A potted history of shifts in the economic experience over the past 60 years

There was a time when my parent’s generation were in their rising adult and middle phases of life when the economic experience for ordinary people was positive, and a concept called the American Dream became part of the culture. Ordinary working- and middle-class folks saw tangible improvements in their living standards that occurred in real time. The reason for these conditions was an economy that operated under what I call stakeholder culture (SC). Though remnants that economy persisted to the end of the last century, it is now long gone. The stakeholder culture was gradually replaced by a culture I call shareholder primacy (SP). These cultures are the result of a cultural evolutionary process taking place in an economic environment established by government policy.

The primary cause of the shift in the economic experience and the culture were three changes in government policy. First was a choice to abandon balanced budgets and retention of the national gold reserve in the 1960’s. Second was a decision to end gold exchange and resort to explicit economic controls to manage inflation: price controls over 1971-73 and extreme interest rates beginning in 1979. These policies greatly weakened the labor movement and began the shift away from stakeholder culture in the late 1970’s. The third change was the decision to take advantage of inflation suppression by high unemployment to enact of program of tax cuts and policy changes such as legalized stock buybacks (what I call neoliberalism) that were inimical to worker interests. Neoliberal policy accelerated the shift to shareholder primacy and played a major role in the financialization of the economy. These things have led to massive growth in financial wealth and an increased chance of financial crisis.

Following Gary Gerstle, I divide recent American history into two periods, the New Deal Order before 1980 and the Neoliberal Order after. I believe these periods closely correspond to Stephen Skowronek’s political dispensations. Stakeholder culture and the New Deal Order were the product of the FDR dispensation, while shareholder primacy and the Neoliberal Order came from the Reagan dispensation.

We can summarize neoliberalism/SP culture/Reagan dispensation and New Deal/SC culture/FDR dispensation as the policy for Winners and Losers,1 respectively. Neoliberalism made possible by the Reagan dispensation has allowed for an increased number of winners in society. Associated with Winners policy is a greater number of losers, illustrated by lack of wage growth and the rise in the homeless population in the 1980’s as neoliberalism took hold.

Figure 1. Income trends for different classes relative to their levels in 1947

Income gains by economic class shows impact of pro-Losers vs pro-Winners policy

Homelessness scholar Don Mitchell notes that “the U.S. economy was organized differently from the New Deal until 1973…Capitalism was organized in a way that was less mean than it is now.” This “less mean” way capitalism was organized was the product of stakeholder culture. It provided a more favorable outcome for those less well off. Figure 1 illustrates this by comparing the trend in income levels for four income classes: rich (top 1%), affluent (next 9%), middle class (next 40%) and working class (bottom 50%) for the period since WW II. The trend for the rich is flatter in the period before 1980 than after, while that for the working class and middle classes was steeper before 1980. The trend for the affluent has been about the same throughout the entire period.

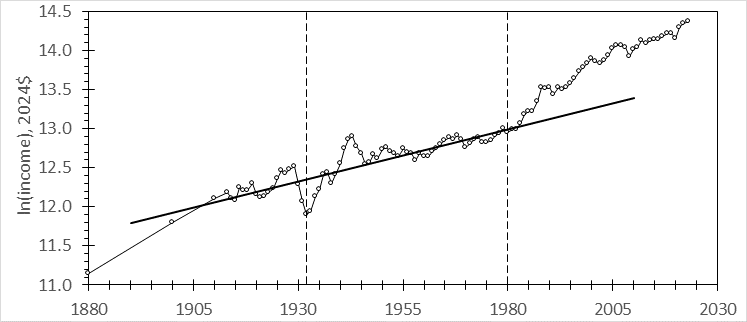

Figure 2. Rich income (defined as 100 x GDPpc x top 1% income share) since 1880

Additional insight is achieved by looking that the trend over longer periods of time. Figure 2 shows the trend in income for the rich (defined as the top 1%) since 1880. The graph is divided into three periods reflecting the political dispensations in force: before 1932 (McKinley-Roosevelt dispensation), 1932-1980 (FDR dispensation) and after 1980 (Reagan dispensation). During the FDR dispensation trend growth rate for the rich was only 1.3%, compared to 2.5% before and 3.0% after. This lower trend made the accumulation of extraordinary wealth difficult. The only people able to reach into modern levels of extreme wealth were obsessive freaks, such as the miser JP Getty (who refused to ransom his grandson when he was kidnapped), Howard Hughes (who kept his urine in jars) and bigamist crank HL Hunt (called stupid by President Eisenhower).

