How my analytical approach is different. Part II

Application to the political challenge for Democrats

Democrats’ problem with the working class has deep roots

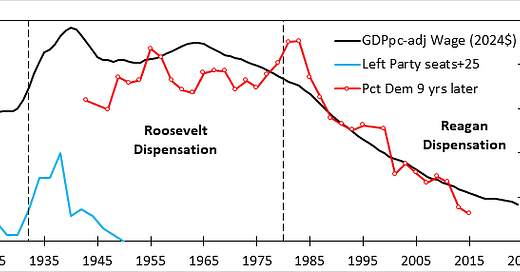

Figure 1 presents a continuation of Figure 1 from Part I of this series. As before the centerpiece is a plot of unskilled wages adjusted for rising living standards using per capita GDP (GDPpc). I note that the wage data used in Figure 1 is just money wages. About two thirds of the decline in income share received by the working and middle classes was replaced by non-monetary benefits, both public and private, which considerably lessens the material impact of trends in money wages. In any case the graph does not reflect material well-being for working people—this would be assessed using real (CPI-adjusted) wages adjusted for government and employment benefits, which can be substantial. The purpose of this wage plot is to measure changes in relative status using GDPpc, (the usual measure for how “rich” a country is) as the standard for comparison. It is an attempt at a proxy for a “sense of being left behind” among the working class.

Figure 1. GDPpc-adj. unskilled wage index and working-class Democratic House Vote 9 years later

Both indices smoothed with exponential avg. with constant of 0.6 for voting and 0.9 for income.

It is not like fast food workers fifty years ago were making the modern equivalent of $26-27 per hour. They weren’t. It is more that such working-class jobs had a higher status then. Fifty years ago, the teenaged children of upper middle-class households routinely worked jobs like this; it was considered valuable life experience. Their modern counterparts eschew such employment to pursue (often expensive) extracurricular activities to burnish their resumes for college. This sends a message that only losers do this sort of work.

Women experienced considerable discrimination in the 1970’s and before, earning only 60% what men did in 1979. This ratio has risen to 78% today, so while working class men have seen a 20% decline in real wages since 1979, real wages for working class women have not declined. Thus, it is men who have experienced the loss of working-class status wrought by the rise of SP business culture, and it is men who are increasingly dropping out of work, marriage, and family.

Strike frequency is not shown here. The reason is that strikes were essentially a form of protest in the period before the New Deal and had little effect on the wage trend. But with the backing of the New Deal Democrats, labor gained significant power. Labor actions and the threat of the same probably acted to reinforce the labor supply and demand mechanisms produced by capitalism operating under SC culture. Together, these helped transmit the benefits of economic growth to workers as well as to management and business owners, leading to the flat wage trend from the 1930’s through 1970’s in Figure 1. As I have previously described, unions were unable to contend with the imposition of high employment to suppress inflation in the late 1970’s and 1980’s leading to a collapse in strike activity. They have not been a meaningful factor since.

In place of strikes as a form or protest, I show working class support for Democrats. The voting data are for House elections. The data are plotted 9 years ahead of time. This is because Congressional incumbents rarely lose an election, meaning that voter attitudes are mostly expressed on open seats. Once elected, that initial preference is “frozen in time” for as long as the candidate holds their seat. Since the average length of prior service in the House since the late 1940’s has been about nine years, the election results plotted in Figure 1 are from 9 years in the future. While the declining trend in working-class support for Congressional Democrats actually began in the early 1990’s, the average recipient of that voting was an incumbent who had initially been elected nine years earlier. So, the figure implies the shift in working class feelings about Democrats probably happened in the early 1980’s. This is consistent with the phenomenon of “Reagan Democrats” in presidential elections at that time.

In Part I, I concluded the problems of workers proxied by the GDPpc-adjusted wage trend in the days before the 1932 critical election were addressed by the New Deal, which gave rise to the Democratic-working class coalition. Figure 1 shows that New Deal Democrats managed to maintain a relatively high level of worker status during most of the Roosevelt Dispensation. When Democrats reneged on their part of the bargain, as shown by the declining wage trend that emerged in the late 1970’s, working class voters responded some years later. Note this voting trend, like pre-New Deal leftwing politics, is more of a protest rather than a serious effort to redress their problems.

On the other hand, joining a union and strike activity did communicate the existence of a pool of voters with specific economic complaints who were available to anyone who addressed their problems. Third-party political activity demonstrated support for new ideas that could be adopted by one of the major parties. Both of these are examples of workers engaging in proactive, intelligent efforts to address their problems—they were empowering. In contrast, voting against Democrats is a passive, emotional response. As authors of a neoliberal economic policy that is inimical to working class economic interests, Republicans have continued to be the party of investors and business management, as were the Whigs before them. They could never do anything for workers without going against their core constituency.

