An Introduction to Leading Sectors

The raw material of economic growth

To produce maximal economic benefits for working Americans it is necessary to achieve low unemployment levels and low inflation rates under a business culture that prioritizes real growth over rising financial markets. As previously described, this is best achieved under stakeholder capitalist rather than shareholder primacy economic culture. Optimal policy is necessary, but not sufficient for strong growth. One needs grist to grind and so strong growth requires lots of opportunity for growth as well as good policy. Opportunity consists of new demand which entrepreneurs can tap. Meeting this new demand produces a new fast-growing portion of the economy called a leading sector. This post is concerned with this phenomenon.

The Harvard economist Joseph Schumpeter attempted to build a theory for the capitalist process. His view was that business cycles reflected the impact of concentrated bursts of innovation which transformed the economy. He coined the term “creative destruction” to describe how the creation of new industries and superior business methods in existing industries partially or wholly replaced (destroyed) old industries and methods. These new industries and methods can be described as a “new economy”, both adding to and partially replacing the old one. The development of a new economy creates new areas of economic activity that did not exist previously. These new areas (leading sectors) then grow strongly for decades as they spread into every part of the economy. Leading sectors compete with existing business for labor, boosting wages, which in turn which incents existing businesses to invest for high labor productivity.

Since Schumpeter’s time, his ideas have been extended and formulated in different ways by a number of researchers. Gerhard Mensch developed a more explicit model for Schumpeterian innovation that related it more closely to Kondratieffs. The business consultant and popular financial writer Harry Dent describes an innovation wave that is similar to Mensch’s concepts, but with some new twists. Here I give my own take on the innovation wave. I will use Dent’s terminology and conceptual scheme, as it is easy to understand, but will come up with a somewhat different detailed formulation.

New products and technologies typically go through three stages of growth: an innovation phase, a growth phase and a maturity phase. These three stages are shown graphically by what is called the S-curve (see Figure 1). Dent defines the period during which penetration increases from zero to 10% as the innovation phase of the S-curve. The period from 10% to 90% penetration is called the growth phase. Finally, the period from 90% and up is termed the mature phase.

Figure 1. The S-curve

Dent extends the S-curve concept to the entire economy. He notes that some periods are richer in entrepreneurial activity than others. One such period was around 1900, when many mass-market brand-name products like Gillette razors, Coca-Cola or Ford automobiles were introduced. Following Mensch, Dent calls the innovations associated with these entrepreneurial periods “basic innovations”, because they form the base for a new economy. He calls periods in which the basic innovations appear the innovation phase for the new economy. The period around 1900 is then the innovation phase for the “mass-market” economy. Initially, the basic innovations operate on the margins of the old economy. As the basic innovations move into the mainstream, these new industries enter their growth phase. Thus far, the development of the new economy follows the same S-curve as the development of an individual product or technology, with an innovation period (0-10% adoption) followed by a growth phase (10-90% adoption) as depicted in Figure 1

Figure 2. Diagram of Dent’s Innovation Cycle

The next phase of the developing economy is the shakeout. The shakeout occurs when many firms, attracted by the opportunities of the growth phase, enter the business and encounter increased competition as the market becomes saturated. Saturation results in increased price competition and business failures. The shakeout is a period of deflation and depression. It is also a period of innovation, but of a different sort. New technologies and products are developed that complement and improve upon the basic innovations. Dent calls these “maturity innovations.” Of the many new-economy companies that existed at the end of the growth period, only a few successfully employ the complementary maturity innovations and products to win the competition and survive the shakeout. Following the shakeout, a new growth period begins, during which improved versions of otherwise mature products are sold. This period is called the maturity boom.

Another way of describing the maturity boom is the growth phase of the mature-type innovations. In this concept the shakeout is the overlap of the basic innovation's mature phase and the mature innovation’s innovation phase. The S-curves for the basic and maturity innovations are combined into a composite “double-S” curve that I call “the innovation wave.” To illustrate this concept, I focus on what Dent calls the mass-market economy, which is the most recently completed innovation wave (full treatment can be found in my book Stock Cycles). I identified industries that became or were important during the first three quarters of the 20th Century. The scheme shown in Figure 2 can then be applied by compiling S-curve data for these industries.

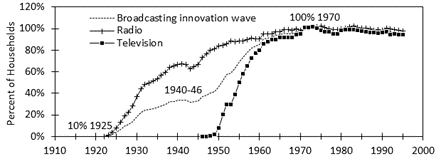

Figure 3. Market penetration curves for broadcasting showing the innovation wave

Broadcasting provides a good example of an innovation wave. Broadcasting started with the development of voice radio transmissions in the 1906-1917 period. The first radio station went on the air in 1917 and the dominant radio company of the era, Radio Corporation of America (RCA), was spun off from General Electric in 1919. RCA and others developed television during the 1926-1939 period. The first US television station went on the air in 1939 and the first major television network (NBC) was established by RCA in 1941. A second wave of growth in broadcasting got underway after this. Figure 3 documents this entire process by showing the growth in the percentage of households with radio and television sets over the 1922-1995 period. We see growth curves for radio and television that strongly resemble Figure 2. In Dent’s terminology, radio would be the basic innovation and television would be the maturity innovation. If we average the two curves together, we get the broadcasting innovation wave, which shows an initial growth period up to around 1940, a flat period to 1946 and then resumption of the trend upwards to a peak in 1970. By analogy to Figure 2, we denote the radio growth phase as the growth boom (1925-1940) and the television growth phase as the maturity boom (1946-1970). The flat period in the composite curve (1940-46) becomes the shakeout. I identified 1925 as the beginning of the growth boom, since that is when the composite growth curve reached 10% of its 1940 level.

