There has been a growing feeling that something is wrong with the direction America is heading since the turn of the century. The idea that we live in a time of crisis has gained currency in recent times. America in Crisis is an analysis of the political and economic dynamics responsible for this feeling. I use a cyclical concept, not William Strauss and Neil Howe’s generational cycle referred to in the previous link, but Peter Turchin’s secular cycle, with corrections that address some of the issues raised in the cited review. I believe a major driver of society is cultural evolution and talk about it a lot. There is also quite of bit of political, economic and financial discussion as I believe these disciplines are also very important to understanding what is going on. I wrote up my analysis in a book with the same name as this substack. I cover some of the material in the book here, plus new insights as they occur to me. For easier comprehension it may help to read posts in sequential order so that when an older post is referenced there is some familiarity.

The idea that America history unfolds in cycles is not a new idea. Here I introduce an American cycle scheme based on the idea of secular cycles proposed by Peter Turchin and the demographic-structural theory that explains them. Secular cycles are long-duration (centuries) oscillations in population, economic inequality, elite numbers, sociopolitical instability and other social variables in agrarian societies. They consist of four phases: expansion, stagflation, crisis, and depression.

Each period has characteristic features. The expansion period sees a rising population, a strengthening state, minimal factional strife, and lower economic inequality. The stagnation period sees slowing population growth and rising economic inequality as population approaches its cycle maximum. State strength reaches its maximum and begins to decline while increased elite numbers result in increased competition (a process Turchin calls elite proliferation).

As the population peaks and inequality is reaching cycle-maximal values the crisis period begins. State power declines, elite competition leads to rising polarization and, sometimes, conflict. The final depression period often involves some sort of economic collapse, major internal conflict, or large-scale war. It sees population reaching a minimum and, frequently, low or declining inequality. The state attempts to reassert its authority, which is complicated by the continued presence of strife amongst elite factions. Elite strife is resolved during the depression phase (which is why I prefer to call the fourth phase resolution rather than Turchin’s depression). Resolution is typically accompanied by a reduction in elite numbers due to economic shifts or military/political defeat.

Population growth is the cycle driver. In an agrarian society, the economy is largely based on agriculture. GDP is ultimately limited by the fixed amount of arable land. All available land will come under cultivation as population grows until the land is filled up and economic output peaks. Further population rise leads to labor surplus and reduced output per person, while population-driven demand for goods outstrips fixed supply, causing prices to rise. Thus, periods of rising population tend to be associated with lengthy periods of price inflation known as price revolutions. Rising prices for the output from land combined with a fixed supply means rising land values, increasing the wealth of the landowning elite. Meanwhile, labor surplus leads to falling real wages, impoverishing workers. This means times of rising population in agrarian societies translate to times of rising economic inequality.

Rising inequality means a larger share of the economic pie goes to elites, who flourish and see their relative numbers grow (elite proliferation). With rising numbers, competition between elites rises, particularly after the population peak and the start of the crisis phase, when the economic situation becomes more challenging for them. Over time, elite competition shades into rising polarization and then to political conflict, Resolution typically involves internal war, economic depression or state collapse. This tendency is tracked by the Political Stress Indicator (PSI) invented by political scientist Jack Goldstone which Turchin adapted for use with secular cycles. The eventual outcome is a reduction in elite numbers, through both/either combat mortality and loss of elite status for the losers of the conflict that reduces PSI to “safe” levels. Elite numbers and PSI rise and fall with inequality. More details on this I give in chapter 2 of America in Crisis and here.

Turchin has applied the secular cycle concept to a modern industrialized nation, the United States and found two cycles, 1780-1930 and a still ongoing cycle since 1930. In lieu of population, he uses a composite of measures of well-being (wage/GDP per capita, male stature, life expectancy, and age at first marriage) plus percent foreign born to track the cycle. Turchin proposes that the basic demographic mechanism for agrarian nations still holds after industrialization. The role of arable land in an agricultural economy is replaced with a labor demand function: GDP divided by labor productivity. Labor force growth faster or slower than demand translates to rising or falling inequality. Turchin’s use of percent foreign born as one of his measures of the secular cycle reflects this model. Turchin sees the resolution of the first secular cycle involving the reduction in immigration after 1924.