The Republican appeal is emotional, made on cultural identitarian signaling. The subtext is “of course Republicans will do nothing for you, but neither will the other guys, at least we are upfront about it,” while the text is “we agree with your cultural values.” The most recent version of this formula is MAGA, an ethnonationalist, authoritarian1 movement under a charismatic leader whose broad appeal is a combination of theatrical displays of conservative cultural views and their expression, overlaid with working class symbolism.

I have proposed that a central driver of declining working-class support for Democrats is a manifestation of working-class dismay at their declining status as proxied by the wage trend in Figure 1. It is a conjecture supported with some evidence, what I call a SWAG. In contrast, a similar analysis I presented for the 19th century farmer’s deflationary problem in Part 1 is a theory. I showed a price series as a proxy for economic troubles for farmers, and various anti-gold parties that arose in response to this problem, none of which were effective. Here the price trend is analogous to the wage trend in Figure 1 and the anti-gold political activity is analogous to declining working class support for Democrats. The theory built around these observations predicts that were the deflationary trend to reverse, the farmers’ economic problems would end, and the need for that anti-gold parties would vanish. And this is what happened. An extraneous event outside of politics solved the deflation problem.

The corresponding prediction for the present-day working-class situation would be that if the wage trend reversed, working class voters would stop voting against Democrats. Rather they would vote for whichever party was responsible for this trend change—or at least the one in power at the time it happened. This has not yet happened, and it may not, hence my SWAG might be considered a hypothesis, awaiting confirmation or rejection.

Translation into Democratic politics

This is not a program for winning elections, the cultural changes that would produce the change in trend take far to too long. An initial election would be won due to a thermostatic reaction against Republicans. After this, policy must be enacted that enables the party to remain in power long enough for the cultural change to take home (I estimate 3-4 presidential terms). To explore this future requires consideration of who wins elections in various situations.

When I was writing my post-election take last November, I looked at the patterns of past elections. Three factors seem to determine outcomes of presidential elections. (1) Voters tend to vote against the party in power (thermostatic effect) unless this is overridden by either (2) incumbent advantage or (3) dispensation advantage. Rule 1 says if the incumbent president is unpopular at the time of the election (approval below 50%) he or his party’s candidate loses. These elections are marked in light yellow in Table 1. Rule 2 says if a popular president runs for reelection, he wins. These elections are shaded in light green. Rule 3 says if a popular president does not run, his party’s candidate will win if they hold the dispensation and lose if they do not. These elections are shaded in light blue. These rules have held for all elections since 1920, except 1948, where the polling got the election results wrong and may have mismeasured the president’s popularity as well.

Table 1. Application of the election rules to elections after 1920

Approval rates from Gallup, supplemented by Real Clear Politics for recent elections

This mechanical rule seems to leave no room for campaigning and producing a message. This is not true. The popularity of the current president in an election year is very much shaped by the messaging provided by his administration and the presidential campaign. For example, President Obama’s approval stood at 45% at the beginning of 2012, predicting defeat by Rule 1. But by October it had risen to 50%, predicting victory by Rule 2, and Obama won. From the perspective of the Rules, campaigning/messaging mostly serves to influence the popularity of the incumbent party, which is the key factor determining the result a large majority of elections, so it matters a lot.

Looking at only green or yellow elections Democrats have won half of the time since the Democratic party was established (21 of 41). Republicans have had the advantage in Rule 3 elections; Democrats have won a third of these, having held the dispensation 38% of the time.

One of the reasons Democratic voters are so frustrated with their party is they have made no effort to replace the decrepit Reagan dispensation with one of their own, so Democrats are doomed to lose elections (e.g. 2000, 2016) because Republicans have had the dispensation since 1980. On one side there are moderate Democrats and party regulars arguing Democrats should follow the example of Clinton and Obama, that is, play the politics of preemption rather than that of reconstruction. I previously explored the difference between these two options by comparing the Obama and Roosevelt administrations. Each faced the same challenge, the fall from plateau crash.

Given 2008 was a repeat of 1929 in terms of historical cycles, we had a natural experiment. Both Roosevelt and Obama used monetary policy to address the crisis. Obama was successful; Roosevelt was not—yet Obama was punished for his success while Roosevelt was rewarded for failure. Fixing the economy doesn’t help electorally. I found a big difference between the outcomes from these two administrations was the trajectory of real wages. This finding is why I have expressed my measure of working-class discontent in terms of wages. From this I propose that GDPpc-adjusted unskilled wages can serve as a proxy for society’s assessment of what an unadorned man is worth, before any augmentation by talent, advantage, or effort. When the wage line in Figure 1 is falling, a working man’s societal worth is declining, which shapes working-class political expression.

