Why the postwar prosperity was not atypical

Atypical was an economic policy benefitting ordinary Americans as well as the Elite.

Economic liberals note that real wages for working class people have grown more slowly since the 1970’s than they did before (see Figure 1) and blame the tax-cutting “supply-side” economic policy in vogue since the Reagan administration as responsible for this development. They point to the postwar economy, that saw excellent economic performance despite the presence of things neoliberals argue are bad for growth, like high top tax rates, tariffs, big government (6X growth from pre-New Deal), and restricted immigration.

Lack of foreign competition did not create US postwar economic performance.

Some argue that the post-war era was an anomalous period when America faced no foreign competition from war-devastated countries, giving American industry an advantage that overrode the negative effects of policy. If this were true one would expect trade to have shrunk in importance as a result of the war. Figure 1 shows imports were about the same after the war as they had been before the Depression. Imports did not start to rise until after tariffs were reduced in the mid-1960’s and then exploded upwards two years after the end of the Bretton Woods system as previously detailed. At this point currencies became freely traded.

Figure 1. Imports, Trade Deficit, Tariff, Trade-Weighted Dollar and Unskilled Wage (2017$) trends over time.

After 1973, the dollar first fell as it tried to find its level in the absence of the support it had had under the Bretton Woods system. Imports rose steadily during this time and a significant trade deficit first appeared in the late 1970’s. Real wage growth largely stalled out after 1973. Fed high interest rate policy in the 1980’s made the dollar more attractive to foreign investors and it rose in value, making US exports less competitive and raising the trade deficit. A further round of tariff reductions and the end of the Cold War spurred strong growth in US trade as shown by import growth. Imports grew strongly in both the 1970’s and over 1990-2007, but import growth was largely matched by export growth in the first period, but not the second. The deindustrialization incented by high interest rate policy in the 1980’s and the rising influence of SP culture since then served to make American exports uncompetitive on world markets. It was American policy, not foreign industries’ recovery from WW II, that made America less competitive with our trading partners.

Productivity changes do not explain working class wage stagnation since the 1970’s

Another excuse made for why the US economy over the last half century performs so much worse for the working class than it did in the postwar era is the shift away from high-productivity manufacturing jobs, which can support higher wages. This idea draws on the same logic as the quantity theory of money (QM). QM states that the dollar value of output (nominal GDP) is equal to the quantity of money M multiplied by the velocity (V) of circulation. Nominal GDP can also be represented as the product of real GDP (rGDP) and the price of that GDP. Dividing through by real GDP leaves the price as a product of V and the ratio of money to real output. If one assumes V is constant, price can be affected by changing the money supply. In practice V is not constant and this doesn’t work.

This same logic can also be applied to labor. Here Productivity (P) is defined as dollars of GDP divided by total hours worked (L):

1. P = GDP / L

Some fraction f of GDP is paid to workers for the labor supplied. This is the wage bill W.

2. W = f GDP = f P L

Dividing by hours worked L yields average wage w in dollars per hour:

3. w = W/L = f P

If we see f as constant, then wage is directly related to productivity (the amount of output created relative to the hours employed) which makes the same sort of sense that QM did for prices and money supply. In practice f, like V, is not constant, so equation 3 is not useful. The productivity explanation for the lack of wage growth, assumes constant f, which is why it is invalid.

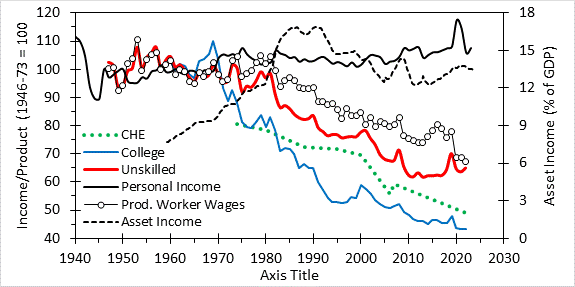

It is approximately true on an aggregate basis. Figure 2 shows a plot of various kinds of personal income, or wages (dollars/hour) divided by output or output/hr (productivity) to give f. The values are relative to their average value in the postwar era which is set at 100. Note that f does seem to be roughly constant for total personal income. Thus, there has been no loss in the transmission of the fruits of economic growth to people’s income. The change has simply been to whom the fruits go. As Figure 2 shows the share going to production workers and unskilled workers has been falling since around 1980. This means that income that used to go to production and unskilled workers (i.e, the working class) is now going other recipients of personal income.

