Trying to learn from history

How an appreciation for historical cycles provided insight into how history unfolds

Dan Gardner writes about how the absence of hindsight magnifies the perceptions of problems in society:

It’s easy to make the present look more frightening than the past. People do it all the time. As I’ve shown many times before in PastPresentFuture posts, if we examine the news archives from even the most golden years of the past you care to name, we find there were terrible things happening and worse threatening — and people were afraid. That’s not how we remember those “golden years,” however, thanks largely to hindsight bias. So, when we casually compare the frighteningly uncertain present with our perceptions of the past, we imagine the present is so much worse than ever before.

Charles Shaughnessy responds with the idea that the present is a time of special significance:

I believe we are at exactly such an “ event horizon.” AI, climate change, nuclear proliferation, a crisis in the perception and manipulation of reality, a deepening distrust in the institutions that define our societies….these developments are forcing us to abandon deeply held assumptions and faiths and we see the world we know as “ coming apart.”

To which Dan responds

Such inflection points exist in history but people have a terrible track record of spotting them as they’re happening. Again, go to the archives. People are forever saying things like “this is a revolutionary moment.” Maybe. Some moments are. But a little more humility in the accuracy of our perceptions and judgments is called for.

I agree with Dan in that it is very difficult to interpret the significance of the times in which we live, making it hard to claim that the present is a time of special danger. But I also agree with Charles; I believe we are living in a time of crisis that I (and others) anticipated 25 years ago. After all, I wrote a book and have a Substack called America in Crisis.

So how do I square these two? I start with the aphorism of historian George Santayana: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” which implies there are “lessons” to be learned from history. But which lessons apply? History has many lessons that are often contradictory, how do you know which ones to apply?

One way is to find periods of history that seem similar today, as David Roman does here. Roman contests the validity of a “lesson from history” offered by the 1938 Munich Agreement. This lesson is typically invoked to support taking a hard line against expansion of regimes the invoker does not like. Cold Warriors invoked it to support military intervention on behalf of South Korea and South Vietnam against Communist forces in the decades after WW II. Today, opponents of Russian dictator Vladimir Putin invoke it to support aid to Ukraine after the 2022 Russian invasion. Roman argues that what Chamberlain did at Munich was the right choice and uses this conclusion to support a policy of appeasement toward Putin today.

Hindsight tells us that while the Korean intervention was the right thing to do, the Vietnam intervention was not, while the jury is still out on Ukraine. Roman’s post shows the same event can provide contradictory lessons, implying that nothing can be learned. Is Santayana wrong then? Perhaps, but then there is abundant evidence of history repeating reliably in natural science. Scientists like Galileo Galei and Robert Boyle provided the history of their experimental results on the behavior of falling bodies and gases under compression. Others repeated their experiments successfully and their findings helped establish the sciences of physics and chemistry that have made innumerable successful predictions since then.

Charles Darwin made careful observations on the differences between different species of animals and proposed his theory of evolution. Paleontologists investigating the natural history of species found much historical support for Darwin’s idea. A mathematical theory combining Darwin’s basic mechanism with Mendelian genetics emerged in 1930’s helped establish evolution as a confirmed theory. Decades later, the explicit genetic mechanism of heredity began to be understood, establishing the theory of evolution as scientific fact.

The success of observational, historical sciences like evolution or astronomy suggests that one can learn from history, if it is done correctly. Santayana wasn’t wrong per se, but it is no easy thing to determine which piece of history is truly relevant to today, much less to derive the correct lessons. One way to get around this limitation is to look for empirical patterns in history to identify historical periods potentially relevant to today. What Roman and many others do is look for qualitative patterns to identify potentially relevant periods. Here they are interpreting history as to its relevance and what lesson that history teaches. The very fact that Roman says that the conventional wisdom on Munich is wrong shows that the qualitative method fails to derive a reproducible lesson from the same piece of history. Nonreproducible results are failure in both science and historical analogy.

One can argue that this failure comes from the use of qualitative methods, which are subject to bias. Those who advanced the interpretation of Munich as a mistake support a policy of intervention in Ukraine, while those like Roman, who interpret Munich as wise policy, support giving Putin what he wants to end the bloodshed. In this case, what history is teaching is what the interpreter wants to be true, instead of what is true. Historical analysis in this vein seems useless.