I found that the Roosevelt administration engineered an effective rise in worker wages by shortening the work week, promoting labor unions, and protecting their right to strike. According to the interpretation given by the wage trend in Figure 1, this produced a major rise in the working man’s social worth and delivered major electoral dividends in 1934, establishing a new dispensation. Obama achieved no such rise in wages, and his party was “shellacked” in both the 2010 and 2014 elections. He was an effective preemptive president like Clinton, both of whom were followed by Republicans (Rule 3) because the Reagan dispensation continued, while FDR was a reconstructive president and formed a new Democratic dispensation, where it was Republicans (in 1960) who lost the only Rule 3 election.

This line of argument assumes my favored interpretation of the wage line in Figure 1. Working class voting today may have nothing to do with economics. In this case, delivering the bacon will be unrewarded. Democratic strategy up to the present has rejected my economic interpretation of voter disenchantment with Democrats. In this case working class voters will always reject Democrats because they are too progressive. Like Republican politics, Democratic politics has been built around Red vs Blue cultural identity. As red is larger than blue, Republicans will have a permanent advantage. Democrats will never be able to achieve the progress their younger voters want because they will never gain the dispensation needed to do this.

Such a position is, of course, untenable for any major American party. Given this, if economics truly no longer matters, then the Democratic party can no longer continue in its present form. There will either be a schism or some kind of restructuring of the party. I have no idea on how this might play out. What I will do here is outline approaches that probably won’t work. One of these is modern progressivism, which combines social democracy with progressive cultural initiative. This combination is not a winner because the progressive cultural offerings have little appeal for working and middle-class conservative voters, while expensive social democratic offerings do not appeal to more affluent progressive voters who would be asked to pay for them. Such a program is a good fit for more-progressive young people who are struggling economically, but few others. As a result, it does not represent a sufficiently large constituency to win type 2 elections.

Another of these is the combination of neoliberal2 economics and progressive cultural appeals that has been the approach taken by Democrats to date. This worked for Democrats until the Obama victory in 2008, after which working class support for Democrats fell below 50% (see Figure 1, remembering to add 9 years to the dates). Since 2008 Democrats were able to win one more Rule 2 election in 2012, and this was the result of an effective campaign with a talented politician that boosted Obama’s support levels to one where they could win by Rule 2. Since then both parties have operated under Rule 1, giving a series of one term presidents from alternating parties. This pattern reflects the situation late in a dispensation, when it is no longer capable of dealing with the problems of the time and voters hate the offerings of both parties. We saw the same pattern before the 1896 establishment of a new dispensation. In fact, I believe MAGA initially was an attempt to provide an updated version of the Reagan dispensation. I also predict that it will fail (assuming we continue to have free and fair elections) because the economic policy MAGA proposes will not perform well, leading to continued Rule 1 elections.

Advocates for the status quo approach to Democratic politics are ceding Rule 3 elections to the opposition, but under MAGA there won’t be any, all their presidents will serve a single term. If Democrats govern well in the preemptive style, it is theoretically possible for them to win a first term by Rule 1, when MAGA screws up, and then win a second term by Rule 2, before losing in the next election by Rule 3. Even if this were possible, based on the first three months of Trump’s second term, it seems likely that MAGA can do more damage to the country in a single term than Democrats can undo in two terms, which means going with the status quo is untenable, a situation which others have noted.

If this won’t work either, what can be done? This will be explored in Part III.

Trump has issued 157 presidential orders over 123 days, a record rate of 1.28 per day.

Michael, I left a similar note in the chat section: In case you haven’t seen it, think this essay in The Washington Monthly provides are great deal of support for your ‘stakeholder’ capitalism thesis!

https://washingtonmonthly.com/2025/06/01/the-secret-to-reindustrializing-america-is-not-tax-cuts-and-tariffs-its-regulated-competition/

Wages are not the only thing that determines perceived status. Nationalism, identarianism, morality, and hobbies all can as well. Democrat pitch is "we will screw you, but we are better than you" while MAGA is "we will screw you, but we are the same as you". Means democrats have a more motivated donors and activist base, since they get to feel morally superior, but lost some attraction from general population voters.

I don't think your prescribed policies would accomplish what you want. A more feasible route is to improve the provisioning of status goods - for instance removing taxes on luxury, encouraging social clubs, and removing subsidies for low status industries.