How the New Deal Order fell

The economic policy decisions leading to the shift from the New Deal to Neoliberal Order

There has been a growing feeling that something is wrong with the direction America is heading since the turn of the century. The idea that we live in a time of crisis has gained currency in recent times. America in Crisis is an analysis of the political and economic dynamics responsible for this feeling. I use a cyclical concept, not William Strauss and Neil Howe’s generational cycle referred to in the previous link, but Peter Turchin’s secular cycle, with corrections that address some of the issues raised in the cited review. I believe a major driver of society is cultural evolution and talk about it a lot. There is also quite of bit of political, economic and financial discussion as I believe these disciplines are also very important to understanding what is going on. I wrote up my analysis in a book with the same name as this substack. I cover some of the material in the book here, plus new insights as they occur to me. For easier comprehension it may help to read posts in sequential order so that when an older post is referenced there is some familiarity.

In my last post I noted the causative role SP culture plays in problems such as the failure of wages to keep up with productivity growth, the inability to build the infrastructure needed to address climate change, or financialization of the economy and the instability it breeds. During the postwar period, when SC culture was in force, a period historian Gary Gerstle calls the New Deal Order we did not have these problems. SC culture changed to SP (and New Deal Order shifted to Gerstle’s Neoliberal Order) as a result of choices government policy makers made during the 1960’s through 1980’s. The post describes how this happened.

Elite acceptance of the New Deal paradigm started to break down during the 1960’s. The first clear evidence for this was President Kennedy’s call in the 1960 campaign for what would be called a “supply side” tax cut today. Between the time the tax cut was proposed (1962) and enacted (1964) US troop levels in Vietnam more than doubled to 23,000. Enacting a tax cut at a time the country was embarking on another war had never previously been done. In the year after the tax cut, troop level increased eightfold, yet the tax cut was not repealed.

The result of these policies was a rise in inflationary forces that were incompatible with the Bretton Woods system, which was still indirectly based on a gold standard. We can see how this happened using the money balance model of inflation. Over 1949-57, unemployment had averaged 4.3% while Balance had been negative (–0.18), for which the NAIRU was very low--about 4.0%. As a result, average unemployment rate was high relative to the NAIRU associated with the money balance, giving a low inflation rate of 1.6%, This situation represents ideal conditions for the operation of SC culture and represents the high point of the New Deal Order. After 1957 the situation changed abruptly. Balance shifted upwards to an average value of +2.4 over 1958-64, giving a higher NAIRU value of 5.3%. Inflation was even lower at 1.4% during this time, but at the cost of a higher-than-NAIRU average unemployment rate of 5.8%. The money balance (Balance hereafter) averaged +2.3% over 1965-70, maintaining NAIRU at 5.3% for the rest of the decade. Average late sixties unemployment of 4.0% (now well below NAIRU) led to an average inflation rate of 3.8%, more than double the average for the previous 15 years. This analysis shows how the policy choices described in the previous paragraph translated into the inflationary forces that would dominate policy choices in the 1970’s leading to the collapse of the New Deal Order.

Of course, one does not know values for Balance or NAIRU in real time so the above analysis showing the New Deal system coming under an inflationary threat after 1957 could not have been made at the time. There was, however, another tool that was available, the US gold reserve. The US was the only major belligerent to finish WWII in better economic shape than it had entered the war. As a result of this economic strength, it had accumulated a vast gold reserve, which amounted to about 9% of GDP in 1949. It was used to back the dollar in the Bretton Woods dollar-reserve system. Figure 1 shows a plot of US gold reserves and cumulative fiscal balance over 1949-1971. The correlation between declining gold reserves and cumulative government deficits is clear.

Figure 1. Gold reserves and federal fiscal balance 1949-1971.

The trend in fiscal deficits mirrors that of Balance. Over 1949-57, average values of Balance and deficits were –0.18% and +0.06%, respectively, while over 1958-70 the corresponding values were +2.3% and +0.7%. Deficit levels increased twelvefold, Balance shifted from negative to positive, and NAIRU went up 1.3 points from 4% to 5.3%. While the 3.7% unemployment minimum for the 1954-57 expansion was just 0.2% below NAIRU, the 3.4% unemployment rate at the end of the 1961-69 expansion was 1.9% below NAIRU. The difference between these two periods was the 275 basis points of tightening needed to check rising inflation at 3.6% in the late fifties compared to the 800 points of tightening needed to stop inflation at 6.4% a decade later. That the noninflationary fifties were transforming into an inflationary sixties was clearly indicated in Figure 1. The flat profile in gold reserves was followed by a declining trend after 1957, signaling this transition in real time. And the cause (deficit spending) was also clear.

