The Capitalist Crisis

How financialization and inequality play into the crisis of our times

At the end of my inflation post I mentioned something called the capitalist crisis. Before I can explain what that is, I need to explain the concept of business resources (R). Back in the 1990’s I was looking for a way to get an idea of when the post-1982 bull market might come to an end, so as to avoid buying just before a market crash. To this end I came up with valuation measure I called P/R. This excerpt from a 2001 article explains it nicely:

P/R is the ratio of the price to business resources (R). R is calculated by adding the retained earnings (in constant dollars) for each year on a representative index (like the S&P500 index and its precursors) to R for the previous year. R is assumed equal to real index value for the initial year. For example, R in fall 1999 for the S&P500 was $950. Of this value, $880 represents accumulated retained earnings (all expressed in 1999 dollars) from 1871 to 1999. The other $70 represents the initial value of the index (in 1999 dollars) in 1871.

Put another way, R represents capital accumulation per share by the firms represented by the index. Assuming the stock index is sufficiently broad-based to be representative of the economy, R can serve as a proxy for capital accumulation in the economy. As capital and labor are both factors of production, GDP should be correlated with both. Since the emergence of an industrial economy after the Civil War, GDP per capita (GDPpc) has closely tracked R (see Figure 1). This correlation supports the idea that R can be used as a proxy for the amount of capital operating in the economy. The ratio of GDPpc to R represents the amount of per capita output generated per unit of capital and can be thought of as a measure of capital productivity.

Figure 1. GDP per capita closely tracks R over time

The capitalist crisis is defined as a drop in capital productivity (GDPpc/R). Capital productivity should remain at an approximately constant (high) value if capital is being used efficiently, which is indicative of a properly functioning capitalist economy. Indeed, from 1871 to 1907 GDPpc/R showed an average value of 45±3, and from 1941 to 2006 it showed an average value of 44±3 (see Figure 2). This demonstrates the presence of a healthy American capitalist system for 91 of the previous 151 years.

Figure 2. Relation between capital productivity (smoothed) and inequality

Following the Panic of 1907, GDPpc/R sharply declined to a new average level in the low 30’s, indicating the appearance of an unhealthy capitalist system (i.e., the capitalist crisis). The first capitalist crisis may be attributed to shortage of aggregate demand. The rich consume a smaller fraction of their income than do the poor. So, as inequality rises, and more income flows to the rich, aggregate demand falls and economic output with it. Hence the amount of output per person (GDPpc) declines relative to the amount of capital (proxied by R) available, implying a drop in capital productivity.

At low levels of inequality, there is no demand shortage; the limiting factor for GDPpc should be the amount of capital, and capital productivity should have a fairly constant high value. As inequality rises, a point should come when the income going to the working (and consuming) class becomes limiting, producing a demand shortage, and capital productivity declines. This appeared to happen around 1907. By the early 1940’s, inequality had fallen well below its 1907 level and capital productivity returned to its pre-crisis level, where it remained for more than six decades. The details of how this was achieved is explained in chapter 2 of America in Crisis.

When inequality again reached high levels early in the 21st century, capital productivity began to decline. This second capitalist crisis happened at a significantly lower inequality level, one that, based on the inequality level at the previous occurrence of the capitalist crisis, was too low to trigger a crisis through the aggregate demand mechanism. As described in chapter 4 of America in Crisis, the modern capitalist crisis has a different etiology. The decline in GDPpc/R that defines the capitalist crisis could also arise if not all retained profits were invested back in the company (that is, into productive or “real” capital). In this case, cumulative retained earnings (i.e. R) would no longer be a useful proxy for total real capital. Reduced real investment would be expected to slow GDPpc growth, while growth in R was unaffected, resulting in the observed reduction in GDPpc/R. This has indeed been the case. Three times more economic output (as a fraction of GDP) has been channeled into the stock market through dividends and stock buybacks since 2005 than during the previous quarter century as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Stock buybacks and retained profits less stock buybacks since 1980.

