Stock market paradigms

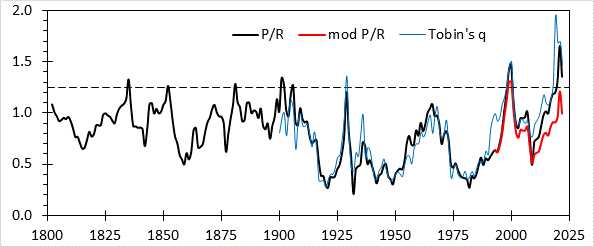

My previous post described two ways one can value a stock or index: fundamental and technical analysis. By “value” I mean determine if the asset is likely to rise or fall in price in the future. If an asset rises in price, this means it was undervalued at the time of assessment, while if it falls in price then it was undervalued. I noted that the growth in the popularity of stock buybacks and the rise of QE operations had rendered my old fundamental-based P/R index valuation tool obsolete. Figure 1 shows P/R values over more than two centuries. Up until recently, P/R showed cycles of 28-year average length that peaked around 1.2-1.3. I used this pattern to correctly predict in my book Stock Cycles that the post-1982 secular bull market was coming to an end in 2000.

The bull market did end in 2000 with a value of P/R of 1.47, which was the highest value of P/R to have been seen to that date. This value was so high it was nearly statistically different (p < 0.06) than the other peak values. The 2000 peak was widely acknowledged at the time to be a speculative bubble, so I considered this extreme value to be an anomaly and continued to believe P/R valuation was sound. P/R reached a value of 1.65 at the end of 2021, which is definitely statistically different (p < 0.02) than the previous seven cyclical market tops, including the 2000 bubble peak.

Figure 1. P/R and Tobin’s q values over time

We were either in the biggest bubble of all time or something has changed. Anyone who perused the financial media lately will have encountered dire predictions of major stock market declines made by market experts. They are not doomsayers, but rather people using fundamental rather than technical analysis. For example, fundamental analysis of Bitcoin says it is worth nothing, yet it showed a valuation of $1.28 trillion at its peak, and even after its decline in 2021-22 it is valued at hundreds of billions of dollars. It has held capitalization values above $1 billion for a decade, seemingly more than enough time for the idea that it is actually worthless to catch on.

P/R does not capture the effect of stock buybacks. If I redefine R for the modern period as cumulative earnings of all sorts rather than just retained earnings, I obtain a higher value of R, and a lower value of P/R. I did this and plotted the result in Figure 1. Prior to 1994 this modified P/R is the same as the standard one, in which only retained earnings are added onto to R, while after 2000 all of earnings are added. In between a linear interpolation between the two methods is used. The peak values for the modified P/R in 2000 and 2022 are now consistent with the past ones.

This calculation suggests that a new stock market paradigm has emerged in which much higher values of the index have become normal. The value of the stock market has become uncoupled from the economic value of the underlying companies. That shares represent a portion of a company only has practical significance in the event of a cash buyout. Otherwise, share prices rise and fall in accordance with the supply and demand dynamics of shares in a share market, while business fundamentals function as a story investors tell themselves to justify buying the stock.

The stock market has operated under other paradigms in the past. During the 19th century stocks were seen as equivalent to perpetual bonds, that is, bonds with no expiration. Such bonds were issued with a fixed interest rate based on a par value and fluctuated in price inversely with respect to prevailing interest rates. Share prices were likewise issued with a par value and priced relative to that value. Stock prices did not rise significantly during the 19th century; the market level only doubled over course of that century, compared to the 600-fold rise we have seen over the last century. The lack of price change was consistent with the belief that stocks were like bonds.

This situation changed with the beginning of the 20th century. In just six years the index rose to 50% above the highest value in the 19th century and would rise to triple that value over the next 23 years. It soon become clear that stocks were not like bonds, and prices began to be quoted in dollars rather than in terms of a par value in 1916. Investment professionals came to realize that analysis involved more than just assessing the soundness of the dividend stream, but also the potential for the growth of that stream. Discounted dividend models came into vogue, and later, discounted earnings models as the 20th century progressed. When I first started thinking about these issues back in the 1990’s we still lived in that 20th century world, which was why most savvy investors saw excessive stock prices in the late 1990’s as a bubble, although few anticipated the extent to which it would rise. Investors might get overly enthusiastic at times, but in the end, value would out. Fundamentals-based valuation tools like Tobin’s q were seen as valid (see Figure 1) and so I developed P/R based on fundamental principles But, as the modified P/R analysis in Figure 1 shows, we seem to have entered a new market paradigm with the beginning of the new century.

I first noticed something was wrong around 2014, when market action began to deviate significantly from its previous pattern. I initially believed this was just another bubble like that in the 1990’s, and tested this idea by making an explicit prediction in a June 2015 article that a major stock bear market would begin within three years. When this failed to happen in summer 2018, I considered the Stock Cycle I had written about to have been invalidated as of 2014 (P/R did not become invalid in my eyes until its rise to unprecedented levels in 2021). After 2014, I began to investigate new ways of understanding how financial and economic cycles and related phenomena operate, which led me to Peter Turchin’s work in cliodynamics and the field of cultural evolution. As detailed in chapters 2 and 3 of America in Crisis and in my capitalist crisis post, I now see American history unfolding in secular cycles driven by changes in economic culture. During the first cycle (1780-1870) and the first portion of the second cycle (1870-1942) stocks were seen as the same as bonds, the transformative effect of industrialization had not yet been appreciated. As the second cycle proceeded this potential was realized and stock prices rose. As described in chapter 2 of America in Crisis, during the first capitalist crisis (1907-1942) it gradually became clear that it was not enough for business firms to produce (economic supply), they needed to be able to sell what they made, leading to an increased policy focus on economic demand. The theoretical solution to the problem of that crisis was provided by British economist John Maynard Keynes, and the operational solution by New Dealer economic policy during WW II.

Increased taxation made possible by the 16th Amendment created the backdrop for the second stock market paradigm (indicated by the shift to larger-amplitude stock cycles in Figure 1) while the stakeholder capitalism (SC) economic culture resulting from high taxes and demand-side policy served to maintain the 20th century market paradigm. Economic policy changed during the late 1970’s and 1980’s into a “neoliberal” variety that selected for shareholder primacy (SP) economic culture as previously discussed. Under SP culture, the objective of capitalism changes from the accumulation of productive capital (the kind that employs people and grows economies) to financial capital, specifically “shareholder value.” Stock buybacks and QE, by promoting the development of higher stock market levels (i.e. the new market paradigm), are completely natural expressions of now-dominant SP culture.

Figure 2. Evolution of economic culture (proxied by income inequality) over time

This new paradigm emerged in the late 1990’s, by which time economic culture (proxied by top 1% income share in Figure 2) had become largely SP (i.e. inequality had already risen to high levels). The environment (E) creating it had rapidly appeared in the early 1980’s (see dotted line in Figure 2) in what has been called the neoliberal turn, but it took some time for the culture to evolve in response (heavy black line in Figure 2). The new stock market paradigm did not fully emerge until after the 2008 financial crisis, when stock buybacks were now consuming most of retained earnings and the Fed was actively manipulating longer-term bond prices (and, indirectly, the stock market) through QE policy.