Figure 3. Working class income (2 x GDPpc x bottom 50% income share) since 1880

Figure 3 shows the income trend for the working class (defined as those earning less than the median income). The trends for the various periods are the opposite of those for the rich. During the FDR dispensation, growth in working class income was about 3.1% compared to lower rates of 1.2% before and 0.8% after. This dramatic change in their economic fortunes formed the basis for the Democratic working-class coalition created by FDR and his fellow New Dealers. I have previously described how Roosevelt initially forged this coalition and how the New Dealers “locked in” the allegiance of a generation of working-class Americans through the dramatic increase in the living standards for the American proletariat during WW II. After the war the good times continued until it began to slow in the inflationary 1970’s. I believe inflation played a major role in slowing growth in the 1970’s. Inflation distorts the price signals on which a market economy operates, which is why low inflation is also preferred. As I discussed in a recent post, 1970’s inflation can be explained through a quantity of money-type analysis, meaning that the failure of Democratic policy makers to run balanced budgets played a major role in the 1970’s slowdown and the end of the FDR dispensation. This failure has led to a gradual bleeding of working-class support for Democrats which is essentially complete today.

Figure 4. Middle class income (defined 2.5 x GDPpc x 51-90%tile income share).

Figure 4 shows the income trend for the middle class (defined as those in the 51st through 90th percentile of incomes). It is similar to the trend for the working class, just less extreme. Growth rate under the FDR dispensation ran at about 2.6% compared to 1.0% before and 1.3% after. Growing up under the FDR dispensation, I lived on a block in which down the street lived my best friend, whose father was a corporate executive at a mid-sized company. Across the street from him lived two more of the kids we grew up with, whose father was a truck driver. Also on my block were a mix of social workers, professors, schoolteachers (like my dad), an owner of a paving firm, a cop, a CPA, an engineer, lots of retirees, and others. People from different economic classes were mixed together. All us kids grew up together, played together as kids and drank illicitly together as teenagers, oblivious to the class differences that separated us, because they were not that great.

Figure 5. Affluent income (defined GDPpc x 91-99%tile income share divided by 0.09).

Curiously, the trend for affluent workers (those in the 91st through 99th income percentiles) does not show substantially different trend growth rates under the various dispensations. Figure 5 shows the data for the 1910-2023 period is reasonably consistent with a single trend growth rate of about 2.2%. When one considers that the affluent class provides most of the societal managers it makes sense that the society they manage would provide a fairly consistent growth track for them. The different outcomes for the other economic classes then come from the kind of societal management the affluent class provides. During the first and third periods in Figures 2-5, they managed society on behalf of the rich in order to produce results favorable to rich (and themselves). During the New Deal Order they managed things in favor of the working and middle classes (and themselves).

The affluent class and the rich comprise the group I think of as the elites. I previously wrote about this group here. Elites with different political ideologies or objectives join political parties in which they express or pursue their economic and cultural beliefs or interests. There are Democratic and Republican elites. Emancipation stripped the slave wealth and elite status from many of the antebellum Democratic elites. After the Civil War, most of the rich elite were Republican Northerners. They and their affluent elite allies ran the economy and the government most of the time for the 1865-1929 period. They comprise the group I call the Capitalist Elite. Unlike the Republicans, Democratic elites had relatively few rich members, so when they came to power in 1933, they were free to craft a crisis response that screwed over the rich (see Figure 2). Their policies were designed to benefit the largely immigrant, working-class urban citizens who formed their political base in the North, as well as new working- and middle-class voters whose support had given them the power to enact the New Deal.

The politics of winners and losers today

Today the situation is quite different. The managers of the New Deal became members of the establishment and many of them or their heirs became rich. They and other Democratic affluent class members constitute the group I call the Mandarins, the Democratic counterpart to the Capitalist Elite. Today the rich are distributed fairly evenly between the two parties, and this fact shows in the 83:52 split between Democratic and Republican billionaire supporters in the 2024 election.

Dan Williams briefly discusses an Economist article titled “Are British voters as clueless as Labour’s intelligentsia thinks?” as follows:

[the article] observes a recent strain of “nihilism” that has “infected” the experts and advisors to the United Kingdom’s Labour Party in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s presidential victory…According to this nihilistic stance, the project of “deliverism”—trying to win elections by delivering outcomes that materially improve people’s lives—is dead. Joe Biden’s presidency delivered. The economy performed well. The government intervened on behalf of the most disadvantaged members of society. And what did the Democrats get for it? Donald Trump.

Close examination of Figure 1 shows that while all classes made gains under both Biden, the rich gained the most. By other measures the case that Biden delivered to working people more than Trump did is similarly murky. I direct the reader to focus on the WW II period between 1940 and 1945 in Figures 3 and 4 and then compare them to Figure 5, noting the size of the income jump as one goes from working class to middle class to affluent. As you move up the class hierarchy, the positive wartime effect gets smaller. As I wrote here this policy was deliberate:

Strong growth with minimal inflation was accomplished during WWII via wage and price controls through the National War Labor Board (NWLB) and the Office of Price Administration. The New Dealers designed wage policy so that increasing the wages of low-income workers was easier than increasing wages of high-income workers… The policy was successful, significant wage compression was achieved.