Figure 4. Market penetration and productive curves for automobiles

We now turn to the auto industry. Figure 4 shows two kinds of curves. The first is a plot of the total automobile fleet divided by the labor force, which shows the growth of the auto in terms of market penetration. This curve is shaped much like the prototypical innovation wave in Figure 2. There is a definite growth boom up to 1929, a shakeout from 1929 to 1949 and a maturity boom from 1949 to 1973. Unlike with radio and TV, where the basic and maturity innovations reflect distinct products, auto’s maturity innovations included such things as the automatic transmission, power features and the interstate system, which made using a car for personal transportation more appealing to a broader spectrum of the public.

The second curve in Figure 4 shows the annual production of vehicles per million (constant) dollars of GDP. This ratio indicates the importance of the auto industry relative to the economy as a whole. As a major economic element, the auto industry peaked in the 1920’s, though it retained its dominance until the 1950’s. The initial growth in the auto industry reflects the growth boom in market penetration. We can date the beginning of this growth boom as the point when production of cars reached 10% of the importance it would have at the growth boom peak in 1929. Thus, we would date the growth boom for the auto as 1907 to 1929, the shakeout from 1929 to 1949, and the maturity boom from 1949 to 1973.

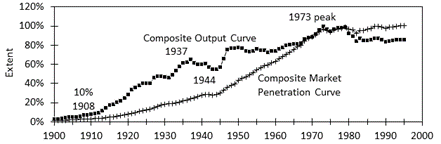

These examples illustrate the use of market-penetration and production-volume curves. Market penetration curves are those that measure the extent to which the innovation has saturated a market (the broadcasting innovation wave is of this type). Volume curves use the levels of physical output relative to GDP (in constant dollars) as a measure of the extent to which the new economic activity has diffused throughout the economy. It measures the economic penetration of a new innovation (or cluster of innovations). To apply this graphical analysis to a whole new economy, we obtain as many curves of either sort as we can for important industries in that economy, and average them together to produce composite market and economic penetration curves. These curves are then inspected to obtain the dates of the growth boom, shakeout, and maturity boom.

Table 1. Mass-market economy industries

Innovation waves were constructed for nine industries and estimates for growth and maturity booms obtained (see Table 1). Production volume data was averaged together to form a composite output curve. Similarly, market penetration data was averaged into a composite innovation wave. The composite profiles appear in Figure 5, and these curves show the growth of the mass-market economy in terms of both output (economic penetration) and market penetration. The output curve shows a broad top from 1973 to 1979, after which it starts to decline. The market penetration curve shows a plateau after 1973, indicating that the mass production economy industries as a whole saturated their markets after 1973. With these observations, we would put the “economic peak” or end of the maturity boom of the mass-market economy in 1973. The output curve shows a dip from 1937 to 1944 that can be interpreted as the shakeout, making between 1944 and 1973 the maturity boom. For the start of the growth boom we use 1908, when economic penetration reached 10% of the 1937 level.

Figure 5. Composite innovation wave for the mass-market economy

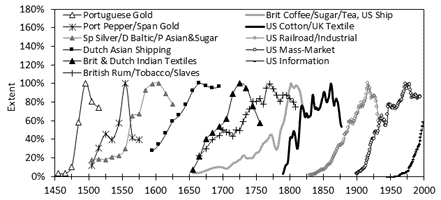

Modelski and Thompson’s leadership cycle proposes that future hegemonic powers develop leading sectors of the world economy prior to becoming hegemons. These leading sectors appear to be innovation waves pioneered by a nation who is able to become hegemonic because of them. Each is established by fundamental innovation(s), which could be discovery of new lands or new markets, discovery/development of new crops or products for trade, or the opening up of existing markets that had previously been closed. These innovations give birth to a new leading sector, exploitation of which provides the material resources that underly the military power required to become hegemon. Modelski and Thompson assert there have been four leading powers since 1500: Portugal, the Netherlands, Great Britain and the United States. Figure 6 shows innovation waves for these successive leading sectors. These waves are spaced 53±8 years apart and are correlated with Kondratieff cycles. Note that the countries associated with the leading sectors often signaled a future hegemon. American leading sectors form the last four “waves” in Figure 6, showing the economic prominence of the US in cycles 8-11. Similar is the British involvement in waves 5-8, the Dutch involvement in waves 3-5, and the Portuguese in the first three waves.

Figure 6. Successive innovation waves in the world economy

Note that the first four of these innovation waves played out before the appearance of capitalism around 1670 in Britain (see Figure 1 here). These leading sectors provide lessons for today. The driving force behind their development was the state. England played no significant role in any of these leading sectors; it was crafting a domestic economic policy (capitalism) intended to achieve similar benefits to the state as these sectors as described in my previous post. Note that Britain played a staring role in the next leading three sectors after the appearance of capitalism, which led to two successive Leadership cycles of British hegemony. Capitalism was originally a creation of the state, invented for state purposes. It was not a natural outcome of a market economy. Thus, it is a long-established and legitimate role of government to intervene in or even engage on economic activities (i.e., industrial policy), when necessary, to achieve compelling state purposes. Avoiding the nastier outcomes of a secular cycle crisis resolution constitutes such a compelling purpose, providing justification for deliberate state action to encourage development new leading sectors such as green energy, as well as promote SC culture.