My previous post described how SC culture (and the New Deal Order that sustained it) evolved into SP culture (and the associated Neoliberal Order) in terms of economic policy. That analysis presented this policy as an external factor that shaped the economic environment in which the evolution took place. But the political order itself is a cultural construct that evolves in response to the political environment. This environment is affected by economic culture making political and economic evolution interdependent, which complicates the story. This post will deal with the political side of what was actually a process of politico-economic co-evolution.

Before proceeding I need to introduce a framework in which I will be working. This is the presidential political time model developed by political scientist Steven Skowronek. Skowronek sees a cycle of alternating Democratic and Republican political regimes. Each regime is founded by a Reconstructive president and ends with a Disjunctive president from the same party. In between come Articulative presidents from the dominant party and Preemptive ones from the opposition. A Reconstructive president comes to power when the old regime is perceived to have failed, allowing the new president to make radical changes that establish a new political paradigm biased toward his party, or dispensation. Reconstructive presidents were historically important presidents such as Lincoln, FDR, or Reagan. They are followed by a series of presidents from their own party who articulate the dispensation. Dispersed among them are “Preemptive” presidents from the opposing party who seek to express the dispensation in ways more conducive their party’s interests. As the dispensation ages it becomes less able to address new problems as they arise and the dominant party has less and less to offer voters.

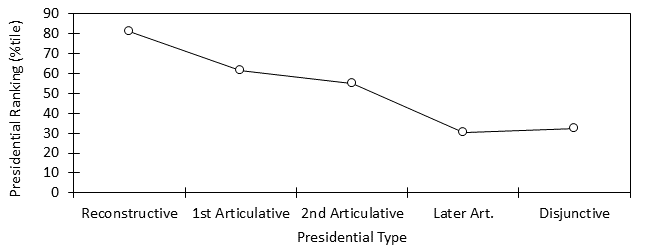

To show this I obtained consensus rankings of “greatness” for all the presidents from 22 polls of historians conducted from 1948 to 2021. For each poll, the consensus ranking of the historians was converted into percentile terms. The results from the individual polls were averaged together to obtain a broad historical consensus of “greatness” for each president. The values obtained in this way were used to obtain an average rating for each of the Skowronek types. There are more articulative and preemptive presidents than the other kinds, and so they were further characterized by the order in which they appeared. Figure 1 shows a statistically-significant declining trend for the presidents of the dominant party as the cycle progresses. It is unlikely this trend reflects qualities of the individuals themselves (or the electorates who elected them president). Rather it reflects the increasing difficulty the reigning dispensation has with dealing with the problems of the nation. At some point it gets so bad that an articulative president loses reelection to what ends up becoming a new Reconstructive president. The loser is the Disjunctive president.

Figure 1. Average presidential ranking by type in the political time model

The current dispensation is Republican, established by the most recent Reconstructive president, Ronald Reagan. GHW Bush was the first Articulative president and his son the second. A good example of how a dispensation ages comes from a comparison of the second Bush with Reagan. Both ran on and implemented two rounds of tax cuts on the wealthy, resulting in large deficits, asset bubbles and subsequent stock market crashes. This policy gave Reagan the “Seven Fat Years”, while Bush got the 2008 Financial Crisis and the Great Recession. Similarly, FDR’s New Deal got him reelected three times, while Johnson chose to not even attempt reelection. It is not surprising that late-cycle would-be Articulative presidents attempt to shift the dispensation in a new direction to try to update it to a new conditions. When successful (e.g. McKinley-Roosevelt) they can rejuvenate the dispensation, allowing their party to remain dominant. When unsuccessful (e.g. Hoover, Carter), they become Disjunctive and are followed by a new Reconstructive president. President Trump tried to transform the Republican dispensation from Reaganomics into MAGA, and lost reelection. It remains to be seen whether Biden is a Reconstructive and Trump a Disjunctive. To do so, Democrats must, at a minimum, win both the 2024 and 2028 elections.

The first Preemptive president, the first from his party since the discredited Disjunctive, acknowledges the new dispensation in order to distance himself from the old regime. For example, Bill Clinton, the first preemptive after Reagan, did not attempt to reverse the Reagan Revolution, instead making it work better for ordinary people. Declaring “the era of big government is over,” Clinton’s strategy was to get the budget under control so as to allow for interest rates to fall, and was successful in producing both economic and wage growth. Similarly, first pre-emptive president Dwight Eisenhower made no attempt to undo the New Deal, keeping very high tax rates on high-income households and generating strong economic and wage growth.