The ruling Democratic party did finally get the memo, and belatedly passed a one-year surtax in 1968, resulting in a budget surplus in 1969, which produced a corresponding rise in gold reserves. President Nixon, a lifetime monetarist, who had opposed Kennedy’s proposed tax cuts in the 1960 election, could have sought a continuation of the surtax in 1969 and raised the gold-dollar exchange rate to $42 (reflecting commodity price appreciation since the beginning of the gold drawdown), in an attempt to reverse the damage wrought by a decade of fiscal irresponsibility. He did not, deciding instead to embrace the economic principles of his political opponents, despite the rising inflation and interest rates they had created. By mid-1970, inflation had peaked and unemployment was rising. Nixon sought and received authorization for wide-ranging authority “to issue such orders and regulations as he may deem appropriate to stabilize prices, rents, wages, and salaries at levels not less than those prevailing on May 25, 1970.” Nixon, desiring reelection, and aware of the outcome of austerity for President Hoover, mentioned in January 1971 that he had become a Keynesian in economics, meaning he would not be trying to balance the budget to address the inflation problem.

Figure 2. Inflation, unemployment and short term interest (ST) rates, along with Balance and NAIRU 1925-50

Nixon apparently saw the potential of wage and price controls like those used during WW II to reduce inflation despite high budget deficits. Nixon’s anti-inflation program involved an import surcharge and suspension of gold-dollar convertibility in addition to price controls. Nixon’s Keynesian turn saw a Balance value around +6 over 1971-72 , which remained at this level for the rest of the decade. This shift upwards meant a new NAIRU of 6.6% was now in force. The higher NAIRU meant unemployment levels would need to be maintained above 6.6% (i.e. at recession levels) if inflation was to fall. As happened in WW II (see Figure 2) the controls suspended the effects of NAIRU, allowing unemployment and inflation to fall together. Unemployment had reached 6.1% at the time controls were announced, while inflation stood at 7.6%. By election day 1972, inflation was down to 3.2%. Unemployment began to fall immediately after Nixon’s policy was announced, was down to 5.3% on election day, and would fall below 5% by inauguration. Nixon’s price controls worked; he was re-elected in a landslide.

Price controls are a temporary fix. The underlying problem was the strongly positive Balance and associated high NAIRU. Prices controls worked well in WW II because after the war, taxes remained at near wartime levels while military spending plummeted, resulting in a shift in Balance from a massively positive to negative over 1946-48 during which NAIRU fell from a level higher than the unemployment rate in 1946-7 (resulting in high inflation) to a value around the same as the unemployment rate in 1948 (giving falling inflation--see Figure 2). Nixon did not raise taxes to post-WW II or Korean war levels, or even restore the surtax in 1973, so Balance remained high and NAIRU with it. Unemployment remained more than 1.5 points below NAIRU over all of 1973, over which time inflation rate rose by six points! Over the first nine months of 1973, commodity prices were on a tear, rising at an 18% annual rate. Such an environment provides an opportunity for commodity producers like the OPEC nations to demand (and get) much higher sustainable prices. When expressed in terms of gold, the real price of oil had fallen in half since dollar-gold convertibility had ended. There was good reason to believe that the effects of the Arab oil embargo in October 1973 would be a permanent increase in oil prices (and revenues) for OPEC members. After the start of the embargo, commodity prices rose at a 22% rate over the next year, while oil prices were up close to four-fold, and never fell from that level going forward.