Figure 2. Income relative to productivity for different groups (1946-73 average = 100)

The productivity argument holds that service jobs do not create as much revenue per hour as manufacturing jobs did and so less output is being generated by working class people today and so the pay is less. Added to that is the idea that since technology is responsible for productivity growth, the benefits of rising productivity largely went to more highly educated workers who mastered the new technology. Figure 2 also shows a plot of salaries for college graduates relative to productivity since 1960. This plot shows a stronger decline than the other workers. This decline reflects two effects. One is a compositional effect that was already lowering average wages for this group in the 1970’s, when working class incomes still held up fairly well. The second effect is the same 33% decline seen in the working class wages, showing that “upskilling” by acquiring a college education did not prevent the same lack of wage growth experienced by those not pursuing college.

The compositional effect reflects changes in the kinds of people who obtained college degrees. Before WW II it was mostly the children of elites, who would receive high incomes regardless of whether they had a degree. But as college education became more widespread, college-educated earning power came to resemble that of workers without a college degree. Consider my own field of chemical engineering, which can be considered as a high value STEM degree (it had one of the highest starting salaries in 1980 and still ranks fairly high). By focusing on a single degree that maintained its high-value status, compositional effects can be largely eliminated. Starting salaries posted a rise from $74K in 1974 to $83K today in 2022 dollars but declined relative to productivity shown as the green dotted line in Figure 2. The slope of the decline in productivity-adjusted chemical engineer starting salaries was the same as that shown by wages for production and unskilled workers. This implies that even STEM workers have seen the same decline as everyone else. Yet personal income has not declined. So where is it all going? Some of it is going to owners of assets, who saw their share of output rise from an average of 9.3% over 1959-73 to 15.6% over 1980-2000 and 13% since 2000 (see dashed black line in Figure 2).

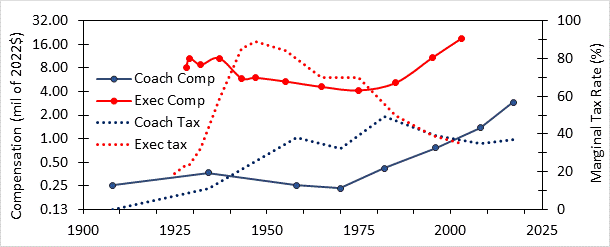

Much of it went to a relatively small fraction of elite workers. As examples of these I chose college football coaches and corporate executives. Figure 3 shows a plot of income, adjusted for inflation and economic growth using per capita GDP. This adjustment serves a similar function as the calculation of f values in Figure 2. For example, the chemical engineer starting salaries that saw declining f in Figure 2 would show a 28% decrease in Figure 3. This decrease for STEM graduate income is compared to a 365% rise for executive income.

I selected coaches as an example because we have a direct measure of their productivity—their win record. A more productive coach is one who wins more games than they lose. A less productive one loses more often. The average or median coach necessarily wins half of their games and does so every year. They have a constant productivity. The only thing that can affect their compensation is the value of f, the amount of economic output that goes to them rather than some other kind of worker. It is clear that f has risen for coaches and executives from much lower levels during the postwar era, while it has fallen for most workers.

Figure 3. Compensation (adjusted for inflation and economic growth) and marginal tax rates over time.

