WAGs, SWAGs and the beginning of theory development

How sense-making proceeds from speculation to true knowledge

This post is about theory development in sense-making about current events. The sense-maker typically employs some framework or paradigm to make a conjecture about an issue, which I call a wild ass guess (WAG). The term emphasizes the spontaneous and unstructured nature of the idea creation process and that it lacks any quality control (self-censorship).

Given a WAG the next step is to check the logical implications of the WAG against observations to see if it can explain the facts. One also looks for more examples of things explained by, or at least consistent with the WAG. Here is where the quality control comes in. If the WAG you pulled out of your ass doesn’t clean up nicely to pass these “smell tests” you should discard it. If it passes, it becomes a SWAG, or scientific wild ass guess, which one might also call a proto theory. In the ordinary vernacular, when someone says they have a theory about something this is usually a WAG, or if they have lots of good evidence for it, a SWAG.

A non-scientific example of the process might be the stories presented by TV police procedurals. These depict a progression from a police investigation to determine the perpetrator of a crime, to a theory of the crime used for the prosecutor’s case, and on to a jury conviction. The detective may come up with and reject several WAGs as they gather evidence before assembling a sufficient amount for a prosecutor to build a case. This is the process of SWAG formation where an explanation (case) is developed that the prosecutor believes will convince a jury. When it does, the SWAG is established. Here the SWAG is actually an LWAG or legitimate wild ass guess since the law is a not scientific, but rather a fundamentally different way of knowing than science—but the basic process is analogous.

The more evidence for a SWAG that has been assembled the more scientific it becomes and the more it resembles an actual scientific theory. But it does not become a scientific theory until it has gone through two more steps. The first is the formation of a hypothesis. A hypothesis is created by the use of a well-developed SWAG to make specific predictions of events that should happen given certain initial conditions, or as the result of proposed experiments.

The final step is to see if the predicted events occur or perform the proposed experiments to see if the predicted results happen. If they do, and this is confirmed, then the hypothesis is promoted to scientific theory. If they do not the hypothesis is rejected. The SWAG is then modified to take this new piece of evidence into account, a new hypothesis generated, if possible, and the confirmation process repeated. This may be repeated multiple times until a hypothesis from a version of the SWAG passes the confirmation step, or no further hypotheses can be generated from the SWAG and it is gradually abandoned as a fruitless path.

Even after a hypothesis becomes a scientific theory, further tests of predictions made using it can result in the rejection of the theory, or parts of it, sending some or all of the theory back to the SWAG state for an upgrade. On the other hand, a theory can keep on passing tests until it becomes a reliable workhorse that people use without question. At this point the theory becomes scientific fact. A humorous example of this comes from a scene in the movie Commando where Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character tells a bad guy that the most important thing is his life is gravity. Here Arnold is referring to a theory involving warped spacetime as a factual thing because the theory of gravity does such a good job of representing the behavior of everyday reality you can safely treat it as fact.

As an example of this process let’s consider a social science WAG proposed by Richard Hanania:

In the 1960s, Lyndon Johnson signed a series of historic bills to address poverty, racism, and the legacy of slavery. This was soon followed by an explosion in crime and dysfunction with no parallel in American history… (economist) Roland Fryer noted that until the early 1970s there was still a great deal of overlap among names given to black and white newborns in California. Since then, there has been a massive divergence…Moreover, the person most likely to give their child a black name was “an unmarried, low-income, undereducated teenage mother from a black neighborhood who has a distinctively black name herself.” Unsurprisingly, such kids have pretty bad life outcomes. Given that distinctly black naming practices rose at about roughly the same time as the explosion in crime and illegitimacy concentrated in the same communities, there’s a strong case to be made that all these phenomena are the result of what scholars have called the rise of an “oppositional culture,” that is, an active rejection of the rules and norms of mainstream American society.

Here Hanania points to a sharp rise in crime and dysfunction that began in the late 1960’s and makes a plausible argument that it is related to the rise of an oppositional culture. His evidence consists of the correspondence in time between rising levels of crime and dysfunction and a rising frequency of black parents giving their children “black” names, that is, names that are not the same as the names previous generations of black parents (or white parents) chose for their children. Hanania suggests a source for oppositional culture: “Starting in the 1960s, elite institutions started to encourage black communities to take a hostile attitude towards mainstream American society.”

Which institutions is not mentioned, but I would guess he means academia, and in the late 1960’s, these would be elite white institutions. I find it curious that black people inclined to reject white cultural attributes (as part of oppositional culture) would readily accept cultural memes coming from white institutions.

Around 1990 my girlfriend (now wife) had a couple of black teenage foster kids. Like many young people, they had a vocabulary of fresh slang words they used. They noted that when I used one of these terms, it became instantly stale, whereas my wife could use them without this happening. I found that my power of conferring instant staleness on any fresh expression, was directly related to my degree of whiteness (my wife, who is also white, apparently lacked the requisite degree). This was confirmed by a couple of black colleagues. So, I took it as an empirical observation that I had the power of conferring instant staleness, and that this power derived from my whiteness. Now one would expect universities in the late 1960’s to be full of white people like me. Hanania is arguing that these people’s stale ideas were somehow being received as fresh? I don’t buy it.

