I use Stephen Skowronek’s Political Time model as a framework for thinking about politics. This model holds that periodic reconstructive presidents create a new “political order” providing standards that define what policy is politically possible or desirable, which I call a dispensation. Under the current Reagan dispensation, high tax rates on the wealthy are anathema and the stock market is the guiding principle of what is good economically. The Reagan dispensation is why neither party addresses problems like rising economic inequality, increasingly unaffordable housing, and rising voter anger over health care costs.

Effect of the Reagan dispensation on policy

Take a problem like the high cost of housing in the nation’s big cities. Proposed solutions are focused on supply; build more housing to bring down prices. This advice is based on home prices responding to supply and demand like ordinary goods. But housing is not just a good; it is also an investment asset. Investment asset price dynamics do not necessarily work the same as those for consumption goods. For example, rising price can increase demand and falling price reduce it. Similarly, increasing asset supply will not necessarily bring down prices. For example, new share creation through the exercise of employee stock options typically occurs during stock booms when prices are high (for obvious reasons). The increase in supply typically does not lead to price decline because of the positive effect of rising price on demand.

Housing still operates today as a normal (affordable) good in economically depressed areas, but not in most big cities. In the past most of the housing market functioned as a goods market does, but this has changed in recent decades. The prices of both stocks and real estate were range bound for a very long time before the mid-1990’s, after which they moved up and out of their historical range. The reason for the rise in stocks was a growing practice of corporate stock buybacks coupled with rising investor buying power fueled by foreign investment inflows due to rising trade deficits and rising income inequality. That is, stock prices rose relative to GDP because of rising demand for shares as assets.

With the rise of neoliberalism, real estate became more like financial assets through such things as mortgage bonds, real estate investment trusts (REITs), and other investment products that enabled investor money to be more easily deployed into real estate. Since traditional financial assets like stocks were getting more expensive in the late 1990’s, real estate provided value (I was getting a 15% yield in REITS then). The price of the REITs I followed soared in the early 2000’s as the stock market and interest rates fell and investors moved into this asset class. Investor interest in mortgage securities also increased; mortgage-backed securities held by commercial banks rose more than five-fold from 1999 to 2008. I note that increased mortgage formation over 1998-2005 did not lead to more affordable housing and a sustained higher level of homeownership, it merely enlarged the real estate bubble. This suggests that the real estate market was increasingly behaving more like an asset market rather than goods market. Increased asset demand from rising income inequality and foreign investment inflows stemming from trade deficits has bid up prices of all asset classes, including houses, making them increasingly unaffordable for ordinary people.

The Reagan dispensation is centered on tax cuts leading to deficit spending and on “supply-side” economics. Tax cuts shifted the environment to one that selected for shareholder primacy culture, which I see as the central feature of neoliberalism. Supply-side approaches to problems, such as the Clinton administration attempt to boost homeownership or Biden’s efforts at industrial policy, all involve government trying to bribe capitalists to do their job (grow productive capital). Investment in capital-intensive projects like more housing or new energy sources diverts funds away from more direct efforts at promoting shareholder value like share buybacks. Such things are discouraged under shareholder culture, making bribes necessary. Economic deregulation (such as legalization of stock market manipulation by companies) is the third key economic feature of the Reagan dispensation.

The supply-side policies Democrats have advanced for making the economy work better for ordinary people conform with the Reagan dispensation. Doing this is playing the politics of preemption. Preemptive-style policies have been complicated (e.g. Obamacare) or led to other problems (such as the recent inflation) and do not gain the desired support of the voters they try to help (if they did, their author would become a reconstructive president). Democrats supportive of continuing the politics of preemption are often called neoliberals by progressives. They respond (correctly, in my opinion) that Democrats need to win elections which they will not do if they pursue progressives’ objectives. The choice seems to be to follow the progressive ideas and lose quickly, or the neoliberal ideas and lose slowly. To do neither is not an option because of the Reagan dispensation.

Republicans make little effort to improve the situation for working Americans because their dispensation is all about removing obstacles for achieving maximum self-actualization for those at the top of the American class system, a goal they support whole-heartedly. They pay no political price for having this objective (when times are good) because they have always been upfront about being for society’s winners and indifferent to the rest. For example, President Trump has always been clear about his respect for “winners” and his contempt for “losers,” promising nothing to the losers who voted for him other than he will act to hurt those who oppose him on their behalf, which they are free to enjoy vicariously. Trump says these things, promises nothing, and wins handily. The political terrain is biased in favor of Republicans. This advantage is a benefit they gain from having the dispensation.

