How cultural evolution works

And how it created capitalism

Cultural evolution occurs though different processes than biological evolution. In biological evolution, variation arises through gene mutation and environmental or behavioral influences on gene expression (epigenetics). Differential reproductive success provides the selection: the variants with the most progeny, on average, increase their frequency in the population relative to others. With cultural evolution, variation arises through innovation and mixing of competing cultural models. Selection still arises from replication, when a person acquires another’s behavior or knowledge through imitation or learning. The source of the cultural information or “meme” being transmitted (replicated) serves as a “cultural parent” to recipients or “cultural offspring.” The amount of time it takes cultural parents to enculturate their cultural offspring can be analogized to a generational time, except there is no necessary age relation between them. A cultural parent can be older, younger or the same age as their offspring. Cultural generations can be much shorter and cultural evolution much faster than its biological cousin. While it took many lifetimes for a valuable mutation like lactose tolerance to become widespread, a successful cultural practice like automobile culture spread throughout the American population in a single lifetime. Music and clothing styles spread even faster.

The subsequent development closely follows Robert Boyd and Peter Richardson’s 1985 cultural evolution primer, Culture and the Evolutionary Process. Unlike biological evolution, cultural evolution is Lamarckian; acquired characteristics are inherited. This greatly speeds adaptation to changed environments; rather than waiting for a beneficial mutation to slowly spread through the population, a superior practice can be immediately adopted by everyone. One type of cultural evolutionary mechanism is guided variation, in which individuals create knowledge that is valued by others who then copy them. That is, the direction of evolution may be guided by the evolving subjects rather than chance. This aspect of cultural evolution can give history a teleological aspect. For example, the history of the development of a technology will generally show a series of stages that yield better and better versions of the technology until an optimum is reached. This sort of phenomenon led early cultural evolution theorists to incorrectly imagine human societies evolving through stages of development, e.g., savagery, barbarism, civilization. But guided variation is only one mechanism for cultural evolution, the situation is far more complex.

Cultural transmission often makes use of instinctual heuristics that aid in the selection of cultural information worth learning. One of these is direct bias, in which cultural traits are assessed by would-be copiers based on their perceived quality before being copied. Direct bias is similar to guided variation, except the latter requires cognitive effort while the former often involves emotions, such as taking a liking to a song, an idea, the taste of a dish, or turn of phrase. A large investment of cognitive effort may not be required for the acquisition of these kind of memes.

Indirect bias refers to a situation where fitness (the propensity of a trait to being copied) depends on the presence of an unrelated trait. One example of indirect bias is frequency bias, illustrated by the saying “when in Rome, do as the Romans do.” Popular behaviors and beliefs are disproportionately likely to be imitated. Another is prestige bias, where successful or prestigious individuals are disproportionately copied. Prestige is often signaled by the presence of a symbolic prestige marker such as wealth, social status (e.g. a judge or pastor), possession of status goods, or personal behaviors (e.g. being “cool”). This bias forms the basis for such things as celebrity endorsements in advertising and the phenomenon of social influencers on the internet.

A combination of direct, prestige and frequency biases are likely responsible for many new cultural movements, such as changes in musical genres or fads. A new cultural movement might start with an innovator whose ideas “click” with influential individuals active in that cultural milieu (direct bias). Influential people possess symbolic markers signifying their credibility, to which people more tangentially involved in the milieu will respond via prestige bias. Once the next new trend has been identified, it expands the rest of the people in that cultural space via frequency bias.

Sometimes the bias trait is a symbolic marker of membership in a shared group or identity, which could be based on things like race, ethnicity, religion, age, gender, occupation, or popular culture preferences such as fandoms. The combination of biased transmission and frequency bias can result in the phenomenon of social contagion: the rapid transmission of a set of cultural attributes (infectious memes) resulting in an expanding group of like-minded individuals analogous to growth of infected people in an epidemic. This phenomenon is involved in the mechanism causing fifty-year cycles of cultural upheaval and political violence in America.

Cultural evolution readily gives rise to the phenomenon of group selection a situation in which a population evolves as if it were a single organism, whereas it is much harder for genetic evolution to proceed in this fashion. The reasons for this are biased transmission and the speed at which memes spread compared to genes. For example, a cultural variant that increases an individual hunter-gather’s success will result in acquisition of a prestige marker, speeding its spread through the tribe through prestige bias. At the same time in-group vs. out-group bias will inhibit the spread to other groups. Frequency bias encourages migrants into the group to adopt this meme while those moving to other groups will likely abandon it to better fit in, Thus, new memes appearing in a one group will tend to stay within that group long enough for them to be adopted by the entire group. Consequentially, the cultural inventory of the entire group evolves like the genome for a single organism. Entire populations (cultures) evolve in competition with other cultural groups. Hence it is common to see genetically similar peoples with different languages and cultures living in close proximity, e.g., 229 tribal nations in Alaska alone.

Such group evolution can occur in subsets of a larger population. For example, in my post on economic evolution, I treat businesspersons as a group evolving in this way in response to changes in the economic environment caused by government economic policy. In this example it as a very genetically and (non-economic) culturally heterogeneous collection of people who share a common commercial culture that changes via guided and prestige-biased selection in order to adapt to a changing economic environment. My previous post treated African American student culture evolving in response to a changing economic and social environment caused by government policy.