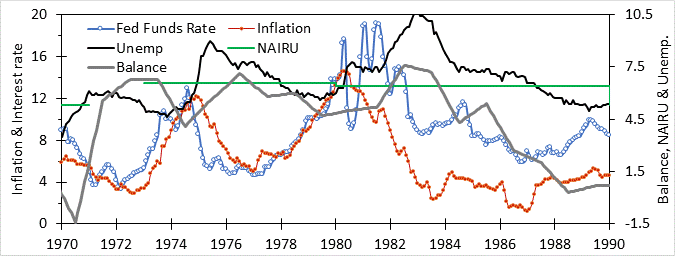

Figure 3. Inflation, unemployment and short term interest (ST) rates, along with Balance and NAIRU 1970-90

Inflation in the US remained consistent with the Balance model. Consumer price inflation continued to rise until it reached a peak of 12.2% in November 1974, at which point unemployment reached the NAIRU value of 6.6%. Inflation began to subside while, with the economy deep in recession, unemployment would continue to rise, peaking at 9% in May 1975 (see Figure 3). Inflation subsided to a 6-7% level while unemployment slowly declined. When unemployment fell below the 6.6% NAIRU at the beginning of 1978, inflation began to climb from the 6.1±0.6 percent level it had been for the previous two years to much higher levels. Inflation rose 2.3 points in 1978 and 4.3 in 1979 before peaking at 14.6% in spring 1980. To stop inflation from rising further had required 1300 basis points of tightening. A trend is clear, to stop rising inflation in the late 1950’s, late 1960’s, early 1970’s and late 1970’s had required steadily increasing interest rate increase: 275, 800, 960, and 1300 basis points, respectively. It was clear that an inflation monster had been created, which required another 150 basis points of tightening (on top of the 1300) to finally slay. Doing so resulted in the creation of a “permanent recession” with unemployment remaining above NAIRU (average 8%) for seven years until the start of 1987, when unemployment finally reached 6.6% at which time inflation reached its cycle-low of 1.2%. After this, unemployment continued to fall to 5.2% in June 1990, over which time inflation nearly quadrupled to 4.7%, on its way to a 6.4% peak in October. The 1980’s expansion spelled the end of the US labor movement as a significant economic actor, Real unskilled wage levels were down 8% over the decade, a period conservatives laughably call the seven fat years.

Maintaining high unemployment over most of the 1980’s not only destroyed Labor, it also permitted low inflation to co-exist with large deficits arising from massive tax cuts on the wealthy, which was a key plank of “Reaganomics.” As Dick Cheney would later put it, “Reagan proved deficits don't matter.” The theoretical justification for this policy was something called “supply-side economics”, which appears to be a conservative-friendly rebranding of Nixon’s Keynesianism. According to my cultural evolution model, the evisceration of Labor and reduction in top tax produced the shift from SC to SP business culture and in their respective political manifestations as The New Deal and Neoliberal Orders.

The economic model introduced by the New Dealers placed responsibility for managing the economy on the elected President and Congress—not the Federal Reserve, as is the case today. That the system was breaking down was clearly evident by the ominous decline in US gold reserves depicted in Figure 1 and the lack of action to address it. Rather than deal with this threat to the monetary system on which postwar economic success rested, Democrats opted to cut taxes and embark on an unnecessary war. Prior to the war, the Kennedy-Johnson administration had spent much more on the military than did the Truman or Carter administrations during peacetime. Had they emulated these other Cold War Democratic administrations, the savings would have amounted to more than $80 billion dollars by 1965. Figure 1 suggests this would have reversed the outflow of gold. Balance might have shifted back to its 1950’s value and NAIRU would fall, preventing inflationary forces from building. President Johnson had big plans for domestic spending with his War on Poverty program, which he pursued, resulting in more than 30 billion dollars of deficit spending. Yet, had Johnson eschewed getting entangled in a pointless war and spent on the military like other Democrats during peacetime, he would have saved $90 billion, more than enough pay for his social programs and eliminate the deficits that were emptying Fort Knox. But this did not happen. Rather, Johnson chose to pursue Kennedy’s tax cut, the Vietnam war, and his social programs.

