The hidden genesis of American malaise

It comes down to inflation

The secular cycle as a framework for understanding today

Peter Turchin proposed the concept of secular cycles in Historical Dynamics (2003) and applied this concept to four pre-industrial societies in Secular Cycles (2009). Secular cycles are centuries-long oscillations in population, economic inequality, elite numbers, sociopolitical instability and other social variables that operated in agrarian societies. They are divided into four periods, expansion, stagnation, crisis, and resolution.

Turchin extended his work to America in Ages of Discord (2016) and End Times (2023). Building on work by Jack Goldstone, he proposes a structural-demographic theory (SDT) to explain these cycles. In agrarian societies population growth drives rising inequality, which leads to elite overproduction, which leads to rising competition for elite positions in society and formation of elite factions that come into conflict leading to state breakdown or restructuring, often associated with the decline in population, inequality, at which point a new cycle can begin.

In post agrarian societies, there are no population cycles, but there have been inequality cycles, which serve the same role as population in SDT. I have presented the basic theory previously and will not repeat it here. Turchin uses proxies to empirically characterize inequality, elite overproduction and conflict components to test the proposed model dynamics. In my work on this topic, I have focused on how inequality cycles are created, relying on the simple relationships Turchin provides to characterize the political instability-generating effects of inequality.

In a 2019 paper, I used a cultural evolution model to explain trends in economic inequality over time as a measure for the relative prevalence of shareholder primacy (SP) versus stakeholder capitalism (SC) business cultures. Increasing prevalence of SP culture is characterized by rising inequality, which has led to the unsettling political situation today. SP calls for a focus on shareholder value and prioritizes financial performance above other metrics. It seeks to maximize the financial returns from commerce and to direct an increasing share of the proceeds from commerce to shareowners and away from workers or customers (other stakeholders). The financialization of the American economy under SP culture leads to an increased risk of financial crisis.

SC culture involves a focus on adroit business management with an objective to produce growth in enterprise size and status. SC corporate leaders consider shareholders, workers, customers and the communities in which they do business as allies in their quest for business greatness, fellow stakeholders in the success of the business. Workers fare better under SC culture, wages rise with per capita GDP, while they lose ground under SP culture. Rising SC culture implies declining inequality, such as happened in the fifty years after 1929.

Which business culture is selected for is politically determined

What kind of business culture is dominant (i.e., what culture economic conditions select for) ultimately depends on politically determined economic policies. American politics is determined by the interplay between two elite factions represented by the Republican and Democratic parties. In normal times, the degree of change achievable through politics is modest, the process of “strong and slow boring of hard boards” as Max Weber called it. The change obtainable this way often is insufficient to keep up with economic or cultural change.

American politics has developed a tradition of periodic “political revolutions” (called critical elections by political scientists) that can deal this problem. They lead to a major shift in policy preferences, what I call a political dispensation, for the winning political party. Business cultures are a product of evolution under the economic policies prescribed by the reigning political dispensation; SC culture arose under the Roosevelt dispensation, while SP culture grew out of the ongoing Reagan dispensation.

Shifts in inequality trends have all involved a critical election leading to a change in dispensation. These have happened at ever-widening intervals largely because of the aging of our political elite. Dispensations go bad with age, leading to discontent with both parties. This figure shows how the average rating by future historians of presidents declines from the reconstructive-type president who begins the dispensation, through the various articulative presidents from the same party to the disjunctive president at the end of the political cycle. The decline is statistically significant. It makes no sense that the late cycle presidents are intrinsically less able than the early cycle ones. Much more likely is that the political terrain is harder to navigate using an increasingly obsolete dispensation.

Inflation seems to be the fundamental driver of the American cycle

Inflation played the central role in the establishment of the McKinley and Reagan dispensations and an indirect role in the formation of the Roosevelt dispensation. I previously wrote about inflation. The general idea is inflation was historically linked to deficit spending during wartime, implying a relation between the two. A more formal analysis based on the quantity theory of money (QTM) identifies residence time (RT) of money as a key inflationary parameter:

1. ΔRT = Annual change in money supply / nominal GDP

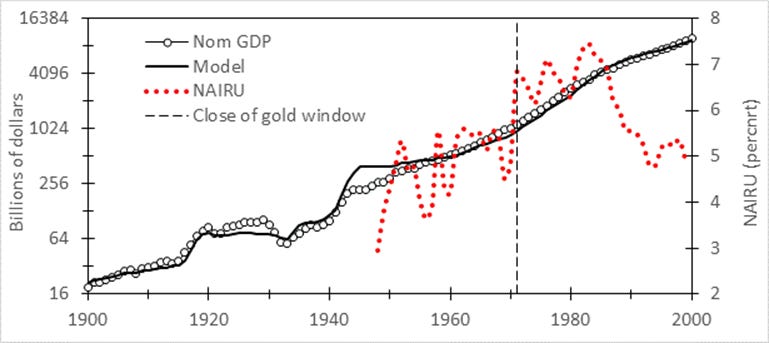

Money supply is defined as the sum of the national debt held by the public and the M3 measure of money. Values for these over 1960-2000 are available from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis database (FRED). I found a correlation between ΔRT and NAIRU, (the non-acceleration rate of unemployment) and used it to convert ΔRT values into NAIRU values. Figure 1 shows a plot of nominal GDP, a model for GDP (see equation 2) and values for NAIRU over 1960-2000.

2. GDP = 9.5 +0.91* money

Figure 1. Nominal GDP compared to Model (eq. 2) and NAIRU values

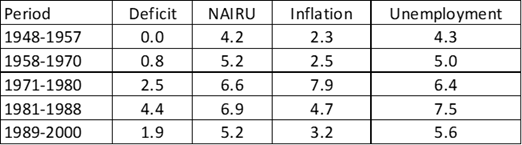

Figure 1 shows a rise in NAIRU over forty years and then a decline. Table 1 gives average NAIRU, deficits, inflation rate, and unemployment levels over sequential periods of roughly a decade in length. The first period featured low unemployment and inflation rates courtesy of a low NAIRU. The government managed a fiscal balance at this time and gold reserves held steady. I consider this era the high point of SC capitalism and the Roosevelt dispensation, even though the administration was Republican.

Table 1. Average values of economic statistics over time

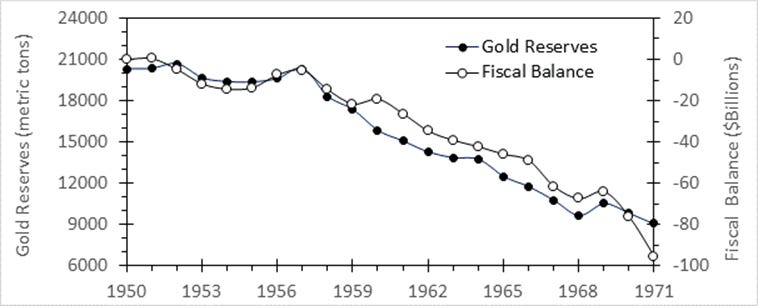

The next period saw NAIRU fully one percentage point higher than in the previous period, indicating a more inflationary economic bias because of chronic deficit spending. Unemployment rate was 0.7 point higher than before, less than the increase in NAIRU. As a result, unemployment was slightly lower than NAIRU, meaning inflationary conditions were present—yet inflation remained low. I suspect that consumption of dollars through exchange for gold acted as a buffer absorbing inflationary forces. Figure 2 shows a plot of US gold reserves. Note the steady decline during the 1958-1970 period. Inflation did finally start to rise in the late 1960’s leading to a temporary tax surcharge that produced the decade’s one budget surplus in 1969 (note the uptick in gold reserves in that year in Figure 2).

Figure 2. US gold reserves over 1949 to 1971

The end of the tax surcharge and return of deficit spending produced a sharply-rising NAIRU. The end of gold-dollar interconvertibility (see dashed line in Figure 1) meant no more inflation buffer. Under the Roosevelt dispensation, the objective of economic policy was maximization of economic growth leading to low unemployment and strong labor bargaining power, leading to rising wages. This is turn led to working class electoral support for Democrats which maintained the political dispensation. Up until the early 1970’s, this policy worked; the working class saw steady wage increases and the Roosevelt dispensation was politically secure.

Everything changed around 1971. A new era with a much higher NAIRU had appeared because of chronic (and larger) deficit spending (see Table 1). Fed interest rate hikes boosted average unemployment to recession levels in the 1970’s (see Table 1), yet NAIRU was higher still, so the result was a combination of high unemployment and high inflation, which was called stagflation. Higher unemployment meant wages failed to keep up with high inflation, which reduced enthusiasm for the Democratic party among the working class. Democrats suffered two landslide defeats in the 1972 and 1980 elections, the last of which ended their dispensation, paving the way for the implementation of economic policy selecting for SP business culture and rising inequality. It seems clear that 1971 saw the shift from a world in which the economic policy favored under the Roosevelt dispensation led to a well-functioning economy to one where it was failing.