The FDR dispensation

When Democrat’s held the dispensation, policy standards revolved around high marginal tax rates and other policies that created an environment that selected for stakeholder culture and against shareholder primacy. The New Deal policy called for under the FDR dispensation (1932-79) is the opposite of the neoliberal policy called for under the Reagan dispensation that followed. The Reagan dispensation was explicitly anti-New Deal and sought to destroy it. The Right have always supported hierarchy and opposed efforts at “leveling” the social classes, which the New Deal policies under the FDR dispensation did (they cut top 1% income share in half).

As the party of the Right, Republicans vehemently opposed the New Deal, yet when Republicans finally regained controls of the government under President Eisenhower, they left the New Deal Order in place. They did not do this out of the goodness of their hearts; they felt politically constrained by the Roosevelt dispensation and the fact that their immediate Republican predecessor had been the disjunctive president Herbert Hoover. President Clinton was similarly politically constrained by the Reagan dispensation and the Carter legacy; he governed as a moderate Republican, deregulating finance and signing NAFTA and a capital gains tax cut into law.

The effect of the dispensation on electoral outcomes

My election analysis noted that Democratic presidential contenders running when another Democrat is in office have lost nine times in a row over the last 165 years, while Republicans in the same situation won about half the time. After further analysis I concluded that “candidates running when a member of their party is already president are unlikely to win when the other party holds the dispensation. Otherwise, they face probabilities consistent with chance.”

We can see the Reagan dispensation in operation in the 1988 and 2000 elections. In both the VP of a successful president ran for president. In November the favorability of the outgoing president stood at 57% in 1988 and 63% in 2000, both well above 50%. The Republican vice president won in 1988, while the Democrat lost in 2000. It was the other way around in 1960 when the FDR dispensation (1932-1979) was in force. Then it was the Republican VP who lost, despite 59% approval of the administration he represented.

The dispensation does not guarantee electoral success. Two Democrats ran while another Democrat was in office under the FDR dispensation and both lost because the sitting president of their party was very unpopular. Truman’s approval in 1952 was 27% and Johnson’s in 1968 was 42%. Similarly, John McCain lost badly in 2008 despite the Reagan dispensation because President George W, Bush’s approval was around thirty. Having the dispensation provides an electoral advantage—but not if you screw up.

How a new dispensation is created

The only dispensation change I lived through was the most recent one under Reagan. Near the end of the 1963-77 creedal passion period, I was a 17-year-old progressive liberal, having recently read Blaming the Victim and Rules for Radicals, who favored the very liberal Mo Udall in the 1976 Democratic primary. Two years later, I had moved to the right and was considering the Republican party. I was becoming increasingly distressed by the high inflation and my inability to achieve positive real returns on my college savings over the previous couple of years and had become a fiscal conservative. The 1980 presidential election was the first one I could vote in, and the only one in which I was involved in politics—as a College Republican. I supported Anderson in the primary but was adamantly opposed to nominee Reagan’s proposal to cut taxes leading to even larger deficits and could not vote for him. I disliked Carter because of his inability to control spending and bring inflation under control. I could not vote for either and voted third party for Anderson, though I had no involvement with that campaign, as it had been taken over by Kennedy people with whom I had little agreement. Reagan won and I resigned myself to massive deficit spending and a continuation of inflation.

The massive deficits did come, but lo, inflation went away. I was a child of inflation, having grown up in a world where everything simply got more expensive with time because of a thing called inflation. When I was very young, there were nickel candy bars, then, by the time I was 9 or 10, they were all a dime, then 15 cents and a quarter by the time I was in high school, at which point I was no longer interested in candy bar prices. Now it was gas. I paid 36 cents for gas when I mowed lawns at age fourteen, 50 cents when I was learning to drive, it was 65 cents at the marina where I pumped gas the summer before college, and finally $1.30 when I was a college senior. Throughout my life into my early twenties, I had never seen prices for anything go down. I had read about falling prices in books but had never seen it. Then, gas prices went down, to 70 cents in 1986 and CPI inflation fell to early sixties levels. It was astounding.

The job market sucked in the 1980’s, but it had sucked in the late 1970’s too, so there was no change there—but the change in inflation was palpable. I believe this was the thing that created the Reagan dispensation. I have previously written about what I think created the FDR dispensation: the reduction in hours worked per week with the same weekly pay enacted as part of FDR’s NRA program.