Irresponsibility continued with Nixon’s refusal to deal with the gold outflow by raising taxes or renewing the surtax. He sought the easy way out, ending gold convertibility and implementing price controls to delay bad effects until after his reelection. Their removal began a 14 year period when either unemployment was at recession levels or inflation was rapidly rising, all because of continued high Balance due to a Congress and President unwilling to handle the responsibility of managing the economy. It was called stagflation and seen as a new thing, but it was consistent with the Balance model and nothing new. Jimmy Carter, the last adult in the room, correctly eschewed price controls and sought to reduce the budget deficit. He called for doing so through spending reductions, which was not realistic, higher taxes would have been required as well in order to get Balance down to a level where NAIRU would become sufficiently low so that inflation would not immediately develop as the economy recovered from the 1973-75 recession. In the end Carter appointed Paul Volcker as Federal Reserve chairman, who intended to crush inflation with permanent high unemployment. This decision was the death knell for the New Deal Order, though its demise had been foreordained by Kennedy and Johnson’s lack of attention to declining gold reserves.

The discussion above shows the difficulty presidents have in raising taxes. This has always been a case. A article in Colliers Magazine, months before the 1932 Revenue Act was passed, quoted a child’s riddle to express the difficulty of raising taxes in a democracy:

Congress! Congress! Don't tax me,

Tax that fellow behind the tree.

The 1932 Revenue Act would end up raising the top rate from 24% to 63%, and form the foundation upon which SC culture (and New Deal Order) was built (see Figure 4 here). It was President Hoover, not FDR, who began this transition. Similarly, by appointing Volcker as Fed Chief, it was Carter, not Reagan, who was the father of the Neoliberal Order. As described in section 4.1 of America in Crisis and in a previous post, a connection between deficit spending and inflation was believed to exist. This connection is a limiting case of the more general Balance model that neglects financial flows, which in the modern economy are dominant. Because of the long-established difficulty in raising taxes implied by frequent iterations of the rhyme over time, Kennedy ought to have understood the risk he was taking by proposing a tax cut in the 1960 election and then actually proposing it to Congress in 1962. Once taxes are cut, they can never be uncut in the absence of a war or similarly serious crisis. It is true that the economy was in a serious recession in 1960. But this can be dealt with by short term stimulus spending as Keynes had recommended. Indeed, a major infrastructure program was enacted by the Kennedy administration, which seems to have worked, unemployment which peaked north of 7% in the early months of his administration was down to 5.5% a year later. A tax cut in 1962 was unnecessary for economic recovery.

The key issue was prioritization. The New Deal Order was not the only legacy Kennedy inherited from his New Dealer predecessors, there was also the largely unfinished extensions of the New Deal proposed by Truman as the Fair Deal and the Truman Doctrine in foreign policy. Johnson’s Great Society addressed the first legacy with initiatives like Medicaid, Medicare, student aid, and the War on Poverty. The Truman Doctrine called for the US to give support to countries or peoples threatened by Soviet forces or Communist insurrection. Examples of this doctrine include the Marshall Plan, as well as aid to Greece and Turkey. Both were successful. Later expressions involved US support for the French in Indochina and then to the Republic of Vietnam. It was this latter issue that was under consideration in 1960. The “domino theory,” which seemed valid in halting Soviet expansion in Europe was now to be applied to Indochina. Without American assistance it seemed likely that all of formerly French Indochina would become Communist.

Honoring each legacy was expensive, and fiscal deficits were already depleting the US gold reserve. In a 1965 New York Times article, author Tom Wicker framed this choice as a debate between “guns or butter.” The debate was not whether the expanded role to be played by the United States in Vietnam was appropriate; there was an unstated presumption among all of the political leaders that the Vietnam War was necessary. There was no question for Republicans like House Minority Leader Gerald Ford, who urged President Johnson to “take the lead in cutting back new domestic programs to marshal the nation's strength for the military effort." It was easy for Republicans to advocate for prioritizing military spending (which benefitted Republican interests) over social spending (which helps Democratic constituencies). Democrats, for their part, did not wish to follow Ford’s advice. Yet there was a real choice that needed to be made. Already before Kennedy’s tax cut and the start of the Vietnam war in 1964, the trajectory of gold reserves was clear, the US would run out of gold in the next decade and there would be a serious inflation problem unless the fiscal deficit was closed. If policymakers wanted to avoid this outcome, the country could not continue its expensive policy of containment (and certainly could not embark on a war) without more revenue. Not only that, but it could not afford expansion of the welfare state without revenue increases or corresponding reductions in military spending. Democrats chose to pursue both the war and the Great Society and let the New Deal Order collapse.