Nothing remotely similar to the worker gains achieved by the New Dealers during the war and the extension of these gains for three decades afterward has been achieved since the New Deal Order ended. The reason why the working and middle classes (Losers) did so much better under Democratic policy than Republican policy is simply that the Democratic elites that implemented it were Losers. They had lost the Civil War and their economic (rich) elites as a consequence. This made them in the postwar period little more than a party of reactionaries holding a grudge. Over time they built a Northern constituency among immigrant/ethnic working-class people to add to their reactionary base. The strategy was enabled by Republican xenophobia inherited from their “Know Nothing” forbears, which remains as part of Republican political DNA to this day.

Democrats had elite leaders, but these were political elites, who drew their status from political achievements. Democrats lacked elites whose status came from economic achievements. Thus, New Deal Democrats were capable of acting in ways that were anathema to the economic interests of rich people, because their elites cared more about winning the politics than economics. They were free to embark on policy (e.g. high taxes, fiat currencies) that economic dogma said would lead to poor economic outcomes, and got the opposite, showing that economic dogma isn’t always right. Yet this same sense of placing politics over economics doomed the New Deal order, when 1960’s Democrats rejected fiscal conservatism, as they had once rejected the gold standard.

Today’s Democrats were the winners of the previous secular cycle crisis resolution and got the chance to build their own Novus ordo seclorum. They became both economic and political winners and could no longer easily embrace a “Loser strategy” for this cycle. They continued to feel an ownership and responsibility of “the postwar system” their forebears created, even as Republicans have dismantled more and more of it. For example, when faced with a potential collapse of the financial system in 2008 (which would be very harmful to Republican wealth holders) Democrats felt they had to vote for the Republican TARP plan, when Republicans would not, rather than let the consequences of Republican policy play out. Democrats in 2021 could not pass the tax increases that might offset the inflationary impact of their stimulus bills because of Democratic opposition to tax increases on the rich. Democrats today celebrate the role of their billionaires against the other side, even though these billionaires can change sides on a dime.

The Republicans and the Whigs before them were the party of the rich, operated by the capitalist elite and serving the interests of rich capitalists. They have always been a Winner’s party. By making the world’s richest man the architect of his administration’s domestic policy, President Trump has made it clear he does not plan to deviate from this script. So, what we have had since the rise of the Reagan dispensation is no party who operates in the interests of losers. So, who do the Losers (90% of the population by my definition) vote for? Since neither party offers policy that benefits their material lives, they vote for whoever appeals to them on cultural issues. At present this is Donald Trump and the MAGA Republicans.

Losers are the bottom 90% of income earners, who have lost ground economically compared to the Winners (top 10%) since 1980.

Yes, this is my assessment as well. The working class went for Trump because he offered disruption not populism. For people who have given up and see no one in their corner, blowing it all up has a mighty appeal.

The Reagan administration was not a genuine project of decentralization but instead a masterful exercise in political and economic centralization under the guise of deregulation and free-market rhetoric. While it used language of shrinking government, in practice, it selectively dismantled regulations that inhibited corporate consolidation while reinforcing federal power in ways that favored economic centralization. The airline deregulation authority, for instance, actively prevented local areas from subsidizing their airports under the supposed ideal of no "market interventions" while deeply hypocritically working with the localities where the newly cartelized industry wanted to place their hub-n-spokes to subsidize them there, effectively destroying smaller regional hubs and further concentrating economic activity in select national centers, they, in effective terms, acted like something not to far off from a soviet industry planning organization for the airline industry and used the awesome powers of the federal government to do it. And thats far from the only area they did that. The administration's industrial policy was just as real as anything Walter Mondale proposed, but it was carried out through defense contracts, financial deregulation, and selective market interventions that empowered large corporations while gutting regional economic diversity. It was not the absence of industrial policy, it was centralized industrial policy that masked itself as its opposite. In fact, the Bayh-Dole Act, in practice, may be at once one of the most centrally directed and resource intensive AND harmful industrial policies ever implemented.

Also, your statement towards the end regarding Republican Party having always been simply a tool of the rich and a disguised continuation of the Whigs is wrong and it retrojects the modern Republican Party’s structure and interests onto its pre-WW2 incarnation, ignoring the fact that, until the mid-20th century, the Republican Party was fundamentally a small "r" republican party, not a conservative party in the modern sense. While it had pro-business tendencies, it was not simply a vehicle for capitalist elites but a genuinely decentralized mass-member party with strong regional and ideological diversity, including progressive, moderate, and conservative factions. Unlike today’s highly centralized parties, the pre-WW2 Republican Party had robust state and local structures, often operating independently with meaningful internal contestation. Even during the Gilded Age, its policies were shaped by a complex interplay of industrial, agricultural, and reformist interests, rather than being a monolithic tool of "the rich." This decentralization allowed for significant internal competition and ideological shifts, as seen in figures like Robert La Follette, who led an influential progressive insurgency within the party. It was only after World War II, and especially with the rise of the Neoliberal Era, that the party transformed into a more rigidly structured vehicle primarily serving corporate and elite interests, losing its prior decentralized, mass-member character.