Why Progress Seems Stalled

Faith in Progress has declined as recent advancements have disappointed

There are a number of Substacks devoted to progress: Roots of Progress, Risk and Progress, From Poverty to Progress. Most of these seem to be a response to public pessimism about the future. For example, Jason Crawford writes about how people no longer seem to believe in progress:

In 2023, over three quarters of Americans did not believe that life for their children would be better than their own, and only 24% were optimistic about the country’s future. Most worrying is that young people are particularly pessimistic: in a recent youth survey on climate change, 75% thought that “the future is frightening” and more than half agreed that “humanity is doomed.”… if society believes that scientific, technological and industrial progress is harmful or dangerous, people will work to slow it down or stop it. Activists have obstructed all forms of energy—nuclear power, oil and gas, even solar and wind—and the average American benefits from no more energy today than fifty years ago. The EU has largely banned the cultivation of GMOs, and opposition to Vitamin A–enhanced “Golden Rice” has prevented it from “saving millions of lives and preventing tens of millions of cases of blindness.” Sri Lanka created a food crisis for itself when it banned synthetic fertilizer in a hasty, bungled shift to “organic” farming. In medicine, romantic notions of “natural” health cause patients to shun treatment for cancer and vaccines for diseases; measles outbreaks are now on the rise.

Crawford points to exciting new developments:

On the horizon, powerful new technologies are emerging, intensifying the debate over technology and progress. Robotaxis are doing business on city streets; mRNA can create vaccines and maybe soon cure cancers; there’s a renaissance in both supersonic flight and nuclear energy. SpaceX is landing reusable rockets, promising to enable the space economy, and testing an enormous Starship, promising to colonize Mars. A new generation of founders have ambitions in atoms, not just bits: manufacturing facilities in space, net-zero hydrocarbons synthesized with solar or nuclear power, robots that carve sculptures in marble.

With the exception of robotaxis and mRNA vaccines the things he mentions are speculations. Supersonic flight and nuclear energy are 1960’s technologies. The launch rate SpaceX has achieved with their reusable rockets is truly impressive, but rocketry is not really the product they offer. Most of the payloads they are putting into orbit are SpaceX payloads in support of their Starlink internet service. SpaceX is basically a telecommunications company with rockets. Its rockets certainly make space more accessible, but since there is no “space economy” this enables, what’s next after they complete Starlink?1

As for robotaxis, think of them as Uber with robot drivers. The user experience is basically the same. The rise of ride-hail services like Uber and Lyft has led to a reduction in use of public transit and increased congestion in cities with high prior public transportation use. Presumably, robotaxis will be cheaper than Uber and likely to exacerbate these trends. Those using robotaxis will enjoy lower prices, while less transit use will lead to quality declines for those still relying on it and increased congestion will negatively affect those still driving their own cars. The overall effect on the public will be mixed. The clear winners will be the owners of the robotaxi companies who will become rich. Recent discussions about the enshittification of internet, have concluded that that it is the owners of the tech companies who have received most of the value their innovations created. This is the problem with so much of recent innovation. Much of it seems as a way to provide the same stuff we had before, but at a somewhat lower price while extracting a larger amount of the sales as profit.

It used to be different

Now compare this to the sorts of innovation we had in the mid-twentieth century like household appliances. A task like laundry that at the beginning of the 20th century was a back-breaking work that took all day, and which was performed by servants (7% of the workforce in the late 19th century were employed as servants). During the 1960’s, lower middle-class households like the one I grew up in, were obtaining automatic washers and dryers that converted a once arduous task into a light chore even a child could do that required only minutes of work. Refrigerators, dishwashers, and microwave ovens were among a vast array of kitchen appliances that transformed food storage, preparation and cleanup into much less time-consuming tasks. Automobiles allowed people to live farther from their place of employment, opening up more space for bigger homes with yards. Bigger domiciles meant more demand for appliances and furnishings—and more jobs for those who made and serviced such things—resulting in strong economic growth.

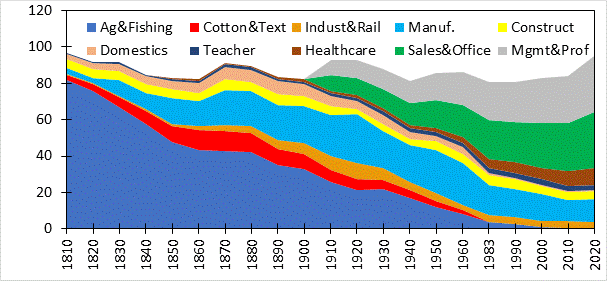

A key difference between innovation today and that of the past is the latter involved the creation of new categories of demand. New categories of demand are new products or services that do not replace anything, creating new economic sectors than add onto pre-existing ones, enriching the nation. Creation of new economic sectors means new occupations. Figure 1 provides an overview of how the US economy changed over time in terms of occupations. It shows estimates for the fraction of workers employed in various job categories.