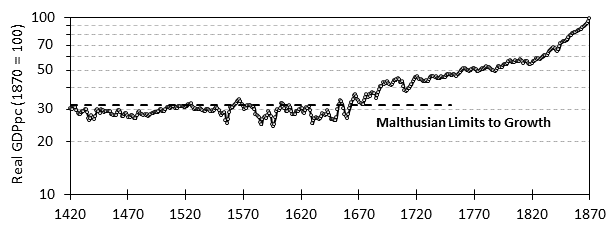

Prestige plays a major role in the cultural evolution that drives the historical processes of interest to me. Capitalism, for example, is a cultural construct like race or gender, that created a new route to the acquisition of prestige: the accumulation of capital. If we define capital in the Marxian sense as “the means of production” then accumulation of capital by individuals, means a greater productive capacity can be generated by the same number of people. This would translate into a rising per capita GDP (GDPpc). Figure 1 shows a plot of real GDPpc for England over 1420-1870. For the first two and a half centuries GDPpc was flat, and then, in the last third of the 17th century to began to rise and never looked back.

Figure 1. Real GDP per capita in England 1420-1870

Sometime before 1670, a “capitalism meme” appeared in the English population and started to spread throughout the population. The hypothesis I advanced in Section 7.2 of America in Crisis was late Medieval and Rennaisance European leaders had begun to appreciate the link between the amount of (taxable) trade in their domains and the size of armies they could raise and the prestige they could gain with them. By the late 16th century, patents were being issued to encourage the development of new trades and prestige awarded to entrepreneurs like Sir Walter Raleigh who promised to bring new revenues to the crown. The growth of business necessarily requires a growth in that which makes it possible (capital) and so the kind of behavior the government was trying to encourage by handing out prestige was capital accumulation. The result was the appearance of route to prestige achievable through being a capital accumulator, that is, a capitalist. As people pursued this route, they gained prestige making their example more likely to be followed and speeding the spread of capitalism though the commercial class and trades, until it was prevalent enough to start generating discernable economic growth.

Once a growth ethic was established there was now a demand for the creation of more kinds of capital for capitalists to accumulate. Creating new useful things is the domain of technology, a cultural category that pre-dates Homo sapiens. Around the same time as capitalism was evolving in Britain, a “force multiplier” for technology development was also evolving, modern science, which can be thought of as a merger of natural philosophy with technology. Its appearance is known as the Scientific Revolution. An example of how science bled into technology and capitalist development is the vacuum pump, invented around 1650 as a scientific tool. More commercially-minded people saw that the vacuum could be used to do work (like pumping water) and engaged in experimentation leading to the development of the steam pump in 1698 and the atmospheric steam engine in 1712. James Watt’s improved steam engine is often considered to be a core element of the Industrial Revolution beginning in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Throughout the development of capitalism, the scientific and industrial revolutions, and the rise of the first wave of industrialized nations, capital remained as the means of production. Closely connected to capitalism is finance. A firm might offer partial ownership (shares) of the company and sell them to investors in order to raise funds to purchase the capital need to start or expand the business. These shares could then be traded on a share market, which would establish a price for a fixed piece of the company, and hence a value for the company as a whole. The value of a company is also its capital, because this is what, when combined with labor, creates the revenue and profits that make a company worthwhile. This means there are two ways of looking at capital: means of production or share price. Capitalists who seek to grow the first are SC capitalists, while those who seek grow the second are SP capitalists. In some cases the actions taken by both kinds of capitalists would be the same, but in other cases, such as use of share buybacks or sacrifice of profit margin to build market share, they can differ. It is these differences that produce the differential economic outcomes for the two cultures.

In time, financiers realized the “growth ethic” that led capitalists to grow capital meant they also grew share prices as a result. That is, stocks go up in the long run and capital gains can be an important component of financial return from stock investing. This understanding was not achieved until the 1920’s bull market, which was followed by the Great Depression and the New Deal Order, which created conditions selecting for SC culture under which capitalists continued to treat capital as means of production rather than share price. With the collapse of the New Deal Order, the objective of capitalism gradually shifted from maximization of economic growth to maximization of share price growth as SP culture took hold. And this is how we came to be where we are now, with high levels of economic inequality with the associated political and financial instability.

To the extent that American civilization is a capitalist civilization, the measure of our civilizational greatness is no longer the prosperity or well-being of its citizens, or its ability to do great things like defeat Hitler, land on the moon, or deal with the threat of climate change. Rather, it is its ability to build monumental financial architecture, which unlike the monuments left by former civilizations, have only an abstract and ephemeral existence.

This has relevance today, because if the US is truly moving into a new Cold War and we wish to avoid it becoming a hot one, America will need to wage this competition on cultural grounds, in which the quality of one’s civilization matters.

Interesting article.

You might be interested in reading my book, From Poverty to Progress: Understanding Humanity’s Greatest Achievement. It includes a chapter on Cultural Evolution and its relationship with modern human material progress.

https://frompovertytoprogress.com/from-poverty-to-progress-book-page/

Do you think institutionalised business and government necessarily leads to decay in subsequent generations? Both mission-orientated government and first generation entrepreneurs can deploy resources in incredibly productive way, with dynamism, flair and innovation. Meanwhile financialised economics and social spending geared bureaucracies seems to be more of a placeholder economics- celebrating at the tiniest incremental result, in the shadow of rusted Goliaths.