It would seem the current capitalist crisis is a consequence of financialization of the American economy. Some of this process resulted from specific changes made in economic policy and others from cultural changes resulting from these changes. To get a full account of what happened and how all this is connected, one would need to read chapters 2-4 of America in Crisis. In short, the use of high interest rates to combat inflation in the 1980’s created a situation in which the return from government bonds exceeded the return on capital from running a business (ROC). I track this situation with a measure I call the enterprise premium, which is the difference between ROC and financial return defined as the greater of real interest rate or real S&P 500 index appreciation over the previous 28 years (i.e. one stock cycle).

When the enterprise premium is positive, it makes sense for businessmen to plough their retained profits into their business, focusing on building great companies through organic growth. When everybody is doing this, the result is strong growth and a high demand for workers and suitable locations for business expansion. This tends to make businessmen see workers as assets and to desire good relations with the communities in which they wish to do business. These two groups are seen as stakeholders in the business. Furthermore, when executive compensation is restricted because of high tax rates on high incomes, there less of a connection between executive compensation and financial performance. Executives are not incented to prioritize financial results over operational objectives like new product development, customer satisfaction, market penetration, etc. The result of such an environment is evolution of a business/economic culture of “stakeholder capitalism” (SC) in which the objective of business is more than just financial results and their impact on share price.

When enterprise premium is negative, it makes sense for businessmen to put retained profits into financial investments (stock buybacks) rather than business expansion. Doing so is likely to be acceptable to the board of directors, who influence executive compensation. Furthermore, when high taxes no longer constrain executive compensation, stock options directly incent managers to prioritize shareholder value above all else. Finally, a financial focus creating high stock valuations can enable an SP businessman to more quickly build a great corporation by acquisition that his SC competitor can through organic growth. Hence a rising share of profits are expected to flow into financial rather than real capital as was shown in Figure 3. The result of this environment is the evolution of a business culture of “shareholder primacy” (SP).

Figure 4. Enterprise premium and relative wage of financial workers

Another consequence would be a tendency for financial workers to earn a higher wage than non-financial workers with similar amounts of training. Figure 4 shows how the relative wage of financial versus other workers has changed along with enterprise premium. From roughly 1940 to 1980, enterprise premium was positive, while financial workers relative wage and executive compensation were low. SC culture was rising in prevalence in the population of businessmen and economists during this time. Since the late 1970’s, SC has been in decline while SP culture has risen. In cultural evolutionary terms, the economic environment before 1980 (sometimes called the New Deal Order) “selected for” SC rather than SP culture. In contrast, the post-1980 Neoliberal Order of tax cuts and negative enterprise premium selected for SP culture.

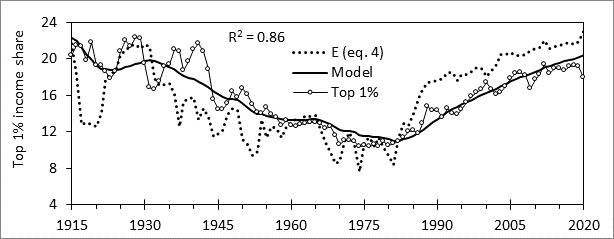

In the development given in chapter 3 of America in Crisis, I employed economic inequality as a proxy for the relative amount of SP present in business culture, with low inequality indicating mostly SC and high inequality indicating mostly SP. I used a standard cultural evolution model to do a pretty good job of explaining inequality trends in terms of cultural adaptation to a changing economic environment (E) defined as a linear function of top tax rate, strike frequency, and interest rates (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Cultural evolution model applied to the US 1913-2021

The rise in the prevalence of SP culture can explain the persistence of the Neoliberal Order despite the fact that has worked for a shrinking portion of the country as time has gone on. As SP culture affects the thinking of economists and economic policymakers as well as businesspersons, those who might object to the Neoliberal Order become marginalized.

Under SP culture stock buybacks grow in popularity (see Figure 3) leading to outsize stock market performance in recent decades (see Figure 6), helping to maintain a low enterprise premium, but also to create stock market bubbles. As proposed in my inflation article, increased dividends and stock buybacks (see Figure 3) reflecting these higher asset values appear to have largely eliminated the risk of inflation, which further bolsters support for continuation of the Neoliberal Order among policymakers.

