the Reagan dispensation (dashed vertical line in Figure 3) a declining trend in reinvested profits began, which has culminated in the modern era in which pretty much all of (much larger after-tax profits) are going to shareholders in the form of dividends or stock buybacks. Also shown in Figure 3 is real GDP growth over time. The fastest growth, averaging 3.8%, was seen before 1981. Slightly slower growth (3.2%) was seen during the 1981-2007 period, and since 2007 growth has been much slower at 2.3%.

Figure 3. Net profit less dividends and stock buybacks and GDP growth over time

Retained earnings exponentially-smoothed with α= 0.2, quarterly GDP growth smoothed with α= 0.03.

One cannot conclude from this data that there is a causal connection between reduced investment of profits and slower growth. It is possible that slower growth (due to other factors) has caused capital allocators to refrain from retaining profit for investment, choosing to return profits to shareholders instead. Whether or not this is correct, it seems clear that recent cuts in corporate tax rates have had no positive impact on either the amount of profits retained for reinvestment or on economic growth. What has happened instead is rising dividends + stock buybacks and stock market capitalization as shown in Figure 4. The Tax Foundation is wrong, corporate income taxes do not adversely impact business capital investment leading to higher wages and new jobs, but rather serve to increase the value of the stock market relative to the economy. As I previously wrote about, injections of money into the stock market by dividends and stock buybacks provide a floor on stock market level from which the market advances.

Figure 4. Trends in shareholder payments and stock market capitalization since 1950

The trends shown in Figures 2 through 4 tell a story of falling corporate tax rates leading to higher after-tax corporate profits. A shrinking fraction of after tax profits has been retained for reinvestment, with a rising fraction returned to shareholders. As a result of these increasing flows to shareholders, the value of the stock market has risen. Over this period the rate of economic growth has fallen. These observations, plus Figure 1 provide an empirical definition for neoliberalism:

Neoliberalism is the political and economic philosophy justifying economic policy changes since 1980 that resulted in higher after-tax profits, a decreasing fraction of which was invested into the economy, with the (rising) balance used to produce higher stock market valuations.

In short, “neoliberalism grows bubbles more than the economy.”

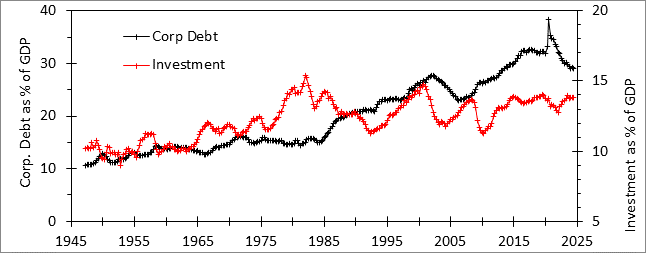

Slower growth reflects change in the kind, not quantity, of investment

The declining fraction of profits used for investment in productive capital and the coincident decline in economic growth rate shown in Figure 3 strongly imply that Business, in its efforts to reward shareholders, is skimping on investments in the real economy leading to declining economic growth rates. But this is not the case. Figure 5 shows that private non-residential investment averaged 10.8% of GDP from the late 1940’ through to the mid-1970’s. After this, it stepped up to an average level of 13.1%. There has been no decline in total investment, despite declining amounts of profits that are reinvested. Debt has increasingly been used to finance investment instead of retained profits. I should stress here that these are collective figures. Plenty of individual companies, tech companies come to mind, have been investing profits back into their businesses. At the same time, other companies have been borrowing money to use for stock buybacks. The two offset each other.

Figure 5. Private non-residential investment and corporate debt level relative to GDP since 1947

So, what is going on? CEOs are incented through stock option compensation to promote increases in share price. With stock buybacks (legal since 1982) they have a second, direct way to increase share price in addition to the indirect route of increasing sales and profits. Figure 4 shows dividends and stock buybacks have steadily risen since 1980 and the stock market with them, showing CEOs have performed in accordance with their incentives. By doing so they have gained great wealth (a key prestige/status symbol) making them role models for other ambitious businesspersons. Economic conditions were conducive to the success of CEOs focused on shareholder value, who transmit their shareholder-focused business style to a new generation of executives. That is, the business environment selected for shareholder primacy culture in an ongoing process of cultural evolution.

A primary ethical value of that culture is a fiduciary responsibility to shareholders to manage their assets for their benefit, that is, to maximize shareholder value. Those in the shareholder primacy cultural “tribe” see corporations using tax cut windfalls to grow share prices rather than the economy as fiduciary virtue, while those not in that tribe see this behavior as a vice, corporate greed. People feel strongly about morality, and these disparate economic cultures are one of the things that divide the country politically.

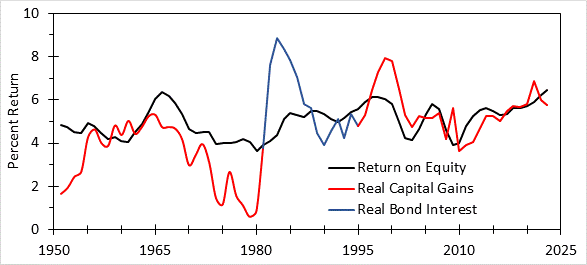

Shareholder primacy doesn’t mean companies stop making productive investments. It does mean the profit potential of productive investment relative to financial returns should be considered. Figure 6 shows a plot of return on equity (ROE), a measure of the real return to shareholders of productive investments, compared to financial returns defined as the greater of capital gains or bond interest. Executives can choose to spend profits on: 1. productive investment (yielding ROE) 2. stock buybacks (yielding capital gains) or 3. dividends that shareholders can use to get bond interest. Since ROE is roughly constant, an executive operating under the shareholder paradigm would choose productive investment when financial returns are poor and pay profits out to shareholders the rest of the time.