This mechanism is not compatible with economic theory which holds that growth in GDP is largely determined by investment. Firms increase investment and hire workers when business is good (consumer demand is strong). Since workers are also consumers, demand (and consequently, investment) should grow with employment. There should be no limitation on GDP expansion. The driver of the post-industrial cycle is then not demographic. A better choice for cycle driver is economic inequality, which is the principal factor responsible for elite proliferation, PSI and the political/economic crisis, resolution of which ends both agrarian and modern secular cycles.

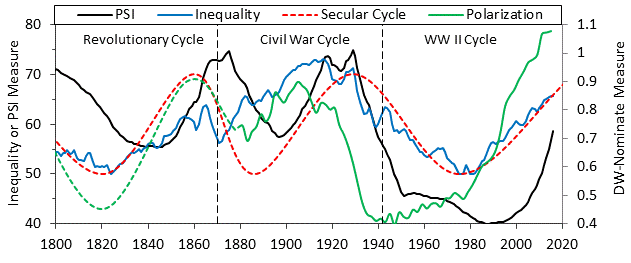

Figure 1. American secular cycles as defined by inequality, PSI and Polarization

Figure 1 shows a plot a measure of economic inequality I developed. Also shown is PSI and the DW-Nominate measure of political polarization (which tracks elite competition). I employ an easier-to-use version of Turchin’s PSI in this figure. DW-Nominate measurements are not available before 1879, but one would expect polarization to been high just before the Civil War and low in the period called the Era of Good Feelings that followed the 1816 collapse of the Federalists leaving a one-party state. A hypothetical extension of polarization before 1879 was made (see dashed green line in Figure 1) by assuming a 1857-65 polarization peak (Dred Scot decision to Civil War end), a trough in 1820, when president Monroe ran unopposed, and a peak over 1775-1783 for the Revolutionary War.

The inequality plot shown in Figure 1 is consistent with the two secular cycles Turchin found, whereas the PSI and polarization trends are consistent with three cycles and with the conception of American political history as three republics. These secular cycles are denoted in Figure 1. In this scheme, the first American cycle is a standard agrarian cycle, whose crisis arose from a demographic mechanism described by Turchin in his book Ages of Discord. For Turchin the Civil War begins a crisis period, one of the “ages of discord,” referenced in the title that lasts until its resolution during the 1920’s.

I found his account for a 1920’s resolution unconvincing in that it has the Depression and WW II, traditionally seen as a major turning point American history, not as a crisis at all, but rather as part the first phase of the next cycle. For me, the Civil War and the Depression were separate crises, the resolutions of separate secular cycles. One reason this is hard to see in the well-being measures Turchin used to identify the American secular cycles is the brevity of the inequality dip after the Civil War. The inequality decline reflects the emancipation of millions of former slaves and the associated destruction of plantation elite wealth. The eclipse of the landing-owning elite provides the decline in elite number and PSI characteristic of the end of a secular cycle (see Figure 1). That the inequality decline was so brief is explained by the rapid rise of a new industrial elite, rather than the recovery of the landowning elite. In fact, landholders ceased to be political relevant on the national level after the Civil War, signifying the end of agrarian cycles. The old mechanism was no longer operative, a new mechanism involving economic culture (as proxied by inequality) was now responsible for the cycle.

The Civil War was a typical end for an agrarian cycle, similar to the resolution of the colonial cycle by the American Revolution. The resolution of the English Tudor-Stuart cycle before that had involved both civil war (1642-51) and revolution (1688), and the Plantagenet cycle before it was resolved by the Wars of the Roses, yet another civil war. It was the end of the post-Civil War cycle (see Figure 1), which involved no internal war or state breakdown, that needed an explanation, which I proposed in a 2017 paper and in an expanded form in chapter 2 of America in Crisis.