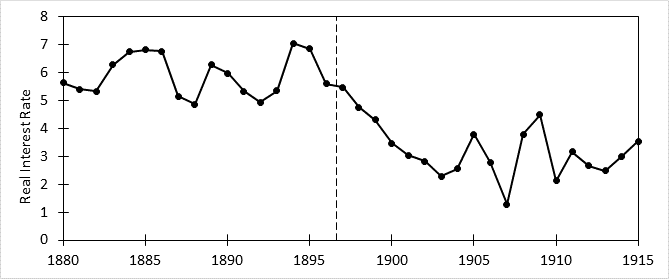

The McKinley-Roosevelt dispensation began in 1896 with a critical election, as do all dispensations. The 1896 election was critical because Republicans won the popular vote in four successive elections beginning in 1896, whereas they had lost the popular vote in four out of the five elections before 1896. How did this shift happen? A big issue since the Panic of 1873 had been deflation, which arose because of monetary policy based on the gold standard. Deflation made debts more expensive to service by increasing the real cost of interest. According to Thomas Piketty the long-run real return on capital is about 4-5 percent. Debt-financed enterprises like farming can go bankrupt if faced with sustained real interest rates well above this. As Figure 1 shows, before 1896, real interest rates were almost continuously above 5% because of the gold standard, which was bad for farmers.

Figure 1. Real interest rates over 1880-1915

This situation led to political factions forming around monetary policy. A largely Republican establishment faction supported the gold standard that enriched financial elites and was bankrupting farmers. Opposing them was a populist, Democrat-leaning faction who supported a more inflationary silver standard that benefitted farmers and not finance. A core element of the Lincoln dispensation (1860-95) was support for the gold standard, which was as strongly held as modern Republican opposition to higher taxes on the rich.

The power of the Lincoln dispensation meant only pro-gold “Bourbon” Democrats could get elected, meaning there was no real difference between the two parties’ economic offerings. In the depressions following the 1873 and 1893 panics deflation intensified, and farmers formed third parties calling for inflationary monetary policy such as the Greenbacks in 1874 and the Populists in the early 1890’s. Like all third parties in America, they were unsuccessful. In 1896 the Populists decided to join forces with the Democratic Party when they nominated 36-year-old William Jennings Bryan after his legendary speech ending with the rallying cry: you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.

This set the stage for a showdown over the gold standard in the 1896 critical election. McKinley won the election, but as Figure 1 shows, so did the populists. Real interest rates fell below 5% over the next couple of years and did not rise above that level for the next couple of decades. The war over the gold standard had ended; gold’s defenders had won the political battle, but the populists won the war—deflation went away. What happened was gold was discovered in the Klondike in August 1896 (vertical dashed line in Figure 1) and over the next three years the gold rush Jack London wrote about in The Call of the Wild ensued. The influx of gold increased the money supply, bringing moderate inflation and prosperity. The 1890’s Depression ended in June 1897, the economy boomed, and McKinley won handily in 1900.

McKinley was assassinated in 1901, and Theodore Roosevelt became president. A Progressive and larger-than-life personality, he re-introduced progressive themes into the Lincoln dispensation and built on the more active foreign policy begun under his predecessor. High tariffs and support for the gold standard, core elements of the Lincoln dispensation, were retained, making the political order McKinley and Roosevelt established more of a retooled Lincoln dispensation than true new dispensation, though it functioned electorally as a regular dispensation (and is treated here as such). In fact, it would be adherence to these core elements (Smoot-Hawley tariff and Hoover’s refusal to abandon the gold standard) that gave FDR the opportunity to launch a new Democratic dispensation.

So far, each new dispensation was created as a result of an economic change: for 1896, the onset of inflation, for 1932, strong wage growth, and for 1980 the end of high inflation. The issue in 1860 (slavery) was not economic and the replacement of the reigning Democratic Jackson dispensation (1828-59) was not accomplished through electoral politics, but through victory in the Civil War. The Lincoln dispensation was established by the fall of Atlanta in early September 1864 (which ensured Lincoln’s re-election), the unconditional Confederate surrender in April 1865, and ratification of slave emancipation in December.

The formation of the Jackson dispensation in 1828 was not like the later transitions in that there was only one formal political party over 1816-1828, Jefferson’s Republicans, which had split into four factions for the election of 1824, each with their own favorite: Jackson, Adams. Clay and Crawford. There was no electoral vote winner in 1824; the election was decided by Congress where Clay’s supporters voted for Adams in exchange for Clay being made next in line, which was enough to elect Adams. Jackson had won the most votes but was shut out of power. In 1828 he ran against Adams one-on-one and beat him handily. His supporters became the Democratic party. In 1832 Jackson won a landslide victory over Clay, still running as a member of the anti-Jackson faction of Jefferson’s Republicans.

Over the next few years those opposed to Jackson formed the Whig party. Three Whigs ran in 1836, the most successful of whom was William Harrrison. It was not until the 1840 election that a unified Whig party led by Harrison beat Democrat Martin Van Buren, re-establishing a two-party political system. Thus, the Jackson dispensation emerged out of the power vacuum created by the collapse of the Federalists in 1816, leaving a one-party state (President Monroe ran unopposed in 1820). It was more about the evolution of the modern political system than a reversal of a previous dispensation.