Figure 1. Evolution of occupational categories over time

In 1810 the vast majority of Americans were engaged in agriculture, while very few are today. Yet the absolute size of the agricultural sector is, if anything, larger than it was then on a per capita basis. Farmers are so much more productive today. Today fewer than 1% of the workforce is needed to do what 80% did 1810. As agricultural productivity rose, those no longer needed on the farm took jobs that were being created by new leading sectors such the cotton/textile economy shown in red in Figure 1. This is the eighth leading sector in this figure. The ninth sector, the railroad/industrial economy, is depicted in orange in Figure 1, while the tenth leading sector roughly corresponds to the light blue area in Figure 1. These three leading sectors peaked around 1860, 1920 and 1970. The widths of the corresponding swathes in Figure 1 begin to shrink after these dates, as agriculture did before them.

Also shown in Figure 1 is information about some typical occupations for which I could find data: construction, domestic servants and teachers. Productivity for these workers has been about the same so the relative numbers of these workers reflects demand for their services. For example, the number of domestic servants has dropped precipitously with the advent of household appliances that perform the functions these workers once did. Construction workers and teachers have maintained a roughly constant share of the workforce due to the continuing need for their services. The last three occupations have shown rising fractions with time and reflect the transition from a goods-producing to a services-based economy. I do not have a category in Figure 1 that corresponds to the 11th leading sector, the current information economy. This economy is centered around the personal computer and telecommunications technologies as the core innovations. As befits its name, much of the employment created by the information economy falls into the business and professional occupations represented by the green and gray regions in Figure 1.

The early portion of the leading sector (which I documented in my 2000 book) created new categories of demand for home and personal entertainment: cable TV, VCR/DVD, videogames; for personal information technology: PCs/lap-tops, video cameras, GPS; and for personal communication: cellphones. All of these things created new budget items in American households and revenue streams supporting new businesses and jobs that added on to existing businesses and jobs, enlarging the economy. Based on the fifty-year Kondratieff timing of successive leading sectors and the 1973 peak of the mass market leading sector, the information economy should be peaking now with the innovation phase of leading sector #12 already underway (robotaxis and GPTs are examples).

The problem today

The malaise that Crawford identifies is largely a manifestation of how the information economy has played out since 2000 (and how the next one may unfold as suggested by the robotaxi discussion). The worry is that much of the later development of the information economy, such things as e-commerce, social media, Uber, AirBnB, Door Dash, internet search, and streaming services have either not created new categories of demand or have no value proposition. Ride-hail, e-commerce, e-delivery and e-motel aps are simply more efficient ways to do existing economic functions. Their chief function is to achieve more efficient profit extraction from a given volume of economic activity. Social media and internet search have problems with their value proposition. These services were initially offered at no cost. Doing this establishes that what they have to offer is not worth paying for. So how do you monetize this? The answer is the same way the media products of railroad-industrial economy (newspapers & magazines) and the mass production economy (broadcast radio and TV) were monetized: advertising. But advertising is an expense for sellers of non-media goods and services, and has averaged about 2% of GDP over the last century. As multiple social media, search engines, broadcast and print media all compete for this same stream of advertising dollars there will be winners and losers in a zero-sum gain. They can be no growth, no progress here. It is a dead end, a dog chasing its own tail. It is this quest for revenue that has led to the enshittification of the internet. Finally, there are streaming services and new social media like Substack, in which people pay for media entertainment or information as they have previously done for movies, books and magazines. These have the potential for being new categories of demand if they manage to bring something new to the table. There is one exception, the smartphone, the only clear-cut creator of new demand in the latter half of the information economy that came to my mind.

The question is, why have things evolved in this way since the advent of the 21st century? The answer, I believe, is shareholder primacy (SP) business culture, which has become dominant since 2000. The most important task of a capitalist chief executive is capital allocation. An executive operating under SP culture seeks to maximize shareholder value (stock price). Thus, when considering whether to invest in a game changing idea (i.e. one that might lead to a new category of demand in which his firm will have first mover advantage2) they must weigh the probability of success,3 and its effect on stock price, against the prospect for higher stock price achieved through stock buybacks. Table 1 shows that over the last six years, the CEOs of the companies making up the S&P 500 have collectively made the decision that the latter is the better course of action. After dividends and stock buybacks only 0.8% of corporate earnings were retained for potential investment.