With this framework, we can interpret the fall of the neoliberal order as an example of the decay of the Roosevelt dispensation, with the Kennedy-Johnson administrations analogous to the second Bush administration in that both played a second Articulative role. Both followed a first Preemptive president who had successfully ruled in accordance with their own interpretation of the dominant party’s dispensation. Eisenhower saw the peak effectiveness of the New Deal Order, with strong growth, a low NAIRU, and the peak in Labor power. After accepting that the big government created by the New Dealers was here to stay, he preempted Democratic big government by directing it towards the creation of a military-industrial complex (MIC) that consumed over half of Federal expenditures that primarily benefitted Republican constituencies.

But these economic developments had their own impact on the environment in which political culture evolves. The economic policy created by New Deal politicians over 1933-45 not only generation a new economic culture (and associated economic reality), but also changed the voting behavior defining the political environment. Civilian employees of the Federal government increased from 1.1% of the workforce in 1933 to 1.8% in 1940 and 2.7% in 1947. After WW II, a great many people started to become indirectly employed by the government. Using Federal expenditures as a proxy for total effective employment by the government, effective employment rose from 3.2% in 1948 to about 10% in 1970. Many of the jobs created were for college-educated professionals. Professionals had traditionally voted Republican, like the small businessmen who formed the core of the Republican party. Growth in the size of the government (and effective employment) since WW II had created an environment that selected for political support for Big Government (which was coded Democratic then as now) amongst educated people. Figure 2 shows a plot (in red) of the fraction of noncollege-educated (working class) voters who voted Democratic minus the fraction of college-educated voters who did. A long term declining trend is seen showing a shift in the political loyalties of educated workers towards Democrats (and working class voters away from) over time.

Figure 2. Trends in voting behavior for various groups

WC (working class is proxied by noncollege-educated voters

Over 1948-60, college-educated voters moved seven points toward Democrats relative to noncollege-educated voters, showing that even before the Civil Rights bill was passed, the Democratic base was becoming less centered on the working class. Since the professional class was more affluent, one would expect them to benefit more from tax cuts, and with the college deferment, the Vietnam War had less of an impact on them. But the working class greatly outnumbered professionals, Democrats couldn’t afford to lose them. Hence the 1960’s Democratic administrations were also supportive of workers interests. Kennedy nominated two strong liberals to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) in his first month in office. They joined a third Democrat to give a liberal majority through the rest of the 1960’s, which had beneficial effects on labor power, as well as oversee a strong economy with good wage growth. Working class support for Democrats rose during the Kennedy-Johnson administrations.

Another trend shown in Figure 2 is a shift of white relative to nonwhite voters from neutral towards Democrats before the 1965 Voter Rights Law to increasingly favorably-disposed towards Republicans afterward. A shift of black voters towards Democrats was one factor behind this development. Another was a strongly negative reaction of racist whites to the 1964 Civil Rights law. In the four presidential elections over 1948-1960, Southerners voted an average of 8.5 points more Democratic than Northerners. For the 1964-1972 elections, they voted 7.5 points less Democratic, for a 16-point swing. The combination of these two trends implies that Democrats had lost the support of white working-class voters by the early 1970’s, and that they would be best served by pursuing policies that appealed to other constituencies. A third trend shown in Figure 2 appeared as a result of the 1960’s civil rights laws. Prior to 1964, women voters had been less supportive of Democrats than men. The Civil Rights laws created a very different socio-economic environment for women, giving rise to a 10-point shift towards Democrats relative to men over eight years.

The changes in the political environment signified by these last two trends selected for a Democratic ideology intended to appeal to minority groups and women who shared a history of past or present discrimination, that is sometimes called “identity politics.” Policies promoted as part of identity politics were a natural extension of 1960’s civil rights legislation. Republicans developed their own version of identity politics intended to appeal to white people discomfited by all the social changes following the success of the civil rights movement. Some of these were designed to appeal to people with racist views, others to conservative Christians. A fuller description of the political evolution that was ongoing with the economic one is discussed in more detail in chapter 5 of America in Crisis.

The decline in the Democratic dispensation reflected changes in voting behavior resulting from two phenomenon. One was the end of wage growth and rising inflation after 1973, which served to discredit Keynesian economics associated with the Democratic party and reduced public support for unions, weakening working class support for Democrats based on economics. The other was changes in party preferences along class, race and gender lines that arose from the growth in the size of government and Civil Rights legislation. The three trend lines in Figure 1 intersected neutrality over the 1960 to 1980 period, after which Democrats had no longer had the allegiance of the working class, and had become seen (at least by Republicans) as the party of women and people of color. The establishment of the centrist Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) in 1985 might be seen as an acknowledgement of this fact. The DLC sought to promote a mixture of center-right economic policy and progressive social policies.