Though there were technically two more dispensations before Jackson, the Washington dispensation (1789-1799) and the Jeffersonian dispensation (1800-27) these did not function like the more recent ones do and have little relevance to the situation today.

Conclusions

As I recently concluded, Democrats will not win elections like the recent one until they regain the dispensation. What will not work is crafting better electoral messaging. Some Democrats point to how Republicans can lie repeatedly and fail to deliver on campaign promises, yet still win elections, arguing that better messaging is needed like what the Republicans have. This is wrong. Republicans can do this because they have the dispensation, meaning they win by default. Republicans’ “two birds in the bush” will always be preferred unless contravened by a “bird in hand” of bad outcomes under a sitting Republican president or good outcomes under a Democratic president seeking reelection. Hence, Democrats should work to establish a new dispensation.

Based on the small sample of dispensation shifts available to us it seems the most likely path for doing this is to change the economic reality experienced by voters in a favorable direction. This cannot be achieved by changes in economic trajectories only visible in economic statistics. This should be clear given the disconnect between the statistically good economic record the Biden administration achieved and public perceptions. It requires a tangible shift, like the end of inflation I marveled at in the 1980’s, the end of deflation after 1896, or the reduction in work hours for the same income produced by FDR’s NRA.

The easiest way to achieve a tangible positive effect is to counter a bad thing during an economic crisis, which history suggests might be in the offing. Before the New Deal there were periodic panics every 18 years on average. The 2008 crisis shows that under neoliberalism panics are a thing once again. If the former timing still holds, the next one should be “due” sometime around 2026. Some economists have raised the possibility of another crisis like 2008, or its inverse, stagflation.

For a deflationary crisis, the experience under the pandemic is instructive. The shutdown idled one-sixth of the workforce, an outcome that took two years of depression after the 1929 crash to achieve. And yet the economy bounced back in just two years thanks to large-scale fiscal stimulus.

This experience shows it is possible even today to produce dramatic effects on economic outcomes for millions of voters, if one starts from a depressed position. This suggests that the optimal time for Democrats to make a bid for a new dispensation is during an economic catastrophe that unfolded under a Republican administration. To do this, the Democratic president who comes to power after defeating the hapless Republican must practice the politics of reconstruction. That is, they must reject the Reagan dispensation and the Neoliberal policy that brought us to this pass, and implement their own vision for a better way, one that creates tangible, immediately experienced improvements in people lives, and they need to tell the people what they are doing and why, as the policy is having its positive effect on their lives. This last bit is needed to minimize losses in the next Congressional election.

To justify policy to produce such improvements requires a theoretical framework that explains why the old dispensation failed and why the new policy will lead to improvements. This Substack is about trying to construct such a framework.

I truly had hoped that, in his first address as president to Congress, and hence to the nation, that Biden was going to say very clearly, “I want to say to the American people, and particularly to the millions of working and middle class Americans whose lives and livelihoods have been undermined by 40 years of “Trickle -Down economics,” — what some people call “Neoloiberalism” — that we Democrats were wrong to go along with these Republican-initiated policies. I stand before you because we have seen the error of our ways. And I’m here to pledge to you that everything we do in this administration will be dedicated to making this right by you. We will be dedicated to returning to you the American Promise that when we work hard, when we do our jobs, we are valued and are rewarded fairly — and that the corporations and institutions that are essential to the well-being of our families and our communities are dong their part.” EYC.

And then, when the Dems tried to simply do more within the Regan Dispensation and workers weren’t “feeling it,” this might have spurred some sense of ‘agency’ among the working/middle class that would lead to new thinking and new approaches, or at least really good, public fights about these things, that might have brought to the fore in our public discourses the real reasons for the resentment and anger of the working and middle class. Perhaps this could have made the 2024 election about these things rather than about amorphous feelings about inflation and transgender issues . . .

It's very difficult to make politics go backwards, because the same process that lead to what you call a dispensation continues during the dispensation. That is, today's democrats are still fighting on the minority rights and progressive economics that lost to Reagan. When Biden came in and attempted to weakly revive those progressive policies, the result was a solid electoral loss. In order for democrats to create a new economic order, they need to identify new economic or political theory that can improve people's daily lives. Picketty etc cannot be the answer because they want to bring back the same policies that failed and brought in Reagan. My opinion is that the economic theory that will work is voluntarism, also known as rothbardian ancap. There are strong theoretical reasons to believe those policies would work, and they are also impossible for Republicans due to their social conservatism and corporate control. A democratic party that adopted voluntarism instead of progressivism would create a new dispensation.