A possible way to improve such takes would be to employ an objective method for selecting periods of history relevant to today. Back in the mid-1990’s, I was engaged with figuring out how to invest our savings. I read some books and learned some stock market history. Being an engineer, I toyed with a simple stock market model idea I had gotten from reading Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor. I came up with a stock market valuation tool I would later call P/R. Using P/R, cycles in the stock market were evident. Plenty of other financial writers have long noted these cycles, so there was independent confirmation of what I had seen. I later learned about a cycle in prices first described by the Russian economist N.D. Kondratieff and named for him. The up and down trends of the Kondratieff price cycles corresponded with my stock market cycle (see Table 2 here).

The price cycles stopped happening after 1932 and a long period of near-constant rising price began. I found that a quantity of money type analysis could account for the broad movements of the price index and used this analysis to detrend the price data to obtain a trendless depiction of the Kondratieff price cycle. Up until 2014, the two-century relation between the Kondratieffs and stock market cycles held.

I had read Harry Dent’s The Great Boom Ahead in which he introduced the concept of the innovation wave, which I discuss here. I came up with a formulation of his innovation wave in which these happen at Kondratieff intervals. Political scientist George Modelski also has a version of sequential Kondratieff-connected innovation waves that he calls leading sectors and relates to cycles of international politics. Modelski’s Kondratieffs, so again what I was seeing had independent confirmation. I now had a system of nested price and stock market cycles aligned with innovation waves that defined an empirically-backed historical economic cycle.

Dent had interwoven Strauss and Howe’s generational cycles into his innovation wave ideas. I was intrigued the concept of a historical cycle driven by the psychological characteristics of people born at different times in history. Their cycle was of the qualitative interpretation sort which, as I noted earlier, does not provide reliable results. I noted numerous correspondences between their cycle dating and that of the historical cycles I had been working with and set about finding empirical data to support their cycle, achieving some success in synthesizing a union of my economic cycles and their generational cycle.

Having come up with an historical cycle with a significant amount of empirical support I had developed my WAG into a SWAG. The next step was hypothesis formation, in which I made explicit predictions based on analogies to periods corresponding to the same point in the cycle as the present. I then waited to see if they came true. Some did, such as the beginning of a long period of poor stock market performance (secular bear market) in 2000 and the appearance of a “fall from plateau” event associated with the 2000 secular bull market peak, “cycle-analogous” to those that had begun in 1929 and 1873, that corresponded to secular bull market peaks in 1929 and 1881. Another predicted thing that happened was the beginning of a Schlesinger liberal era following the 1980-2000 conservative era.

Other predictions failed: that the War on Terror would be of short duration, that Democrats would either win in 2016, or failing that, win in 2020, 2024 and 2028 and finally that the secular bear market would last to around 2020. The predictions had the accuracy of coin flips. In particular, the strong stock market performance after 2014, establishing the secular bear market trough in 2009, means the connection between the stock market cycle and the Kondratieffs was broken. Not only that, but the expectation of an aligned Fourth Turning over 2001-2020 has also not come true, invalidating the generational aspect of the historical cycle.

Why did predictions made based on empirically validated cycles fail? The underlying assumption one makes when using historical cycle analogy is that there is some poorly understood phenomenon that persists over time which causes these cycles to happen. Thus, when we are at the corresponding point in the cycle as in a previous cycle, the underlying phenomenon is again present and so will cause the same outcome as it did before. That this causal phenomenon or mechanism is unknown means it is not possible to know if it is still operative. This means predictions made with even a well characterized cycle (solving the problem of choosing the right period for analogy to the present) can still be wrong.

The key to making good predictions is having a valid theory or model of the historical process under consideration. I lacked such models for the various cycles making up the cyclical historical paradigm I tried to develop twenty years ago. With the final nail in the coffin for my old cycles model pounded into place in 2014, I sought a new concept to build upon for my historical-cycles hobby. That concept is cliodynamics, the study of historical dynamics, which is about developing models to describe how history progresses. One of the key processes for historical progression is cultural evolution. Both have mathematical theories and a considerable amount of empirical backing. This seems like a better place to look for insights.