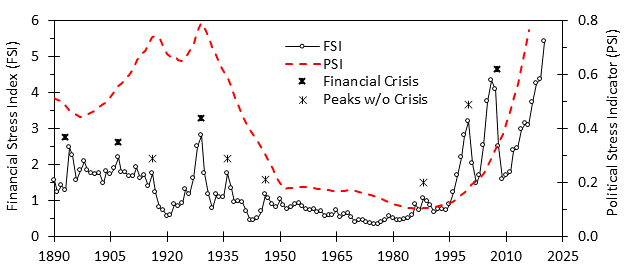

The explanation I gave introduced the capitalist crisis, which I previously wrote about from the perspective of the current crisis. I re-interpret the capitalist crisis as a financial crisis in chapter 4 of America in Crisis (and also here) by combining financialization associated with rising shareholder primacy (SP) culture since 1980 with Hyman Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis to argue that growing inequality as the secular cycle progresses produces a rising risk of financial crisis/collapse in parallel with that of political crisis/collapse caused by rising elite numbers. I proposed a financial stress indicator (FSI) analogous to PSI to track this, a plot of which is shown in Figure 2. I note that only some FSI peaks manifest as financial crises, and even those do not produce a secular cycle resolution unless they are associated with a high PSI, which I hypothesize creates an incentive act to address its causes. I noted that last cycle, it took three successive financial crises before ruling elites were willing to take action--the fact that polarization had already started to decline a decade earlier (see Figure 1) probably helped.

Figure 2. PSI and FSI over time

The resolution of the last secular cycle centered on the governmental response to the financial crisis outcome rather than the more conventional political crisis. The post-1929 bear market was financially traumatic to the capitalist elites. In a 1932 Forbes article, private equity specialist Benjamin Graham noted that a third of the industrial companies on the New York Stock Exchange were trading for less than their liquidation value. In other words, one third of America’s top corporations were worth more dead than alive―a state of affairs that called into question the justification for capitalism in the eyes of many. Economic policymakers were puzzled by what the economy was doing and the Republican administration then in power was unable to cope with the developing catastrophe. As a result, the Republican dispensation established by Lincoln and renewed under McKinley and T. Roosevelt was swept away in the election of 1932. The new Reconstructive president Franklin Roosevelt would guide the country through the resolution phase (1929-42) of the second US secular cycle and set the stage for the economic boom that defined the expansion phase (1942-1973) of the third cycle.

This resolution phase had followed a crisis phase beginning with the appearance of the capitalist crisis in 1907. The key problem of this crisis was a shortage of demand relative to the productive forces now present in the burgeoning industrial economy. Elite responses included such things as the rise of marketing to direct sales to one’s own company, introduction of consumer finance to support increased demand by potential customers lacking the ready cash for purchase, and increasing profit margins through union-busting and other measures to extract more profit from existing sales. A novel response is illustrated by Ford’s effort to introduce productivity-enhancing, but mind-numbing automation to his automobile manufacturing process in order to slash prices and so induce sales, while maintaining margins. Ford encountered huge worker turnover problems due to the onerous working conditions the new tech created. Ford came up with a counter-intuitive idea: reduce labor cost by doubling workers’ pay. The idea was that the savings in turnover costs would more than make up for the increased labor cost. His ploy was successful, about which he opined in his 1926 book “the owner, the employees, and the buying public are all one and the same, and unless an industry can so manage itself as to keep wages high and prices low it destroys itself, for otherwise it limits the number of its customers. One’s own employees ought to be one’s own best customers.”

Social scientist Kitty Calavita has described the role of the state in a capitalist nation as the “manager of the collective interests of the bourgeoisie.” From the state’s perspective, the advertising and consumer finance responses amounted to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. These approaches could solve the problem for some, but the core problem was capitalists collectively needed a bigger market to exploit. Squeezing worker incomes made the problem worse by depressing consumer demand, even though it could benefit the individual companies pursuing it. On the other hand, Ford’s “proto-stimulus” created new demand outright, growing the collective pie (and making out handsomely to boot). It would be the conceptualization advanced by Ford that would be adopted by others. This cooperative attitudinal variant was more appealing in terms of Christian morality and appeared to work better than individualistic approaches, and so grew in mindshare among elites. Declining polarization after 1920 (see Figure 1) might be a manifestation of rising elite cooperation. I give other examples in chapter 2 of America in Crisis.

