Extension of inflation model before 1948

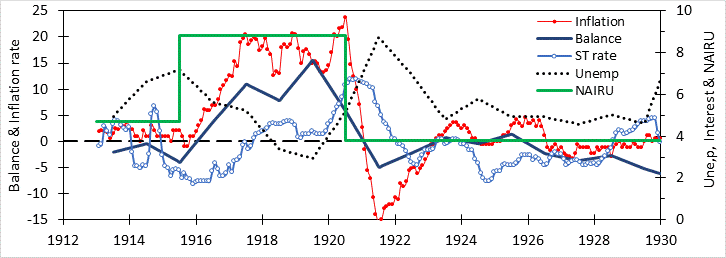

In this post, I will extend the analysis of my previous post on inflation to the period before 1948. Previously, I employed a money balance consisting of dollar inflows: money supply growth plus fiscal deficit and subtracting from them dollar outflows: trade deficit and flows into financial markets from dividends and stock buybacks. The resulting quantity is called Balance and is expressed as a percent of GDP. It is shown in the figures in this post as the thick dark blue line. My previous post showed smoothed Balance values, here I show annual values with interpolated values in between. Previously, I showed how Balance was correlated with NAIRU, providing a link between the two methods. I estimated NAIRU values for the pre-1948 period using this correlation to convert the average value of Balance over a particular period into the NAIRU for that period. These NAIRU values are shown by the thick green line. For short-term interest rates I concatenate Federal Funds rates after 1954 with t-bill rates between 1931-1954, and 1.3% less than commercial paper rates (as a proxy for risk-free rate) before 1931. These and the inflation rate are shown on a monthly basis as was done previously. Unemployment rate is also plotted, but monthly data are not available before 1947, so annual data with interpolated values in between are shown.

Figure 1. Economic data over 1913-1930

Figure 1 shows the first of these plots covering the period around WW I. The first period shown in the figure ran from 1913 to early 1915, when Balance was negative, giving rise to a low NAIRU. Unemployment was above this low NAIRU and inflation was very low as a result, averaging 1.7%. With the onset of WW I, the trade surplus doubled in 1915 and nearly tripled again in 1916. Trade surpluses represent an influx of dollars and so are inflationary. Balance rose as a result, and, starting in 1917, with the rise of inflationary fiscal deficits resulting from the entry of the US into the war, Balance rose still more, with exports and fiscal deficits peaking in 1919. The result of strongly positive Balance was to push NAIRU to levels well above unemployment rate, resulting in inflation and a wartime economic boom, reducing unemployment from about 7% to 3% by 1919.

With the war over and government spending in decline, Balance was falling. Interest rates rose about three percentage points over 1919-20, inducing a recession and driving unemployment far above the declining NAIRU, crushing inflation. Unemployment remained above NAIRU for the rest of the decade. The 1920’s bear a striking similarity to the 1980’s in that both decades began with an inflationary episode, to which policymakers responded with higher interest rates, after which inflation subsided leading to a massive bull market in stocks that ended in a crash. This similarity led some economic cycle enthusiasts to forecast that the 1990’s would be like the 1930’s. In actuality the two periods were different, the 1980’s saw high levels of Balance and a high NAIRU, meaning inflation control required very high unemployment levels, whereas the 1920’s saw low values of Balance and NAIRU under which only moderate unemployment levels gave a deflationary environment.

Prior to WW I, the US and most of the advanced countries were on the classical gold standard, under which banks adjust their interest rates in order to maintain convertibility between dollars and gold at a fixed value (the standard). Interest rates affect bank lending, which is the primary factor affecting money supply (and Balance). During wartime, budget deficits were necessary to finance the war. The gold standard would require that interest rates be raised to very high rates to maintain price stability, which would bankrupt the government. Hence the standard was suspended during wartime, and prices generally rose. Figure 2 shows patterns of inflation and debt growth during wartime and the postwar peace for 11 wars fought by Britain or America from 1689 through 1918. A pattern is evident. High inflation reflecting large increases in debt are seen during wartime. The subsequent peace sees little increase or and an actual decrease in government debt and is associated with low inflation or even deflation.