I doubt anyone at the time saw this choice as clearly as observer with 60 years of hindsight can, but the tale told by the gold reserves was a telling signal. President Kennedy could have noted that America could not be strong on all fronts and a strategic withdrawal from Indochina was prudent in order to stop declining gold reserves. In this he could allude to the example of the Roman emperor Hadrian, the third of the “five good emperors,” who withdrew from recently conquered Mesopotamia and built a defensive wall across Britain rather than trying to conquer the whole island. Had this happened, the resulting surpluses would have begun the restoration of the gold reserves. Using a chart of the gold reserves the president could draw a direct connection between a full gold reserve and US economic strength, upon which true national security rests. By doing this he could make toying with the gold reserve politically untouchable by making clear that any new spending or tax reduction must come from either budget surpluses, new taxes (as Social Security was and Medicare would be) or be accompanied by dollar-for-dollar cuts in other (i.e. military) spending. Such a policy was necessary in order to keep Republicans acting as real fiscal conservatives (and not the fake ones they became after they embraced “voodoo economics” in 1980).

But this did not happen. The reasons why will be addressed in a future post.

Please show all the curves for the important period between 1950 and 1970, not just gold and Fed fiscal balance. Thanks!

Intelligent, detailed post. Much more substantive than most of the history I read on this era. There are a few more influential factors from this era that deserve consideration: (you may have addressed them in other posts, but I haven't got that far, so forgive me if I'm bringing up redundant material.)

1) the moves that began during the Carter administration era of the late 1970s to abolish state prohibitions on usurious consumer credit card rates, which were finally upheld by a Supreme Court decision. I don't have all the details from memory, and don't have the time to direct you to specific cases, Congressional bills, or the relevant Supreme Court decision. But beginning around 1980, this inaugurated a whole new era of consumer credit, and consumer debt and debt service. Unprecedentedly easy credit, extended to the American public at unprecedentedly high interest rates. Some of the first interstate card issuers were the Savings and Loan institutions that eventually collapsed in the late 1980s, leading to a cascade of Federal bailouts and bankruptcies by both the S&Ls and their private business debtors. The first mass-market consumer credit cards were very often sent unsolicited via mass mailings to residential addresses. The annual rates offered ranged between 14%-18% per annum. Even after the collapse of the S&Ls, commercial banks were offering unsecured credit cards up front or with instant application at around 18%, often with cash loan "checks" attached (featuring a somewhat higher interest rate, often around 23%.) If I recall correctly, this ultra-easy credit situation abated by the late 1990s. But it may have continued into the 2000s. I don't notice that easy preapproved access solicitation nowadays.

2) the oil shock, of course. The ramping up of already strong OPEC pressure that escalated oil prices during the Carter administration. The snafus around energy policy that basically foreclosed the alternative of nuclear power generation in the aftermath of the Three Mile Island reactor crisis (more of a near miss than an actual disaster, but one that was sufficient to marshal the antinuclear power movement to shut down the TMI and stop any planned expansion of nuclear power plants.)

3) the fact that Carter's attempts to rein in Congressional earmarks and carve-outs were met with massive opposition by his own party in Congress, at a level that practically assumed the dimensions of a revolt. The Congressional Democrats were so dominant in both Houses that the domestic spending programs of LBJ's Great Society had degenerated into a huge pork barrel, and no one in either party was interested in cleaning house. Particularly the Democrats, with their supermajoritarian (or nearly so) power in both Houses. They were only roused from their complacency in order to clash with Jimmy Carter over his attempts to establish a modicum of discipline in some domestic spending programs. The Congressional Democrats proved much more amenable to cooperation with Ronald Reagan's spend-and-borrow policy. The first administration to raise the national debt into the trillion-dollar territory.

The best resources I've found on the institutions of American power and their economic and political transformations of the1970s and 1980s:

The Politics of Rich and Poor, by Kevin Phillips

America: What Went Wrong?

America: Who Really Pays The Taxes?

America: Who Stole The Dream? all by Donald Barlett and James B. Steele

All are data-heavy research, featuring some information that I found revelatory. Astounding, really. There's no way to really understand this era without the background provided by those diligent researchers and investigative reporters.