The formal theory that undergird the solution to the post-1907 capitalist crisis was developed by J.M. Keynes, who proposed aggregate demand does not necessarily equal the productive capacity of the economy and sometimes falls short. A straightforward solution might be increased government spending (fiscal stimulus), which happens any time there is a major war. This was too radical for the Roosevelt administration in its response to the Great Depression. Instead, the primary tool used in the 1930’s was monetary stimulus, in particular a dollar devaluation resulting from the termination of the gold standard in 1933, which was largely responsible for the subsequent economic recovery. This policy and fiscal deficits resulted in the injection of $32 billion over 1933-37 (equivalent to $8 trillion in 2021) into the economy. An analogous policy response was made after the 2008 financial crisis, when $6.3 trillion (post crisis less pre-crisis deficit + Fed QE actions over 2008-2012), the equivalent of $8.6 trillion in 2021, was injected into the economy.

These policies had similar effects. The 1930’s stimulus was terminated after four years due to fears of inflationary risks from sustained deficit spending, but over the four years it was in force, unemployment rate fell 42%. The effect for the next cycle was about the same, a 39% decline in unemployment over four years. Policymakers had learned and for this cycle stimulus was not stopped after four years After three more years unemployment reached the previous cycle low and three years after that it reached 3.5%, a value not seen in half a century, the recovery was then interrupted by the pandemic, but has since resumed, reaching 3.4% in January 2023.

Unlike after 1929, the 2008 monetary intervention was made before the financial system collapsed. The purpose of the modern intervention was the protection of investors from ill effects of the crisis, preventing financial collapse. This is shown by the subsequent trajectory of the stock market. Both the 1933 and 2008 efforts to fight deflationary forces created price inflation in equity markets. Between 1932 and 1937, equity prices rose 325% before going into a prolonged bear market. Similarly, from 2009 to just before the sharp 2020 correction, stocks rose 333%. After this initial rise, the similarity between the two eras ends. Stock prices did not advance sustainably above the 1937 peak for 13 years, Recovery from the 2020 pullback took less than a year after which stock prices continued to advance to reach a level three times the pre-crisis peak in less than 15 years, a feat that took forty years to achieve after 1929.

More importantly, the response this cycle did not include the high marginal tax rates that select for stakeholder capitalism (SC culture). Hence, the impact of post-2008 policy on the real economy was smaller: unskilled wages fell by 3% over 2008-12 compared to a 28% rise over 1933-37 (40% from 1929). The absence of tax policy selecting for SC culture meant the difference between beginning the secular cycle resolution period in the last cycle (leading to continued democracy and postwar prosperity) and continuing the crisis period for this cycle (leading to an unknown future).

The resolution of the capitalist crisis last cycle was achieved by fiscal stimulus (under SC-culture producing conditions) from spending for WWII. High capital productivity persisted for more than sixty years after the war showing that a long-term solution to the capital productivity problem was achieved by actions taken during the war and not before. It is unlikely that fiscal stimulus alone was responsible for the long-term restoration of capital productivity. After all, WWI had provided fiscal stimulus but had not solved the problem. Between 1916 and 1920, nominal GDP grew at a rate of a 16% per year, however this strong growth was associated with a 17% consumer price inflation rate. To deal with the excessive inflation associated with WWI, the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates by three percentage points from December 1919 to June 1920, inducing a severe deflationary depression. Real unskilled wages rose 11% over the 1916-20 period, but lost most of this gain from 1920 to 1921. Afterward, wage gains were small; real unskilled wages rose only 8% over 1920-29.