Figure 2. Inflation and government deficits during and after wars listed below:

A 1688-1697 War of the League of Augsburg

B 1701-1713 War of the Spanish Succession

C 1739-1748 War of the Austrian Succession

D 1757-1765 Seven Years War

E 1775-1784 American Revolution - UK

F 1775-1781 American Revolution -US

G 1792-1815 Napoleonic Wars - UK

H 1812-1814 War of 1812 - US

I 1861-1865 US Civil War

J 1914-1919 World War I - UK

K 1917-1919 World War I - US

Figures 1 and 2 provide strong evidence for the importance of money flows in producing inflation. The theory that arose from these observations is called the quantity theory of prices and provides the basis for the Balance concept. This idea plus the gold standard provided a set of tools for economic policy makers to manage economic affairs. Economic policymakers at these times might not think of themselves explicitly as such, but much of what was considered as politics was in fact policy. Examples include the decision on whether to have a central bank to regulate money creation, which was a hotly contested issue in 1830’s America, the decision to adhere to a gold standard rather than a fiat currency (opposed by the Greenback Party in 1874), or the 1894 Populist proposal to use silver as well as gold for money standard (bimetallism). The complaints about the gold standard were justified in that the gold standard did not produce price stability, but rather deflation, which unfairly benefited those with money to lend over those who borrowed to create the goods and services that kept civilization running. Consider how the gold standard operated in America. Over the 1870-1914 period the gold standard produced an average rate of money growth of 2.1% of GDP, which along with the fiscal surplus of 0.3%, the trade surplus of 1.2% and the average dividend payout of 5.5% gave a value of Balance of -2.5%, which corresponds to a NAIRU of 4.2%. The interest rates mandated by the gold standard were such that unemployment averaged at 5.1%, well above the NAIRU, producing 0.7% deflation. The reason why the gold standard produced deflation is because the world economy grew at a faster rate than did the gold supply. If one pegs the value of dollar to gold, then this means that economic output purchased with dollars expanded faster than did the amount of dollars, meaning fewer dollars available per unit of stuff, which requires that the price of stuff fall. The Populist proposal to use silver, whose supply was growing faster than that of gold as a standard was a way to get around this deflationary bias.

One of the reasons the Populists failed was that urban workers could not see how they could benefit from the Populist inflationary program., Unskilled wages rose only 28% in dollar terms over 1870-1914 (compare to 90% for GDPpc) because unionization was suppressed. However, in terms of what their wages could buy (that is, their living standard) they were up 65% because of the general fall in prices, including prices for the products farmers sold. The gold standard did not appear to hurt them, while what urban workers wanted, the ability to strike for higher wages, presented no benefit to farmers. Hence, the working classes were divided, allowing governing elites to make the rules in favor of those with money.

Another problem with the gold standard is it controlled inflation through positive feedback, which amplifies oscillations. When financial markets are booming, investors prefer to have dollars rather than gold in order to take advantage of rising asset prices. Gold reserves swell and banks lower interest rates to obtain more loans. Lower rates speed up economic growth, leading to lower unemployment and increased profits, further fueling the boom. Eventually, investors run out of money and the boom ends. Now there was a flow of dollars out of financial markets. Since banks were not insured at this time (and so could fail, resulting in the loss of depositor money), investors now wished to exchange their dollar profits for gold, resulting in falling gold reserves, in response to which the banks would increase interest rates and slow lending. Higher interest rates mean businesses put further expansion plans on hold. Businesses who normally manage their cash flows with lines of credit may find their line restricted or even cut off, reducing business volume or sometimes forcing it into bankruptcy, with associated job losses. Those businesses with positive cash flows would still reduce expenditures and lay off workers in order to conserve cash (if only to have the funds needed to buy the capital of failed businesses at fire sale prices). Mass layoffs and bankruptcies mean falling aggregate demand and an economic downturn. Note how use of the gold standard had banks loosening credit during business cycle expansion (making them bigger) and tightening credit during recessions (making them worse). These are positive feedbacks, which result in a less stable system. The gold standard gave an inferior kind of economic management and would be replaced by an “active policy” during the next era.

Figure 3. Economic data over 1925-1950

Figure 3 shows an extension of Figure 1 into the post-1930 era. The 1920’s showed a slightly negative Balance giving a low NAIRU with unemployment just above it. This combination produced a period of strong economic growth, but weak wage growth (real GDPpc grew by 28% over 1920-9, while real wages rose only 8%). In 1929 one of the busts typical with use of the gold standard occurred, this one starting with a stock market bubble of unprecedented size. This time the nation had a central bank who implemented negative feedback, reducing interest rates, making money available in an effort to prevent the sorts of large-scale depressions that had accompanied previous asset bubble collapses. As described in chapter 2 of America in Crisis, president Hoover also took a different approach to problem than previous administrations, exhorting industry leaders to hold off on wage cuts in an effort to preserve aggregate demand. These measures were somewhat successful in that the first two years of the downturn were slightly less devastating that the previous one in 1920-21. But in May 1931, the collapse of an Austrian bank, Creditanstalt, panicked world markets, leading the Fed to briefly raise rates to defend the gold standard. Whether or not this was the cause, the post-1929 depression did not end in two years like 1920-21 and continued on for two more years. As a result, the Republican establishment, in charge since 1921, was swept from power in the 1932 election.