Table 1. Earnings, Dividends, Stock Buybacks and Retained Earned for the S&P 500.

One can argue that the sort of established firms making up the S&P 500 are too stodgy to invest in groundbreaking technology. But this was not true in the past. Significant new technologies were developed in corporate laboratories. Arora and co-workers document a shift away from scientific research by large corporations as SP was replacing SC culture in executive suites in the 1990’s. Crawford’s piece points to startups as a source for innovation. But startups function more as financial investments than leading sector innovators. Some bit of tech around which a good story can be constructed is built to attract venture capitalist (VC) money, with the idea that after a period of financing a successful startup will be able to go public with a big payday for the VC’s. Such a story will seem a safer investment if the innovation yields more efficient profit extraction from an already-existing market.

So how was it different in the past?

The simple fact is investment in real stuff that generated rising productivity and created jobs in the past did not earn the kind of returns that one can get with financial investments today. Thus, pouring all their profits into the stock market rather than investing in productivity-enhancing technology, as Noah Smith would like companies to do, just makes sense given the objective of maximizing shareholder value. The reason why we had the storied Bell Labs and other large-scale corporate research outfits flourish in the postwar era was because government economic policy deliberately suppressed financial returns. The effects of this policy are shown by my enterprise premium measure, which is the difference between real after-tax return on equity from business (i.e. return on “real” capital) and financial returns. Enterprise premium was higher before 1980 than after as I show in this figure,

And there was more, stock buybacks were banned back then, while dividends were taxed at rates much higher than today, discouraging paying out all profits as dividends. Executives disbursed about half of company earnings as dividends over 1946-80, leaving the rest available for investment in growth. Though return on equity was lower than today, it was still higher than financial returns, and so that is what they did. Also, the higher top tax rates on ordinary income meant it did not make sense for boards to pay high levels of stock option compensation to executives, and so their income during the 1945-80 period was considerably lower than before 1940 or after 1980, and their income was not tied to stock price.

Business culture back then did not focus on shareholder value as the primary concern because (1) they were not incented to do so, (2) there was no easy mechanism to do this, (3) it often did not make financial sense. So, they didn’t. Curiously, despite being paid much less back then than today, people were still eager to do the job of CEO, or college football coach, for that matter. The reason why is that executives are cultural primates like the rest of us and are motivated to acquire prestige--to become one of the cool kids. One does this by acquiring symbolic markers of success. Money (market capitalization) is one of these, which plays a major role in SP culture, but there are other ways to gain prestige, like winning the competition. CEOs would be rated on how they did on business fundamentals such as gains in market share, new product development, or sales and profit growth, much as are athletes on the fundamentals of their sport. Another source of pride would be their organization’s prestige in the eyes of the public.

So how to bring back progress?

Restore SC culture for starters. More on this in a later post.

I have some ideas, which I plan to write about.

Examples of success: Apple II, Mac, iPhone.

Examples of failure: Apple III, Lisa

Nice piece Mike . It feels that progress has stalled, or slowed, after 1970. Some have blamed this on a lack of energy abundance, owing to both the oil crisis and degrowth movement that took hold at the time. Something I discussed at Risk & Progress.

I am not entirely sold on this idea. It's true, progress shifted from atoms to bits and the growth in the consumption of energy ( and GDP growth rates for that matter) all slowed around the same time.

I could make the case, however, that this is because of the nature of the information revolution. We just don't need as much energy to run a computer than we did a washing machine. Further, because the fruits of the IT revolution are mostly intangible, they are much harder to quantify and account for when we calculate GDP growth.

Digital products have a way of “collapsing” categories of goods and services into fewer items, like the smart phone evaporated scores of products.

On the other hand, there could be some truth to a slowdown in progress. We can't move people into cities, or teach them to read twice, the low hangling fruit may have been picked.

If we taxed long term capital gains at the same rate as income then stock buybacks wouldn’t be meaningfully different from dividends. This generalizes: you should prefer to own stocks that do buybacks and do NOT issue dividends because then you’ll pay less in taxes.

Also you’d get to choose which year to pay those taxes so you can retire much earlier.

For some reason even intelligent people misunderstand this point and so prefer stocks with dividends. But the math works out the same either way: they’re both extracting profits from a business.