I think it more likely the naming practice was a meme acquired via prestige bias from someone like the activist Malcolm Little, who replaced his birth surname with the letter X. The idea was the surname assigned to him at birth was the family name of the white man who had owned his paternal ancestors. It was not the name of his ancestral family, which had been lost, hence his use of X, signifying an unknown. In the cultural transmission from Malcolm X to black parents the name change was applied to first names rather than surnames, but the idea would be the same.

Ta Neishi Coates identifies a strain of black populist conservatism extending from Booker T. Washington, through Marcus Garvey to Malcolm X, which had a distinct race separatist, “don’t trust the white man” vibe. The rise of black names and other oppositional behavior is a plausible manifestation of this strain of thinking, which is very different from the liberal, assimilationist message promulgated by such figures as W. E. B. DuBois, Martin Luther King, or Barrack Obama. The idea that oppositional culture came from conservative populist elements of black thought makes more sense than it came from white leftists. But black conservative populism goes back to Reconstruction, it was not a new thing in the late 1960’s and so does not explain the timing of the culture’s appearance.

When one is working with a kind of culture as an explanatory variable, one needs to have some sort of measure in mind, which can used to detect the presence of this culture and track its prevalence over time. With such a measure, causative models explaining crime and dysfunctional behavior as a function of the culture can be proposed and investigated. For example, I use income inequality as a proxy for the relative amounts of shareholder vs stakeholder varieties in economic/business culture and use this measure to develop a causal model. The model (the black line in the cited figure) then provides the measure of the culture. Hanania provides no such measure, leaving us with the rise in crime and frequency of black names as oppositional culture metrics, in the same way that a variety of metrics could be used to track the rise of shareholder culture rather than the model. These things are suspected of being related to the culture, making them potentially suitable as proxies for measuring a slippery thing like a culture. If we substitute rising levels of crime as a measurable proxy for oppositional culture, Hanania’s assertion becomes tautological: these phenomena (rising crime) are the result of…rising levels of crime.

Hanania’s argument is an example of “hand-waving.” On first glance, it seems like he is saying something, but on further examination there is nothing there. Nevertheless, there was the sharp rise in the levels of crime and other deviant behavior in the late 1960’s and 1970’s, which must have had some cause. If it is not oppositional culture derived from liberal institutions, then what is it? Hanania notes that liberals have their own explanation for this, as the effects of past or present racism, which is also a hand waving argument.

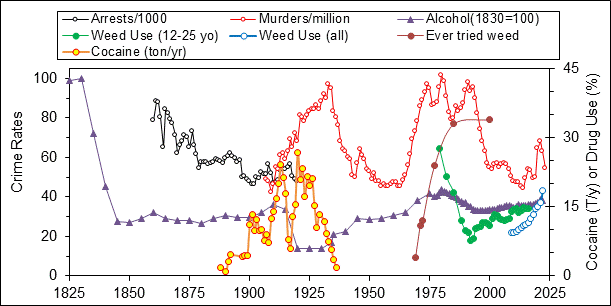

To get a handle on what was going on with crime and deviant behavior in the late sixties, it is useful to have some context, rather than treat it is isolation, as Hanania did with his description of the phenomenon as “an explosion in crime and dysfunction with no parallel in American history.” How does he know there has been no parallel? To this end I assembled some data on rates of American crime and drug use, some of which I collected in the past for previous work and some I added from web searches for this post. These include two measures of crime: arrest rates per 1000 for 23 American cities over 1860-1920 and homicide rates since 1907. I collected three measures of marijuana use. These were frequency of marijuana use by young people over 1979-2016, use frequency for the whole population since 2009 and poll data asking people if they had ever used marijuana. I also found data on legal cocaine exports from Peru, Bolivia and Java spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Finally, I had data on alcohol use I had collected a quarter century ago, which I augmented with some more recent data. Figure 1 plots all these data series.

Figure 1. Measures of crime and recreational drug use over time.

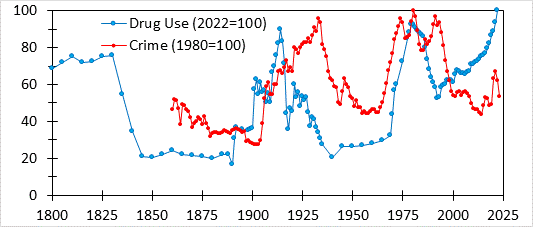

Next, I constructed a single “crime index” using the two crime measures and a “drug use index” using the three measures of marijuana use, cocaine production, and alcohol use. These are presented in Figure 2 in terms of their values relative to the peak value. One should not read this as providing an absolute measure of antisocial behavior, but rather an idea of the direction of trends at various times. In other words, it is not possible to assess whether the levels of drug use in the 1970’s were greater than those in the early 20th century or those now, but we can say that they were rising at these times and not at other times.