Some factor, present in the postwar period but absent since then, served to keep f high for ordinary workers and low for elite workers. I believe that factor is the economic culture as proxied by economic inequality. A key feature of the onset of the stakeholder capitalism (SC) culture* created by New Deal policies was wage compression, which translated into rising real wages for the working class and declines in real income for executives and coaches and probably other highly compensated people.

Executive compensation plays a key factor in economic cultural evolution. A business book whose title I do not recall taught me, “you get the behavior you incent.” That is, the behavior that leads to higher compensation encourages more of the same behavior. For executives who derive most of their compensation from stock options, what is incented is efforts to raise stock prices such as those I discussed in my last post. Behavior of this sort is characterized as shareholder primacy (SP) culture.*

So how did is come to pass that SP became a thing? Unlike ordinary workers, top executives collectively set their own compensation because they tend to sit on each other’s boards, although shareholders do have a say. As I described previously, shareholders’ interests and the high-top tax rates present before 1981 discouraged high executive compensation, so we do not see a rise in f for this group until after the 1981 tax cut. Figure 3 shows the marginal tax rates seen by executives and coaches. During the entire period of the New Deal Order (1933-80) the tax rates executives faced were much higher than what the coaches ever faced. The marginal tax rates for coaches before 1981 were not at a level where they affected their compensation demands. As Figure 3 shows, coach salaries had already recovered to their pre-income compression levels by the time tax rates were dropped in 1981. Clearly a culture more permissive of outsized compensation for some (the beginnings of SP culture) was already forming in the early 1970’s. Because this culture were already present when tax rates fell, executives felt comfortable with voting themselves real compensation far beyond anything their predecessors had earned. But the executives’ decisions affected how they ran their businesses, which affected how the economy evolved, creating the financialization and shareholder focus characteristic of SP culture.

SP culture arose when the combustible mixture created by the flawed economic policies of the Kennedy-Johnson Administrations met the spark of radical conservative economic ideas. The 1960’s and early 1970’s were a creedal passion period (CPP) like now, a time when radical ideas flourished. Along with sex, drugs, rock n roll, and the radical Left, the Right saw Barry Goldwater’s “extremism in defense of liberty is no vice,” the “go-go” years in the stock market, the Powell memo, and the founding of the Libertarian Party. CPPs flare up every fifty years or so. Pre-existing radical ideas suddenly catch on. In this case the ideas behind the radicalism on the Right had begun to be promulgated as early as 1947 but had to wait for the CPP to take shape. Goldwater was soundly defeated, and had Democrats taken the threat he represented more seriously and acted to defend rather than discard the New Deal Order they created, he might have remained a joke like his fellow CPP creation, George McGovern.

The shared prosperity of the postwar economy and the New Deal Order that underlay it were the product of the SC economic culture that preceded today’s SP culture. For SC culture, the stock market crash and subsequent depression provided the combustible mixture set alight by Progressive ideas promulgated during the Progressive era CPP. I provide an account of how the Roosevelt administration applied these ideas to secure the political power needed to do more. This Substack post provides a ground-level account of one of these early efforts at establishing SC culture made in tandem to the Roosevelt administration’s policies.

The Progressive Era CPP saw the development of some of the ideas and tools (e.g. Income Tax) used by New Deal reformers. Radical Marxists active during this same CPP were crushed by the 1919 Palmer Raids and socialist ideas began to decline after reaching their maximum appeal during the CPP. By the time of the 1932 election the unworkable ideas on the Left had largely been eliminated leaving the more pragmatic (but still radical) ideas for the New Deal policymakers to consider.

The New Dealers took some of these ideas and implemented them in a way that both changed how the economy operated for their working-class base and created a durable political coalition that gave them electoral victories for decades. I believe a new generation of reformers could do something similar today, if they had the opportunity provided by economic crisis and the right set of ideas, The 2008 financial crisis provided a suitable opportunity, but the ideas were not there in either party. Perhaps the current CPP will see development of suitable ideas for such a purpose. This substack is my own contribution to such an effort.

*A different account of culture evolution showing how the idea of shareholder primacy is more than 90 years old is given here.