Why America doesn't build things

The effect of economic policy and the business culture it creates

Economics writer Noah Smith’s recent piece The Build Nothing Country discusses the difficulties encountered in constructing urgently needed infrastructure, housing, or pretty much anything else in modern-day America. He identifies the immediate cause of this stagnation as NIMBY opposition to development. Smith further characterizes this NIMBYism as a special kind of subsidy the government provides its citizenry:

If you’re one of the roughly 2/3 of Americans who owns a home, you can raise your wealth — at least on paper — by going to local government meetings and arguing to restrict the local housing supply. But perhaps just as importantly, you can preserve the built environment around you in exactly the form you’re used to. You can keep your streets quiet and uncrowded. You can preserve your open space, your big lawn, and your scenic views. You can keep your neighborhood free of any poor people who might live in nearby apartments or ride a train to your area. You have the option to keep your area free of anything you don’t want, for any reason.

It’s not literally true that the government offers an option to block development as a benefit to voters for voting for the status quo year after year. Smith is speaking figuratively. What he means, as he describes earlier, is that a determined party can use existing environmental law or regulations to block, or at least slow down, any development project they oppose. This practice could be curtailed or at least discouraged via legislative action. That this has not happened is what constitutes the government subsidy. Smith concludes “we no longer have the luxury of giving our people a shadow subsidy by freezing their neighborhoods and cities in amber….Slashing the thicket of red tape that prevent development and subordinating local interests to the needs of the nation…are immediate necessities.”

Smith does not explore how this subsidy came to pass. It is natural for people to desire for things not to change. What has changed since the 1970’s is it became possible for people to impede development without the authorities intervening on behalf of the project sponsor. At some point, it appears, the political clout of project sponsors became less than that of the opposition. I see this shift occurring as a result of the changes in government economic policy in the 1970’s and 1980’s, particularly reductions in the top tax rate, the shift to chronic deficit spending, and the complete outsourcing of inflation control to Fed-directed interest rate policy.

The way this happened was cultural. SC and SP capitalism in Figure 1 refer to the prevalent business/economic culture under which market capitalism operates. SC capitalism focuses on the accumulation of “real” capital, stuff that when combined with labor increases its productivity, leading to increased sales and profits, allowing more real capital to be created. SP capitalism focuses in the accumulation of the financial representation of capital represented by market capitalization, an objective often called “shareholder value.” Culture, like genes, evolves over time in order to become better adapted to the environment. Figure 1 shows the output from a cultural evolution model in which business culture evolves to adapt to a changing environment (E).

Figure 1. Evolutionary shifts from SP to SC capitalism and back over the past century

As suggested in the figure, I employ economic inequality (top 1% income share) as a proxy for the relative amount of SP present in business culture. E is a function of top tax rate, interest rate and strike frequency. E shifted from a high value during the 1920’s (for which SP is adaptive) to a low value over ca. 1940 to 1985 (for which SC is adaptive) and back to a high value after 1985. The evolutionary response by business culture followed the shifts in E with a significant lag. For the full development of this idea see chapter 3 of America in Crisis.

As capitalism became more SP-flavored over the 1990’s, fewer capitalists would be inclined to focus their lobbying efforts on clearing away NIMBY obstacles to accumulation of real capital. Why build real projects that might create increased profits causing investors to value your stock higher, when you can grow shareholder value directly through stock buybacks? As I showed in Figure 1 in a previous post, addition of a growing flow of money from stock buybacks into the market since the late 1990’s has served to put a higher “floor” on the stock market, resulting in a higher market capitalization than would otherwise exist. During the 1980’s when SC capitalism was till prevalent and investment in real things still something valued, such investment was discouraged by the negative enterprise premium present at the time (1981-90 enterprise average premium was –0.8%, see Figure 4 in my capitalist crisis post). A negative enterprise premium means the return available from business is less that that available from less risky financial investments like stock buybacks, dissuading SC businesspersons from investing in real capital, that is, building stuff.