Figure 6. Return on equity (ROE) vs. financial returns (greater of capital gains or bond interest)

ROE for 1951-2000 from Poterba and Gomme et al. Post-2000 values estimated from E/R

CEOs could not employ stock buybacks before 1982 and had no way to access capital gains returns. Even if they had that option, they likely would not have pursued it as capital gains returns were often lower than ROE, averaging 3.3% compared to 4.7% for ROE. Bond returns averaged 1.6%, well below ROE, so the only game in town was productive investment. Not only that, but high tax rates constrained executive compensation, so there was no way for investors to incent them to focus on share prices. In this business environment executives invested in order to achieve performance objectives other than share price in order to beat the competition and “win the game” and so achieve the prestige and status that make them role models. Economic conditions simply were not conducive to the success of CEOs focused on shareholder value. The pre-neoliberal environment selected against shareholder primacy culture.

From the observations in this section, I can give an alternate, cultural definition for neoliberalism:

Neoliberalism is the political and economic philosophy justifying policy changes that select for shareholder primacy business culture

This is the definition I use, but it requires a lot of background information for it to make sense.

Why neoliberalism, and shareholder primacy is bad for economic innovation

In the environment created under neoliberalism, innovative startups and young public companies enjoy an advantage over larger established companies pursuing innovation. Having negative earnings, their valuation in the eyes of investors is based solely on their perceptions of their future promise, on “vibes” rather than a rational calculation of future reality. The reality of “vibes valuation” is demonstrated by Bitcoin and other crypto assets. The first bitcoin issued was priced by its creator at $1. Today such coins are valued at nearly $70,000. The characteristics of the coin have not changed. It provides no income or other benefit of ownership. Its value is solely as an object of speculation like tulips in 17th century Amsterdam or Beanie Babies in the 1990’s. Yet its high valuation has persisted much longer1 than previous speculative objects.

In a world in which an objectively worthless entity can sell for $70,000, what will shares in a business creating the future be worth? The amount of investment that can be elicited on vibes alone2 is limited. This favors innovations that require relatively little capital investment, such as software. Also favored are innovations creating more efficient ways to extract profit from existing markets, which are easier to pitch to venture capitalists. Such innovations reflect shareholder (investor) primacy cultural values.

This environment disfavors innovation by established companies. There is no free vibes money—investing in new things means diverting cash flows away from shareholders. Invest too much and your stock tanks, affecting your compensation. This acts as a negative feedback on economic development by established companies, which are, after all, the bulk of the economy. Before 1981 new technologies were often developed by large corporate research labs such as those at Bell, DuPont and Xerox. This is less common today.

Noah Smith wrote an interesting piece about the role played by large company innovation in the world before neoliberalism. He writes:

Research discoveries and fundamental inventions are public goods, because they have a strong tendency to leak out across organizational boundaries, making it impossible for whoever did the research to capture the monetary value. The transistor was invented (discovered?) at Bell Labs, by John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley; how much of the total monetary value created by transistors was captured by those individuals, their research teams, or Bell itself? Very, very little of it. This means that private companies have very little monetary incentive to do basic research.

Smith’s economics is correct. My thesis is that economics is a subset of culture and so follows the same mechanisms of cultural evolution as does everything else. Businesspersons operate under business culture and respond to business status symbols such as capturing monetary value. Scientists operate under scientific culture where status is based on the utility of the new knowledge they create as judged by their peers. The Bell Labs scientists did not need to capture the monetary value of their invention; they won the Nobel Prize!

As I previously described, the industrial research lab was the result of capitalists applying capital to the process of innovation. After WW II, Smith writes, “the government started supporting universities a lot, both with money, and with legal changes (especially the Bayh-Dole Act) that allowed universities to profit from licensing their research to private companies.” This created “a sort of supply chain for innovation—universities do the scientific research, startups and university spinoffs and mission-oriented government agencies like DARPA turn insights into inventions, and big companies acquire the inventions and focus on turning them into products.”

But he cites work noting a couple drawbacks of this university-based system:

[There are] several attractive features of big corporate labs that the new innovation supply chain might lack. First of all, while many university researchers focus on questions of general scientific interest (how the Universe was formed, for instance), corporate labs tended to focus on the creation of general-purpose technologies—things that had lots of pragmatic industrial uses, like transistors…Second, corporate labs tend to be multi-disciplinary, pulling in researchers from a wide variety of fields and having them work together on projects, while university research...tends to be very siloed by discipline.

This is an important point. The complexities of modern science and engineering require multidisciplinary teams. In academia, science is typically carried out by research teams (grad students and post docs) overseen by a principal investigator, who must wear many hats: teacher, salesman, manager, grant writer, politician, writer, in addition to scientist. A lead scientist in industry roughly corresponds to principal investigator who are relieved of the need to be salesman, manager, grant writer, or politician, making them more productive.

This is because there is twice as much money, relative to GDP, in hands of the investing class as in the past, meaning much more appetite for speculations like Bitcoin.

Bitcoin has a track record of more than a decade of rising prices based on vibes. Without a track record. vibes have less power.

I'd prefer going to Bill Michell and Philip Mirowski. Neoliberalism intellectually started with Mont Pelerin and the Think Tank-–university complexes they developed. You can trace all the crud back to them. It was ostensibly an attempt to never have Nazi's rise ever again. A decent motive. But motives are only ethical when based on truth. They understood macroeconomics completely backwards, since proto-neolioberalism (aka. austerity politics) under German's Ch. Brüning was the fuel for the Nazis.

Well-said. Neoliberalism is capitalism on steroids. And just like actual steroids, it creates a collective action problem and enshittification for all, and it ultimately backfires on the "juicers" as well.