Figure 6. Asset market performance 1875-2021

SP culture and the Neoliberal Order has drawbacks as well. High asset valuations are potentially risky because of the threat they create for financial crises according to economist Hyman Minski’s Financial Instability Hypothesis, as is described in chapter 4 of America in Crisis. One can see the forces involved in the recent crack up of crypto currencies. When a financial asset price (e.g. stock market) departs too greatly from the fundamentals on which its value supposedly rests (the underlying economy) it becomes prone to sudden declines in prices. When fundamental analysis (assessment of the value of the underlying business) shows that the share price is too high to warrant purchase, any decision to buy would have be based on technical analysis (assessment of recent price movements to assess the price trend). Simply put, if the trend is up, buying is in order, if it is down, one should sell.

Because it takes increasing amounts of money to buy as the price rises, investors must resort to using borrowed money to continue. At some point there is simply insufficient funds available with which to continue buying, and the rising trend must stop. At this point there is no longer any reason to hold the asset and selling occurs. Debts secured by assets falling in value can result in forced selling, to meet creditor demands, leading to a further decline in price. If the debt backed by the falling assets was itself used to back other debts, losses incurred by a decline in one asset market can spread to other markets, potentially leading to a situation where uncertainty and fear run rampant and financial arrangements that would work perfectly well in normal times collapse. This situation is known as a financial crisis, or Panic.

The recent crypto crash is an example of an asset price crash that was not linked to the larger financial economy, and so only resulted in losses for participants in that market. The 2008 financial crisis is an example of the opposite. It was ultimately based on a real estate, which is usually purchased mostly with debt because of the historic stability of real estate prices. This debt was considered sound because of the historical long-term stability of real estate, which made it suitable for useful as collateral for other loans, spreading the number of people involved should real estate go south. And when it did, the contagion spread.

That these complex “webs of finance” exist is because of the financialization of the economy and the prevalence of SP culture. To the SP-influenced mind, the webs are necessary and the solution to crises is better regulation. But regulation cannot work because highly intelligent operators lured by the prospect of riches will always find a way around them. The best way to eliminate the risk of financial crises is to reduce the amount of money seeking a financial, rather than real, return by promoting conditions that select for SC rather than SP culture.

But financial crisis is the least of the threats raised by the neoliberal order. After all we just had one in 2008 in which there was little loss of life. The more serious problem stems from what the capitalist crisis also represents, the secular cycle crisis. The details of this cycle will be covered in a future post (and are given in chapter 2 of America in Crisis). The take-home message is the same cultural forces leading to financial crisis through economic mechanisms, also lead to political crisis through sociopolitical mechanisms. Political crisis is typically worse than financial crisis: compare the previous American political crises of the Revolution (1% of population killed) and Civil War (2.4%) with the Great Depression, during which, surprisingly, the health of the population improved. As detailed in America in Crisis, the outcome of the Depression and WW II economic policy was the postwar era of excellent economic performance. Of course, WW II itself was a titanic disaster, but it was the outcome of political crisis generated by the German secular cycle crisis. Such an unpleasant outcome is available to the US for the current crisis, perhaps through political coup or election outcome as happened in Germany last cycle.

When I first started working on the analysis that would go into America in Crisis the idea of a political crisis generating another civil war in America seemed fanciful. Yet in recent years it is something polls indicate many Americans think could happen here. At that time the idea of an American coup also seemed fanciful (despite the 1933 Business Plot precedent), and then I watched something more serious than the Business Plot unfold on my television screen on January 6, 2021. The increasing presence of armed men at demonstrations, with enthusiastic support by large portions of a major political party provoke unsettling comparisons to events like Runnymeade as a harbinger of some sort of larger episode of internal strife.

Interesting analysis, Mike. I left Monsanto in 1986 for government employment as a biological research scientist because I saw that the company’s financialization had gained primacy over innovation. Inequality alarms me, and I see the deteriorating political climate as a result.