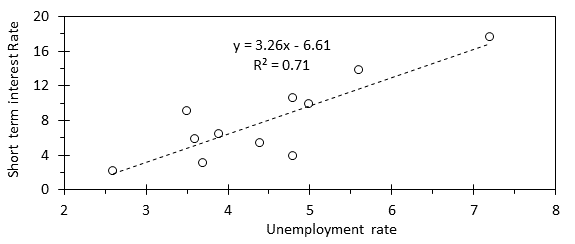

A simple exercise shows how government policy created this outcome. I collected the interest rate associated with upticks in unemployment resulting from Fed tightening at the ends of economic expansions since 1950 and plotted them against the unemployment rate at that time. Figure 2 shows the relation between how high the interest rate must be raised to initiate unemployment increases to fight inflation and the prevailing unemployment level. The lower the unemployment rate, the lower the interest rate needed to initiate inflation control. The unemployment rates in Figure 2 are generally below the estimated NAIRU at the time (average 1.1 points lower), which is why inflation was a problem. This means lower interest rates will be associated with lower NAIRU.

Figure 2. Interest rates at peak employment as a function of unemployment rate

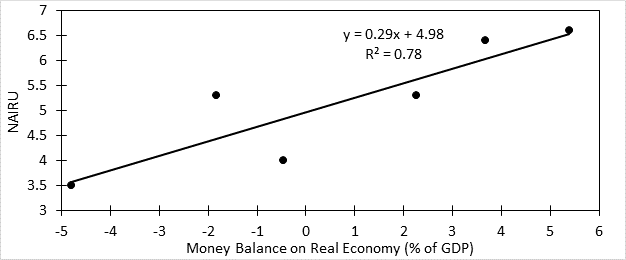

Figure 3 shows NAIRU as a function of the money balance on the economy with a slope of 0.29. This means that, all else being the same, a 1% rise in deficit spending translates to a 0.29 point rise in NAIRU, and the minimum unemployment rate reached when interest rate hikes must be used to control inflation. With this result, and the relation given in Figure 2, I conclude that a 1 point increase in deficit spending translates to a 0.95 point increase in interest rate (and corresponding reduction in enterprise premium). By choosing to cut tax rates, rather than raise them to finance the ongoing military buildup, the Reagan-Bush government chose to run deficits over 1981-90 that were two percentage points higher than during the 1970’s, which meant a shift from a mildly positive enterprise premium of 1.1% to a negative value of –0.8%. Had the Reagan administration been as fiscally responsible as the Eisenhower administration, the enterprise premium would have been a strongly positive 2.6% and things would have continued to be built until the culture turned against it in the late 1990’s.

In the mid 1990’s, the enterprise premium shifted positive due to an improving fiscal balance (coincidently, an uptick in productivity happened around the same time). Had the cut in the capital gains tax in 1997 not happened and George Bush not been nominated as the Republican candidate in 2000, the positive enterprise premium would have been sustained and E in Figure 1 would have remained at 1990’s levels. A return to a world in which America built stuff might have been possible then.

Figure 3. NAIRU versus money balance on the real economy from inflation post.

Between 1945 and 1980, the combination of SC culture and positive enterprise premium ensured there would be strong capitalist desire to build stuff. But what about the period before the Depression, when culture was SP, yet stuff was still being built? How does this fit in? As I noted in the stock market paradigms post, before 1916, stock prices were quoted relative to a par value, like bonds. The concept of shareholder value as indicated by share price, as opposed to the income stocks generated, did not really sink in until the 1910’s. Prior to this SP capitalists sought to achieve shareholder value by building profitable companies that paid big dividends, not by trying to juice stock prices. Even speculator CEOs like Jay Gould, who would use selected buying and selling to manipulate stock prices, did so to acquire valuable real assets at bargain prices. Though culturally an SP capitalist, Gould’s actual business behavior was similar to that of an SC capitalist. Because stocks were seen as like bonds, speculation was necessarily a zero-sum game and so the idea of spending profits to sustainably bid up prices simply wasn’t something that was done. This may have changed in the 1920’s bull market when soaring prices suggested that companies buying their stock could indeed produce higher shareholder value solely due to the price increase. But then the market crashed and stock manipulation by companies (e.g. stock buybacks) was made illegal in 1934, which precluded further development along these lines. Stock buybacks were made legal again in 1982 and as SP culture returned in the late 1990’s, so did stock manipulation by companies in the pursuit of shareholder value.

Noah Smith says we must return to building things or “someone else will build the future on the bones of our civilization.” I agree, but to do that we need to restore SC culture. Otherwise, as I wrote in chapter 7 of America in Crisis “continuing to maintain SP culture, as the US government has been doing, amounts to choosing cultural suicide for Western Civilization.”

Michael Pettis who abodes in china has written alot about the financial basis of the loss of manufacturing . It about the dollar system that aids the political and foreign policy elites but hamstings the manufacturing elites