In contrast, nominal GDP grew 13% annually with 7% inflation from 1940 to 1948. The Federal Reserve took little action to suppress inflation after the war. Despite this, inflation averaged only 2.5% between 1948 and 1973. Strong growth leading to broadly shared wage gains occurred during and after WWII. In contrast, economic growth was more tepid during and after WWI, and wage gains were not broadly shared. A comparison of economic statistics for the 1916-29 and 1940-73 periods illustrates this. The first period saw per-capita GDP growth of 1.8% and real wage growth of 1.4% and 2.3%, for unskilled and production workers, respectively. The corresponding figures for the second period were 3.0%, 2.4% and 2.6%

These excellent results reflect SC culture-creating policy during the war. An example of this were wage and price controls implemented by the National War Labor Board (NWLB) and the Office of Price Administration. The New Dealers designed wage policy so that increasing the wages of low-income workers was easier than increasing wages of high-income workers, which when combined with the upper income-suppressing effects of high marginal tax rates produced a flatter income structure and falling inequality. More details on this can be found in chapter 2 of America in Crisis and here.

Unlike last cycle, the second round of interventions have done nothing to resolve the capitalist crisis. They began with President Trump’s tax cut in December 2017 and were augmented with additional Fed QE operations and a series of COVID-19 relief bills. Altogether, they produced $9.8 trillion worth of monetary stimulus over 2018-21. A substantial fraction of this stimulus has been fiscal, including direct payments to millions of Americans. Another portion of this $9.8 trillion has been in the form of tax cuts and Federal Reserve QE operations, which add money to the financial system, where most of it tends to stay. Current policy on taxation ensures continued high inequality and PSI just as current financial policy ensures high FSI. As a result, the country remains vulnerable to both financial and political collapse.

A key difference between the two cycle crisis era lies in control of the remedial policy. Resolution of the previous crisis was accomplished through economic policy administered by the Roosevelt Administration. This was possible because Roosevelt’s party had won landslide victories in the 1930 and 1932 elections making him a Reconstructive president. In contrast, the solution to the 2008 crisis was administered by central bankers, who operate on behalf of financial elites and not the public. That it happened this way is because the Reagan dispensation had not yet fully degraded, leaving President Obama as a Preemptive president like Grover Cleveland, unable to exploit an economic crisis for his party’s benefit as FDR and Reagan were able to do. Hence, recovery policy would be favorable to financial interests and not the public.

This fact and subsequent efforts on behalf of investors in 2018, 2020, and most recently in the bailout of SVB depositors shows that the financial collapse that led to the resolution of the last secular cycle crisis without an internal war is not an option for this crisis. This leaves the more “old school” political options. Figure 1 shows about 20-40 years elapsed between extremes in polarization and in PSI. Polarization is a measure of the intensity of elite (in this case political) competition which, as the secular cycle progresses, translates into rising PSI. Left unchecked, rising PSI may lead to serious civil unrest, state collapse, or internal war. Figure 1 shows high levels of polarization were already present in the mid 1990’s, suggesting we could see some sort of major political conflict during this decade or the next.

Although the conflict often involved internal war, the conflict can be external. The Roman secular cycle crises of the 3rd and 5th centuries involved external invasions to perhaps a greater degree than civil wars, and the Anglo Saxon secular cycle was explicitly resolved by William of Normandy’s invasion in 1066. More recently, Germany’s last secular cycle ended with the military defeat of the Nazi regime in May 1945, while Japan’s ended with nuclear detonations on two of their cities. So, this too may be an option. A plausible scenario along these lines might be a war with China over Taiwan that requires tax increases on high income earners in order to prosecute without runaway inflation.

An intriguing option would be a political collapse of one or both of the political parties, leading to a reorganization and emergence of a politically potent new party that elects a Reconstructive president and implements a solution to the capitalist crisis. In 2016, presidential candidate Bernie Sanders talked about the need for a political revolution in America. Electing a Reconstructive president in a critical election that then goes on to resolve the secular cycle crisis by implementing something like SC culture was what he was talking about, though he would not use these terms of course.

What is "SC culture"? And what does SP stand for?

Marx was the one that coined the phrase 'managing the interests of the whole bourgeoisie.' This is all very interesting.