Figure 2. Crime and Drug use indices over time

I used Figure 2 to identify periods when crime and drug use were rising and compared them to creedal passion periods (CPP) when sociopolitical and cultural instability were rising. Table 1 presents CPPs identified by the social contagion model and compares them to the two measures of instability and the two measures of antisocial behavior. There is some correspondence that suggests periods of rising social unrest and cultural ferment tend to be associated with periods of rising deviant behavior. It makes sense to me that times when people are “acting out” politically and embracing radical cultural ideas and practices are also times when people engage in more deviant behaviors.

Table 1. Historical periods of elevated instability and rising antisocial behavior

The cause of such periods is the elapse of time from the previous outburst of radical ideas and behaviors. This can be sensed today by anyone who was an adult in the 1990’s. Compare the political happenings today with those in the 1990’s. In 2020 we saw thousands of black and white people marching under the banner of Black Lives Matter in many cities, with violence breaking out in some. The following year saw a violent assault on the Capitol by mostly white people determined to “stop the steal.” Compare these to the peaceful “million (black) man” march under the auspices of the Nation of Islam in 1995 and the equally massive and peaceful (white) men’s rally in Washington DC organized by the Promise Keepers two years later. This shows the stark difference in behaviors seen in large gatherings during a CPP compared to other times.

There is nothing magical about CPPs. They involve memes being spread via prestige bias and work much like fads. Why they happen during CPPs and not at other times is because at other times elites who had been through the last CPP countersignal against the newfangled ideas. Consider LBGT activism in the 1990’s and today. In the earlier time the issue was gay marriage and the message was that gay people wanted to get married and settle down just like everyone else—a non-threatening assimilationist message. In today’s CPP we have grown men wearing dresses reading stories to kids and wanting to be seen as women, which is a much more confrontative approach to activism, similar to the rise of gay pride parades during the 1970’s CPP. Gay leaders who had been active during the 1970’s and had learned what worked and what did not from that experience, may have guided things differently in the 1990’s. Previous experience from half a century ago is no longer present (or maybe not seen as relevant) today. Leaders may feel they had been too timid in the past and need to push the envelope.

In the last three paragraphs I made use of Peter Turchin’s social contagion model and the cultural evolution concepts developed by scientists Peter Richerson and Robert Boyd as part of an initial effort to build a SWAG out of my wild ass guess that rising crime and deviant behavior in the 1960’s was a reflection of the ongoing CPP.

When Hanania talks about elite institutions pushing oppositional culture onto black people, he is talking about what happens in a CPP, radical ideas are put forth by holders of symbolic prestige markers (SPMs). But white academic SPMs are not going to work with uneducated black people in poor communities. People in these communities are much more likely to respond to memes spread by populists like Malcolm X, as I noted above. What is more likely is these academic memes get picked up by other academics and incorporated into the development of various critical theories (actually WAGs or SWAGs) based on race, sex or gender. Such theories would have been first proposed in the last CPP, go through a long period of development in obscurity between CPPs, and then pop out fully-formed during this CPP, which seems to be what happened.

I think the 1963-77 CPP is a good candidate for why the crime and dysfunction wave in the late 1960’s began when it did. Over the longer term, I believe the effect on wage trends of Democrats abandoning the New Deal played an important role in sustaining the dysfunction after the CPP ended. As Figure 2 shows, drug use and (eventually) crime fell after the CPP ended, yet dysfunction in poor black communities continued. The argument (WAG) I have made is that when the New Deal Order was in effect, a man with little chance of career advancement due to below-average ability or discrimination could still provide a rising living standard to a prospective wife and family through his labor because the real wage for unskilled labor rose with economic growth. As a result, he had value on the marriage market and a route to prestige and service as a role model for the next wave of boys becoming men. Under the Neoliberal Order this is no longer true, real unskilled wages no longer rise with economic growth. Such men are losers on the marriage market and some embrace dysfunctional behaviors. This post presents a bit of alternate history speculating what might have happened with social deviance had the New Deal Order continued, allowing lower class men to retain their pride. These posts and others are efforts at cleaning off my WAG to see if a SWAG can be produced from it.

Sorry for all of the typos, but I’m sure you get my drift . . .

Mike, I have been following you for about 6 months and am constantly chagrined that more people aren’t doing so. I might have to do (a WAG) with the fact that you don’t engage with other theories and public intellectuals on Substack’s. Like, for instance, Matt Yglesias, who is a major public intellectual with pubic intellectual with major cred in elite political/policy circles (MPIWMCIEPPC). (I assume you will take that in the spirit I in which it is preferred.) Making comments on their posts and/or restocking them with your own comments would quickly multiply the number of people out here who know you exist and who will be able to see that you have a terrific set of concepts and ideas to engage with. Your work/thinking deserves a much wider audience!