The Republicans were undergoing their own evolution in response to these same forces. In the wake of Nixon’s conversion to Keynesianism to justify his choice to run deficits (with price controls), a new “supply-side” doctrine arose that claimed that one can cut taxes and inflation magically won’t be a problem, a notion that struck 1980 Republican candidate George Bush as “voodoo economics.” As previously described, by the time Republicans tried out their new notion, Volcker’s deflationary high unemployment policy offset the inflationary effect of deficits. Given the high unemployment and lack of wage growth during the Reagan presidency, Republicans would likely be vulnerable in 1988. The WC minus college-educated Democratic vote share measure in Figure 2 shows a shift toward Democrats in 1988 from 1980 and 1984, suggesting this was so. It also seems Republican racist appeals like the infamous “Willie Horton” ad, did not have the desired effect. The swing away from Democrats among whites was less in 1988 that it had been in 1980 and 1984. These facts suggested the DLC strategy for the Democrats was working, which seemed confirmed by Clinton’s victory in the next presidential election. Real median incomes for black and white men rose by 36% and 19%, respectively, during the Clinton administration, compared to actual declines over the Reagan-Bush administrations. Clinton was making Reaganomics work better for regular people than Reagan had.

In the 1980 presidential campaign Ronald Reagan described the Republican party as a “three legged stool” which remained upright (politically potent) with the support of its legs (factions): Economic conservatives (Business and free-market capitalists), Neocons, and Traditional Conservatives. The first of these had been a core consistency of the Republican party from its inception, the second were the product of Eisenhower’s establishment of the MIC, anti-Communist supporters of a big Defense budgets. The last was a mix of the “Old Right” and evangelical Christians who Republican activists had been able to convince should vote for Reagan rather than fellow evangelical Jimmy Carter. The Old Right were the remnants of the Republican opponents to the New Deal led by “Mr. Conservative” Senator Robert A Taft, who had lost out to Eisenhower in the 1952 primary campaign. The social conservatives were a combination of former Southern Democrats driven into the GOP because of their opposition to integration and conservative Christians who had previously eschewed politics as ungodly.

This third leg of the stool consisted of a defeated faction and party newcomers, so their interests were lowest in priority. The Reagan administration focused on the goals of the first leg in domestic policy and the second in foreign policy. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Neocons were eager to act, beyond the Gulf War, but the Clinton victories in 1992 and 1996 prevented further action. The economic success achieved by Clinton made Republican economic offerings unappealing to working class voters. Figure 2 shows Clinton drew working class support similar to twenty years previously, showing the damage wrought by Carter’s economic problems was gone. With the retirement of conservative Southern Democratic Legislature members in the 1990’s, their voters became Republican voters, which probably explains some of the strong shift of whites away from and nonwhites towards Democrats during the Clinton presidency (see Figure 2).

With Reaganomics no longer potent in 2000, Republicans tried a direct appeal to their third faction by selecting an evangelical Christian as their standard bearer, who won the presidency by a hair. The 911 attack gave the Neocons a chance to flex their wings, giving us the disasters of the Afghan and Iraq wars. The Bush tax cuts, made on behalf of the first leg, led to the disaster of the 2008 financial crisis. With the policies favored by two-thirds of the Republican stool refuted by the disasters they caused, the policy preferences of the third leg were the only ones left that had not been refuted by experience. The old right portion of this leg today is manifest as the Alt Right, while the Christian Right is still much the same, centered on issues of abortion and sexual morality. The rise of the MAGA Republicans and the Dodd decision overturning of Roe-v-Wade represent the last attempt for the Republican dispensation to remain relevant to American politics. Donald Trump and the Dodd decision played important roles in the poor performance of Republicans in the 2022 midterm elections, suggesting these third-faction appeals are not helping Republicans sustain their dispensation. Probably the best evidence that the Reagan dispensation is fully played out is the fact that Republicans did not even bother to issue a party platform in 2020; they literally had nothing to say on anything that matters.

What this means is according the Skowronek model, Biden is in the right location in political time to become a Reconstructive president by establishing a new Democratic dispensation. I suspect he intuitively senses this. But the last two dispensation turnovers in 1932 and 1980 occurred as the result of an economic disaster occurring on the watch of the previous dominant party president that made him Disjunctive. This was not the case for Trump, who lost more because of his personal inadequacy as a leader than to external circumstances. Hoover or Carter would have won the 2020 election handily. It was President GW Bush who had overseen multiple disasters resulting in a devasting loss for his party in 2008. Unlike Biden, President Obama inherited a crisis that gave him opportunities for bold action. A Reconstructive president would have urged his party to reject the Republican TARP proposal, allowing a larger impact of Republican financial irresponsibility to unfold while Bush was still in office, providing Obama a larger pretext for dispensation-creating action. That an astute politician like Obama did not do this (and that I fully concurred with this decision at the time) shows that it was not yet the political time for such action.

So, though the Republican dispensation has lost all relevance today, it will continue to be the wholly inadequate foundation upon which any policy must be built, until some foundational crisis arises that demands dispensation-creating action for national survival. In my next post, I present a theory proposed to govern in such situations.