The first thing the incoming administration did was do away with the gold standard. The details of this policy are given in chapter 8 of America in Crisis, here I simply note that Balance shot up and deflation was replaced with modest inflation. Inflation was modest because even though the positive Balance meant an increase in NAIRU from 3.8% to 6.3%, unemployment was so high that even after years of recovery it remained well above the NAIRU meaning inflation was not going to be a problem. Nevertheless, concern about New Deal deficits leading to inflation (as implied in Figure 2), led some to predict an inflationary crisis in 1937. The government responded to such fears, cutting spending to slash the deficit over 1937-38. This is reflected in the 1937-38 downward movement in Balance in Figure 3. The result was another deflationary downturn, which undid some of the gains achieved over the previous four years. Despite this austerity, Figure 4 shows the recovery from the Great Depression was quite similar to that following the 2008 crisis. It would seem economic policymaking has not improved in eighty years when it comes to recovering from a financial crisis.

Figure 4. Employment recovery from Great Depression compared to Great Recession

Shown is %recovered of difference between the unemployment peak and NAIRU.

The adoption of the Lend Lease program in 1941 further increased Balance, leading to a higher NAIRU of 8.8%, which was penetrated by falling unemployment during the second half of 1941, resulting in sharply rising inflation (see Figure 3). With the Pearl Harbor attack and subsequent declaration of war in December 1941, balance was set to explode, and inflation with it, as had been the case for WW I. But New Deal policymakers implemented a more “hands on” form of active policy: wage and price controls. More details on this policy are given in chapter 2 of America in Crisis, but here I would draw the reader’s attention to the gap in the NAIRU line in Figure 3 that indicates when this policy was in force. Despite enormous values of Balance, which would normally generate correspondingly enormous amounts of inflation, inflation subsided under the controls, and when the controls ended, there was a burst of inflation that went away as soon as balance fell back to near-zero levels. Note the area of the spike in Balance for WW II in Figure 3 compared to that for WW I in Figure 1. It is clearly much bigger than the one for WW I--about four times bigger--reflecting the greater length and extent of the war. Yet the CPI price index rose more over WW I than WW II: 88% over 1916-20 compared to 72% over 1940-48, despite four times more inflationary stimulus for WW II. This spectacular achievement served as confirmation of the superiority of active policy over the passive policy provided by the classical gold standard. Economic policymakers, who were now mostly technocrats trained in economics, believed it was now possible to steer the economy in such a way as to ensure price stability without the boom-bust cycles seen under the gold standard. And for a while they did until they abandoned responsible economic policy in the early 1960’s as previously described.

Figure 5. Economic data over 1950-1970

Not everything can be explained by the simple combination of Balance and NAIRU presented here. Figure 5 shows the same data as Figures 1 and 3 for the 1950-70 period, the height of the New Deal Order. With the exception of the Korean War and the late sixties, the period largely enjoyed low inflation. The 1960’s example of inflation is well explained by the rising Balance as was discussed in my previous inflation post and in chapter 4 of America in Crisis. The Korean war inflation starts out with inflation appearing around the same time as unemployment fell to NAIRU, but the sheer rise of inflation is much greater than what was seen in the late 1960’s when unemployment fell below NAIRU. The missing element is the outbreak of the Korean War. According to Wikipedia, “The first nine months of war are characterized by expansion and strong inflationary pressure due to abnormally large consumption in anticipation of possible future shortages.” This new war occurred just five years after another war in which rationing and shortages were a fact of life, and so such crisis buying would be expected. The government again imposed price controls as it had before (see gap in NAIRU line) and inflation was suppressed, as had happened for WW II. However, when controls were lifted, there was no burst of inflation, despite unemployment remaining below NAIRU. One difference was interest rates, which had been steadily rising all through the war and afterward. It is possible interest rates suppressed inflation through a mechanism different than increasing unemployment. A likely candidate for this is expectations. One big difference between the Korean War economic environment and that of WW II was that the government had been producing monthly reports on economic data on growth, inflation, unemployment and much else. Businesspersons knew what inflationary trends were in close to real time. Long before controls ended, it was evident to market participants that inflation was rapidly subsiding, and controls were being relaxed in response. By the time controls ended there was a perception that inflation was a thing of the past. Since policymakers had cooperated by keeping average Balance low (0.2 average over the war) and with interest rates rising, there was little incentive to raise prices after the end of controls. Inflation did not materialize despite unemployment rates below the NAIRU (see Figure 5). I also note that the initial burst of inflation in 1950 was itself the result of expectations of shortages coming from the war effort. The beneficial effect of postwar expectations did not last long. After the 1953-54 recession inflation reappeared when unemployment fell to NAIRU and the normal pattern was reestablished.