Some readers might be hitting the comments to exclaim “it’s a fool’s errand to try to predict the future”. After all, as the Goatfury writes, predictions are hard! But not always. NASA routinely sends space probes to rendezvous with planets or even asteroids, which means directing the spacecraft to go not to where the target is, but to where it will be months or years in the future. That is, predicting the future to an uncanny sense of accuracy is straightforward, provided you have a good model.

And so I now write about our current crisis. That this crisis was coming was predicted in the old model I used to work with (except the timing was wrong). Crisis is also predicted by the new secular cycle model. This model is different in that it does not provide timing; forecasted turning points happen when they do, but when exactly that may be is not indicated. It defines boundary conditions within which the future trajectory of history will remain, which if violated will invalidate the model. So, it is testable.

Cliodynamics provides a mathematical description for a cycle whose length matches with Kondratieff and generational cycles. The social contagion model predicts periodic outbreaks of sociopolitical and cultural instability. Samuel Huntington, who coined the term creedal passion period (CPP) noted these episodes and forecast the next one to begin in 2020’s. The social contagion model, fit to three centuries of data, provides a more precise prediction of 2013-2027. That we are in a time of radical ideas and violence (mass shootings) has been noted by many. These CPPs track with 10 of 13 of Strauss and Howe “social moment” turnings, showing that Strauss and Howe’s qualitative assessment of historical saw a dynamic similar to the one Huntington identified which can be represented by a rather simple model. As for testing the model, it predicts a peak around 2019-20. Initial data suggest this may have come true, but we will need to wait for several more years to be sure.

The American crisis that this Substack is about refers to the third phase of the secular cycle. This cycle is one of state/societal rise and fall as measured by the political stress indicator (PSI) which is given by a math model. PSI is a measure of state strength. The state is strong when PSI is low and weak when PSI is high. The crisis phase is the period when PSI is high and rising towards its peak value. It ends when the consequences of high PSI manifest in some series of events that serve to end the rise and begin a decline in PSI. Historically this has been many different things: civil wars, state collapse, financial panic, pandemic, invasion, etc. It could be any of these or something else.

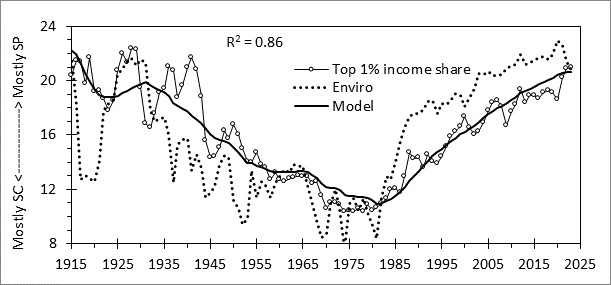

PSI is a lagged function of income inequality. I have developed a cultural evolutionary model to describe the trajectory of inequality as a function of labor power (strike frequency), top tax rate and corporate interest rates that is shown in Figure 1. These factors define the economic environment, which is denoted by the dotted line. The cultural evolutionary process serves to drive the business culture, denoted by the solid line, towards the value where it is fully adapted to the environment. I use income inequality (open symbols in Figure 1) as a proxy for business/economic culture (see left axis label in figure). I fit the model to the inequality data to obtain the model parameters, and so this cultural model is also a model for the path of inequality over time. The model output, when plugged into the definition of PSI gives how economic policy can affect the value of PSI. This suggests things like civil war can be averted by simply employing the right set of policies to bring down inequality and PSI.

Figure 1. Income inequality as a function of tax, interest rate, and strike frequency

A key factor in PSI is elite number, which itself is affected by economic inequality in a process called elite proliferation. The effect of inequality on elite number is a natural economic process that happens peacefully. Elite number can be affected in other ways. For example, excess elites can simply be killed, as happened at the Battle of Towton during the Wars of the Roses resolution of the Plantagenet secular cycle crisis. Or they can be stripped of their elite status: emancipation of American slaves meant the loss of some 60% of former slaveowner wealth, resulting loss of elite status and bringing about a long-term decline in PSI.

Because the secular cycle, unlike the CPPs, does not provide explicit timing, developing explicit predictions has not been possible so far, making hypothesis testing impossible. This means the cliodynamic-cultural evolutionary work I discuss here remain a SWAG for the present, and not advance to the level of a scientific theory.