As shown in Table 1, policymakers got a handle on inflation in the 1980’s. Though NAIRU was higher than in the seventies because of even larger deficits, unemployment was even higher, serving to drive down inflation as shown in Table 1. The end of the stagflation problem in the 1980’s established the Reagan dispensation. The end of a decade of inflation that made it difficult for middle class savers played a major role in Republican electoral success. Another factor was rising working-class votes for Republicans. It was job losses among the working class that generated the high unemployment responsible for the 1980’s inflation reduction. Working class anger at Democrats (Labor’s traditional supporters) translated into support for Republicans despite the fact that they had always been anti-Labor.

Efforts to reduce deficit spending in the 1990’s led to a lower average NAIRU, which allowed unemployment to come down while maintaining a low inflation rate. This period of relatively low unemployment and low inflation represents the high point of the Reagan dispensation, and like the Roosevelt dispensation’s high point, it happened under the opposition party administration. After the 1990’s the utility of NAIRU as I use it ended. Phillip’s curve plots used to directly measure NAIRU after 2000 no longer show any correlation between price acceleration and unemployment, so NAIRU cannot even be measured.

Since the start of the century, we have seen multiyear periods with low unemployment and inflation rates with high deficits. For example, 2016-19 saw average deficits at 3.8% of GDP with 4.2% unemployment and 1.9% inflation. That is, 1950’s-levels unemployment and inflation with 1980’s-level deficits. The modern inflation resistant economy comes at a cost—slower growth. Trend growth in real per capita GDP over 1948 through 1957 was 2.4% compared to 1.6% for 2010 through 2019.

What this means

We have an economic culture designed to provide excellent rewards to societal elites, those who are rich, smart, or credentialled, but relatively little for the rest. This culture generates an inflation-resistant economy tolerant of fiscally reckless behavior by political leaders. The policies that enabled the low-inflation modern economy have seen the fraction of income that goes to the top 10% rise at the expense of the rest. Peter Turchin calls this income transfer the wealth pump. Since 1980, some $70 trillion has been pumped out of the bottom 90% to the top tenth, most of which has gone into asset markets for stocks, bonds, real estate, or crypto, which has sent them to valuation levels that are extreme relative to historical values. One of the consequences of this are periodic financial crises, as we had before the Roosevelt dispensation.

Another consequence is a rising unaffordability for services produced by elites (such a college education or health care) or goods purchased by elites (such as housing). The wealth pump has kept elite income rising with economic growth—meaning the price of the services they provide have risen. And since they have more to spend on things like housing, they can bid up prices. This trend has made it harder for young working-class people to marry and start families. Which has had impacts on birth rates, labor force participation rates and attractiveness of simplistic solutions offered by populist figures that contribute to the rising political instability of the secular cycle crisis period.

Elites who benefit under the current economic order control both political parties. Neither wishes to see this order undone as happened under the Roosevelt dispensation. This creates a problem for “Blue” elites, a group I call mandarins who control the Democratic party, whose previous dispensation created the SC culture and an economy that worked for ordinary people. If “New Dealism” was no longer what being a Democrat was about, what would replace it? The solution adopted was to focus on cultural issues. Blue Democrats gained considerable political prestige through the Civil Rights laws. Furthermore, culturally conservative Southern Democrats left the party for the Republicans, moving its center in a culturally progressive direction. Building on their success and what seemed to be the tenor of the times, Democrats became a party of the cultural avant garde.

The capitalist elites who control the Republican party faced no such problem. They had always been champions of economic policy benefiting the rich. They capitalized on the failure of the Roosevelt dispensation to deal with 1970’s stagflation to gain power and form a new dispensation built around economic policy selecting for SP culture—what I call neoliberalism. They operate as champions of the cultural status quo versus Democratic progressives to gain votes from conservatives who do not benefit from their economic program.

Politics was now built entirely out of non-economic policy issues. Leaders of both sides implicitly accept neoliberalism, with Democrats less enthusiastic than Republicans—a residuum from their New Deal past. They compete on cultural issues, with Democrats adding social welfare goodies to the pot to offset the unpopularity that comes from being cultural vanguards. The result is a stalemate. Democrats alienate moderates with their cultural proposals and their incompetence on noneconomic policy issues when in power (e.g. how to properly withdraw from a miliary operation and how to control your borders) producing a thermostatic swing to the Republicans. Republican rule seems to lead to disasters (e.g., out-of-control deficits in 1992, Iraq War and financial crash in 2008; mismanaged pandemic in 2020) sending the pendulum back.

So what now?

The status quo is what has gotten us here. Democratic moderates call for a return to Clinton triangulation, while progressives seem to think nothing needs to change once Trump is gone. MAGA seems to want to eliminate competitive elections so as to remain in power regardless of their performance. After which they would co-opt or eliminate Blue elites, solving the elite overproduction problem and producing a bloodless resolution of the secular cycle crisis.